Higher education has landed in a bad press cycle. The criticisms come from a variety of quarters. Republican governors exclaim that woke professors are indoctrinating American youth. Parents see astronomical price tags and read clickbait articles that make it seem like colleges prioritize rock-climbing walls over learning. In the meantime, educational entrepreneurs are busy developing credentials that people can earn online to short-circuit the degree process and launch directly into jobs. What do we need these expensive institutions for, they argue, when people can purchase the credentials they need for high-paying work?

These criticisms are filtering down to students. In 2019, two professors at the Harvard Graduate School of Education conducted a massive set of interviews with 1,000 students on 10 campuses. They summarized their findings in a report in The Chronicle of Higher Education:

In our . . . conversations with students, we found that nearly half of them miss the point of college. They don’t see value in what they are learning, nor do they understand why they take classes in different fields or read books that do not seem directly related to their major. They approach college with a “transactional” view — their overarching goal is to build a résumé with stellar grades, which they believe will help them secure a job post-college.

The study’s authors suggest that many students today — just like their parents, politicians and the public — are missing “the point” of college. But when presented in those terms, the problem raises a question that gets more complex the more you examine it. What is the point of college? Without a doubt, students enroll in institutions of higher education to get good jobs. But what else should they expect to find there?

This past spring, I posed this question to dozens of people within and outside of higher education, and — this is no exaggeration — I never received the same answer twice. Almost all were happy alumni, albeit from different institutions, and their answers took for granted that college promises something deeper than financial reward. But it was difficult to sift through those perspectives to find the point, the value proposition that justifies the sacrifices that students and families make to cover college costs. Perhaps the pandemic and inflationary pressures have intensified the doubts that many already felt about the real value of a college education.

When I was an undergraduate at Notre Dame, I took a philosophy course on Aristotle with Professor Sheila Brennan. Although reading Aristotle can be challenging — as I learned to my sorrow while trudging through the Metaphysics — much of his work rests upon careful observation of the world around him. He spent years studying sea creatures off the island of Lesbos to develop his theories about the natural world. He took the same approach with the human world. Before we decide how humans should live, he argues, let’s see what most people say, believe or do. From there we can develop our own ideas.

Brennan’s course instilled in me a lifelong devotion to this approach to tackling the questions that matter to us. Don’t start by cogitating in your study. Get outside and see what you see. On a recent visit to Notre Dame, I tried to follow Aristotle’s philosophical footsteps by putting my own feet on the ground and seeing if I could find answers to the question about higher education that plagues many of us — students, parents and the public:

What’s so great about college?

Making commitments

I stand in the middle of South Quad, Rockne Memorial Gymnasium at my back and O’Shaughnessy Hall in front of me. On this day, a cold and cloudy afternoon in March, my attention is arrested by a semicircle of plastic flowers planted in the ground. Two young men are standing in front of this fake garden, and I expect them to hand me a flier or make a pitch for a cause. But they are quiet and don’t interact with passersby unless they are approached. My curiosity gets the better of me.

“The flowers,” says one in response to my question, “are supposed to represent the babies that have been lost to abortion.” He wears a Notre Dame sweatshirt and a knitted cap.

“So, are you having a demonstration or something?”

“No,” he says. “We’re just here to make sure that people don’t steal the flowers or vandalize the display.”

“It’s like a vigil,” the other one says. He looks older, he may be a graduate student. “We’re just volunteers. I’m from the Knights of Columbus, and he’s from the pro-life group.”

My quest to discover the value of college unexpectedly starts here in the open air, where these young men are demonstrating their commitment to a cause that matters to them. I’ve participated in enough campus events to know that sticking plastic flowers into the ground and coordinating volunteers to watch them doesn’t happen without lots of time and energy. Meetings were called, group chats formed, supplies ordered and permissions from the University obtained. At the same time, another group of students was doing similar things to coordinate an opposition response.

