Professor Steven Semes’ Roman epiphany came one morning while he was watching a wall dry.

He was standing in Piazza Navona, staring at the freshly renovated church of Sant’Agnese in Agone, a Baroque landmark more than 300 years old. The scaffolding had just come down, “and the façade was still dripping wet from the restoration process, which involves a gentle wash of water for a long period,” Semes says. “I remember going up and just touching the travertine, which was so perfectly crisp.”

Even for an established architect, the sensation thrilled. “I stood in front of Borromini’s church and I said, ‘It looks like it has just been built.’”

Semes gets a similar tingle today when he sees a new building designed well on classical principles. “This is not an antiquarian exercise,” he says. “This is something that can be done. And whether the building is 500 years old or one year old doesn’t seem to matter very much.”

You could hardly distill what the School of Architecture hopes to impart through its 52-year-old Rome Studies Program better than that. The school is still the only one in the United States to require its students to go abroad, a major selling point for its rare, classically grounded curriculum. Third-year undergraduates live and learn in Rome for a full year, graduate students for a semester, a tradition that grew out of the shorter student trips that Professor Frank Montana, then head of architecture, was leading in the 1960s.

Montana was a rare talent — a classically trained modernist, an artist whose oils, watercolors and sketches still hang in Walsh Family Hall, while the sale of others has raised money for the school. His gifts delivered early professional success, and he spent much of his 20s in Europe, absorbing its vast architectural heritage along with its cuisines, arts and languages while winning prestigious honors for his own work. By age 28, in 1939, the Italian-born New Yorker was teaching at Notre Dame.

At some point he began taking his students to Rome for a taste of what he’d experienced. By September 1969 a reported 47 Notre Dame architecture and art students were living in a hotel near the Vatican. In time, their successors would be taking classes in the renovated studio space that Montana had established on the Via Monterone — a launching pad for their own European explorations and countless remarkable careers.

Much has changed since that first group sketched its way up and down Italy. Semes, who first visited as a Columbia University graduate student in 1979, remembers a city choked with traffic, its grandeur diminished by sooty walls and scrub trees growing out of ancient rooftops. Political unrest had prompted the parking of a tank in front of the Church of the Gesù — an ominous assurance of security. But the city has calmed down and cleaned up, and widespread restorations have transformed the grimy earth tones of the 1970s cityscape into the pastels a visitor would have seen in the 17th century.

The formal lessons have changed as well. While Montana wanted students to understand classical concepts, he didn’t necessarily think they should build that way. These days, Semes says, “We do teach them to design classical architecture. Not because we believe that’s the only thing you should do today, but because we think that learning how to do it, whether you decide to continue to do it or not, will make you a better architect.”

It’s said that while most of the world’s great cities feature one or two centuries’ worth of architectural marvels, Rome has 20. It’s also said the attentive visitor can learn as much from Rome’s mistakes as its masterpieces. But that layering of streets and buildings can be disorienting at first for Americans who’ve grown up around cities laid out in tidier grids. Rome’s streets by comparison are a maze of medieval unpredictability.

“The first two days were just a whirlpool” of jet lag, awe and confusion, Alexander Preudhomme ’18 recalls. Once he got his bearings, he began to think of Rome as a series of outdoor rooms, with surprises waiting around every corner. “And what that does is turn what might be a 20-minute walk into what feels like five.”

During Preudhomme’s year, the long trip on foot from the hotel where he and his classmates lived to Notre Dame’s then-new Rome Global Gateway on the Via Ostilia took them through the famous Forum, the old city’s ruined seat of government and commerce. “We were practically locals” by year’s end, Preudhomme says, “because it would always be a mad rush trying to get past all the tourists just so we could get to class. And so you really start to experience, maybe, what the Romans have to deal with on a day-to-day basis.”

Alumni often speak of moments in their Rome year when everything clicked. “It was like a super in-depth tour of the city basically every day of the week,” says Chris Lattimer ’16.

For Stephanie Jazmines ’11, now a Walt Disney Co. imagineer who grew up in Los Angeles, the click was a visit to the Insula dell’Ara Coeli, a well-preserved second-century Roman apartment block: “I started to realize that depth that could only come when you’re face to face with physical history.”

Done right, Professor Semes argues from personal experience, Rome is a city where aspiring architects connect the head and the heart, so that their own ideas might one day translate into buildings and places that people will treasure down through generations. Gregory Young ’16, now practicing in Lisbon, recalls an assignment from guest professor Michael Graves, a pioneer of the New Urbanist and postmodernist movements. “He showed us in a very visceral way how to fall in love with something as simple as a brick wall in the sun,” Young says.