Depending upon your position on abortion, you might feel annoyed by either group. I am intrigued by them both. They both reflect one of the reasons people often cite when it comes to the deeper value of college: helping students discover and pursue their passions. Both groups at play in this drama on the quad are driven by a sense of purpose, supporting causes that involve core human rights. These students are ready to spend hours standing in the cold or to risk the ire of campus officials for engaging in acts of vandalism or theft.

I wonder whether they would make similar sacrifices for their courses in engineering or philosophy. As a professor, my first thought about the value of a college education would focus upon the things that happen in classrooms. But I have seen again and again how students often feel and express their deepest selves in the causes, groups and extracurricular pursuits that occur when they are not studying or attending class. Student-athletes practice for several hours a day during their season, and keep their bodies fit throughout the year; student leaders politic with each other and the administration like they are taking an extra class or two.

We can oversell the idea that the extracurricular activities that students pursue spring from the depths of their souls, or that students should discover their eternal purpose in college. Once I was speaking to an advisee of mine who was on the swim team. She described the intense nature of the commitment: getting into the freezing water in the morning dark, hours of practice, workouts in the weight room.

“You must be a really competitive person,” I said.

“Not really,” she said. “I’m not here to set records. I like the fact that the team gives structure to my day, and I love the other girls on the team. I’m a better student and a happier person during swim season.”

My swimming student and the guardians of the flowers — and other students who pursue such activities on campus — don’t all pursue their extracurriculars with the same level of passion or expect to find their life’s purpose there. But they are developing a commitment muscle that will serve them well after they graduate. We can be dragged along by the river of life, or we can make and meet our commitments. Every student who arrives on a college campus has already made a substantive life commitment through the act of matriculation. If they graduate, they will see the rewards that such commitments offer to a good human life.

College campuses train that commitment muscle. It gets flexed when students choose to attend college, when they sign up for each of their classes, when they stand out in the cold to guard plastic flowers. This notion seems like a fitting start to my quest. Whatever else I might find in the buildings I visit next, it will rest upon the value of such commitments.

The individual journeys undertaken on a college campus are consequential ones that can chart a life course, but no student makes this journey alone. It unfolds in the company of friends and helpers.

Relationships that matter

I turn right and head toward Alumni Hall. I see a row of dorms that have long stood on this quad — Alumni, Dillon, Fisher, Pangborn — with South Dining Hall among them. If we consult the wisdom of happy alumni on what made college great for them, we will likely hear about the essential role that dorms, dining halls and other communal spaces played in their experiences. In these spaces we can form friendships that can last lifetimes.

My wife has a dozen college friends with whom she remains in close contact, a group of women who shared dorm rooms and apartments at Saint Mary’s College in the late 1980s and early ’90s. Thirty years after graduation they maintain a very active group chat, tailgate at football games, visit each other in different cities and coordinate support for anyone facing a life crisis. In the wake of a 2021 viral attack on my heart, when I spent two months on life support, these women were a long-distance crisis-support team. They sent food and gift cards to our family, had Masses said in my name, ordered pizzas for the nurses on my hospital floor, and called and texted my wife every day.

Although college administrators and faculty create opportunities for students to interact — orientations, dorm life, campus events, group work in classes — such powerful relationships often happen from proximity and serendipity. Students spend a lot of time in each other’s company. They might not always realize what a gift that can be. A recent article in The New York Times documented the travails of a lonely millennial to discover friends through travel. She booked a package trip with a company that promised lots of engineered socializing. She spent a small fortune to fly to Morocco to make a few new friends. I met my best friend in college by walking a dozen yards down the hallway to his dorm room.

The friendship bonds we form on a college campus have special intensity for traditional-age students, since we are still forming our characters at those times in our lives. Just as students test out career paths or interest groups, they are testing out parts of their adult personalities. Their developing characters are formed and reformed and take a new shape by the time they graduate. Many of us still feel the imprints our closest college friends made on our selves.

But the meaningful relationships we form on campus extend beyond our peers. Sean Scanlon ’91 has spent a career in fundraising and currently serves as vice president of advancement at College of the Holy Cross. We met in college through the mutual friendships among my wife’s friend group, and we now have our own three-decade long friendship. I wondered what he’s heard alumni say about what made their college experiences great.

“When major donors make a significant contribution to a university,” I asked, “what do they cite as their inspiration? Do they talk about their friendships?”

“For certain,” he responded, “they do speak fondly of the friends they made on campus, but they also point to relationships with professors or staff members who played a formative role in their personal or career development.”

At Syracuse University, where he spent seven years as vice president of development, Scanlon frequently heard a phrase that highlighted the reason why these relationships spurred alumni donations: “Someone took a chance on me.” A professor recommended a student for an internship; a resident assistant guided a student through a mental health crisis; a graduate teaching assistant invited a promising student to join a research project. With their mentorship and support, these individuals opened up new possibilities in the lives of students.

With his comments in mind, I turn my back on the dorms and the dining hall and walk across the quad to the Coleman-Morse Center, a building that houses offices dedicated to supporting students in multiple ways. I meander along its hallways and peer into offices and lounges where students are studying, working in groups, or meeting with staff. I pass Campus Ministry, the Writing Center, Academic Services for Student-Athletes and the Center for Student Support and Care. This last office has assumed a starring role as pandemic trauma and mental health crises have soared among today’s students. I see closed office doors, behind which students who might believe they can’t stand another day may be hearing from counselors who reassure them that they can. And if the students can’t stand that tomorrow when it comes, they may come back again.

I conclude my tour of Coleman-Morse in the Campus Ministry office. Palm Sunday is a few days away, and the office has sponsored an event in which students and staff were invited to wash each other’s feet in remembrance of Christ’s Passion. Posters are hung around the office, and students have expressed their feelings about this experience in brightly colored markers. A campus minister emerges, hurrying somewhere important, and sees a middle-aged man gazing around with no apparent purpose.

“Can I help you find something?” she asks me.

I wonder how many times a day she offers to help someone. I wonder how many times that offer gets extended on a college campus every day, every hour, every minute. The individual journeys undertaken on a college campus are consequential ones that can chart a life course, but no student makes this journey alone. It unfolds in the company of friends and helpers. What happens in these offices, and what can happen in dorms and dining halls, opens up possibilities that otherwise might never have appeared to us, or that appeared and we were afraid to embrace them — until someone gave us a boost.

“No, no,” I say. “I’m just looking.”

She walks out of the office briskly; I follow slowly behind.

Finding opportunities

Back out in the sunny cold I turn left, heading toward O’Shaughnessy. On my left I pass a building I never stepped into during my four years on campus: Hurley Hall and its conjoined twin, Hayes-Healy Hall. These structures spent decades as the home of business at Notre Dame until the construction of what’s now the Mendoza College of Business along DeBartolo Quad. Hurley’s foyer proclaims commerce with pride and ostentation: world maps on the walls, a massive globe in the center of the room, tiled floors and brick arches.

Capitalism long held court here, and that reminds me of the students in the Harvard study affirming that they have come to college to land high-paying jobs. Take a poll of English professors like me, and you might find that career preparation rates low on the list of things that make college great. If I could have lectured to those students in the Harvard study, I would have trotted out a slogan or two about the real purpose of college: Expand your mind! Open yourself up to new intellectual horizons! Challenge your values and beliefs!

But I’m less sure about those slogans than I used to be. A week before my trip to Notre Dame, I had lunch with Guadalupe Lozano, a mathematician from the University of Arizona who studies methods to support high school and college students in Hispanic-serving institutions. After I told her I was writing this essay, I waxed poetic about the “real purpose of college,” which was to force students to tear down and reconstruct their beliefs and value systems, and how well that described my undergraduate intellectual journey. She stopped me.

“I want to tell you a story,” she said. “In our research, I recently encountered a student with a strange first name: Fnu. I asked my team about the origin of this name. It turns out this student had emigrated from Mexico as a child, at which time he was not able to tell officials his own name. He was thus designated FNU: First Name Unknown. You tell me, Jim: Has that student come to college to have all of his values and beliefs torn down and reconstructed?”

With a little shame in my heart, I realized what Lozano was telling me: What made college great for me might not be the same for everyone. I came from a privileged background: a white young man from the suburbs, raised in a stable family with a father who was an accountant but had imposed no career expectations on me. My values and convictions withstood — but needed — challenging and expanding, and college did that for me. But the students with whom Lozano works might need very different things: safety, refuge, welcome, support. And for many of those students, college offers a path toward financial stability and out of generational poverty.

Numbers make this case. For decades, a significant gap has separated the earnings of college graduates from those of people without college degrees. Forbes magazine recently pointed to a 2021 study which reveals the gap through lifetime earnings: $2.8 million for college graduates, $1.6 million for nongraduates. U.S. Department of Education figures tell the same story: In 2020, the average annual salary of a college graduate was $59,600, compared to $36,600 for those with high school diplomas alone. If you are seeking to escape cycles of poverty or simply to create a better future for yourself and others, college can do great things for you.

As I leave Hurley, I wonder whether my quest to discover the point of college is quixotic. What makes college valuable for one student might mean nothing to another. Maybe that’s OK. Maybe what really makes college great is how it holds a collection of buildings, opportunities and people that offer many pathways to a good human life. It’s a simple but attractive idea. Maybe my quest is over. It’s starting to rain anyway. I should head back to the Morris Inn and get ready for dinner.

After a moment of hesitation, though, I decide to make one final stop.

Creating philomaths

A student holds the door for me as I enter O’Shaughnessy, the classroom building where I spent the most hours as a student double-majoring in English and philosophy. Most courses in the liberal arts were held here: history, anthropology, French, Sophomore Core. I trekked here from Grace Hall almost every day of the week throughout my four years.

I walk slowly up and down the hallways, stopping to read the posters pasted on the walls. Dozens of flyers advertise a course in Gaelic. Clubs and organizations make pitches for new members. Departments announce sponsored lectures by visiting scholars. I glance into classrooms, mostly empty now in the late afternoon. Eventually I walk to the end of the second floor near the Department of Classics. I am searching for someone, the professor who made the most difference in my educational life. But I know he’s not here. He died almost 20 years ago.

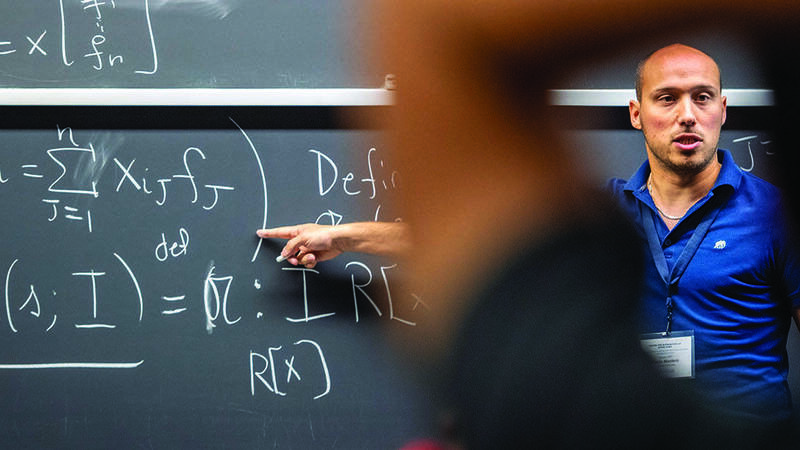

I was introduced to ancient Greek in high school, where we mastered the basics and read Homer’s Odyssey. But I really fell in love with Greek at Notre Dame. I took courses with Professor Robert Vacca, who also taught my year-long Core seminar, and we formed a good relationship. Later he wrote graduate-school recommendations for me, and I visited him when I returned to campus. He was a deeply thoughtful man who was not hesitant to pause and let ideas marinate. In class, I sensed that he actually cared about what I thought. For him education was a conversation between teacher and student — not a one-way transmission from teacher to student.

That viral attack on my heart that I mentioned? After two months in the intensive care unit, I was brought back to life by a heart transplant, but a stroke hit the language center of my brain during the long surgery. When I woke up, I had lost the ability to speak. It took many months of speech therapy, flashcards and daily practice to learn to use words again. As part of that reacquisition, I decided to push my brain a little harder and relearn a foreign tongue. Filled with fond memories of my time with Vacca, I chose ancient Greek.

I bought a textbook and a notebook and sat down every evening to do the basic work: conjugating, declining, memorizing. It didn’t take long for me to move beyond these basics and re-engage with the classical world more broadly. I read a new translation of the Odyssey. I began listening to a podcast about ancient Greece and joined a related Facebook group. Every night at 7:30, tired from the day, I was tempted to skip my evening study. By 8:30, half an hour after I had brewed my tea, my brain was on fire. I had become a learner again and was experiencing the pleasure of charging my brain with new words and new worlds.

During this second-life study of ancient Greek, I discovered a word that described what I experienced during that evening hour of study: philomathy. The roots are familiar in English: philo, which means love or friendship, and mathy, which in this context refers to learning. A philomath loves the process of learning. Most of us feel pride or satisfaction after we have learned something new; but philomaths embrace the learning work itself. They are the travelers who realize that the journey matters as much as the destination. They are the tinkerers, the explorers, the challengers, the ones who walk into a situation and think: Why do we do it like this? How else could we do it?

The habits of philomathy create good humans. Psychological research on happiness suggests that ongoing exposure to new ideas and experiences contributes to a thriving life. Gerontologists report that humans live longer when they keep challenging their brains. Scratch a major scientific discovery and you will find a human being who was addicted to learning. Employers want employees who have the capacity to be trained, retrained and retrained again as the conditions of their industries evolve. Entrepreneurs succeed when they bring their learning tools into uncertain conditions and spot opportunities.

Although very few of the people I interviewed mentioned the word “learning,” they were philomaths all. Humans are born to learn; our brains learn whether we pursue it intentionally or not. But the learning brain that animates the curiosity of a child can easily fall into disuse as we move through our adult lives. A college education provides a lifelong antidote to that terrible loss and medicine to nurture our brains back to health when they fall into complacency.

I wonder whether the bad-press cycle of higher education occurs because people expect so many different things from the college experience. Students are promised lasting friendships; some of them are lonely. Not everyone lands a good job after graduation. Parents and governors may be dismayed when young people don’t follow the paths they took. When these things happen, people question the value of what happens on a college campus.

What makes college great is learning. Colleges seek to create philomaths. When students embrace that calling, it will transform their lives. Philomaths maintain the curiosity that drives them into new commitments: championing a cause, taking up a new hobby, joining a nonprofit board. They step beyond the tiny circles of their neighborhoods or their politically like-minded friends and welcome new relationships. They find more creative approaches to their jobs, or leave those jobs for even better ones. And in their darkest hours, they might find that this love of learning, and the memory of a person who fostered it, can bring a dying heart back to life.

I have a little time left before dinner, and my first impulse is to head back to the hotel and rest. I have found an answer that satisfies me. But as I walk out the door of O’Shaughnessy, it occurs to me that I have been lingering in the familiar parts of campus, the ones I have known since I was a student. I realize the campus has expanded in mind-boggling ways since then.

I wonder what else I might find beyond South Quad.

I turn myself in a new direction and keep walking.

James Lang taught English at Assumption University for 20 years. Still based in Worcester, Massachusetts, he is an essayist and author of six books about teaching and learning, most recently Distracted: Why Students Can’t Focus and What You Can Do About It.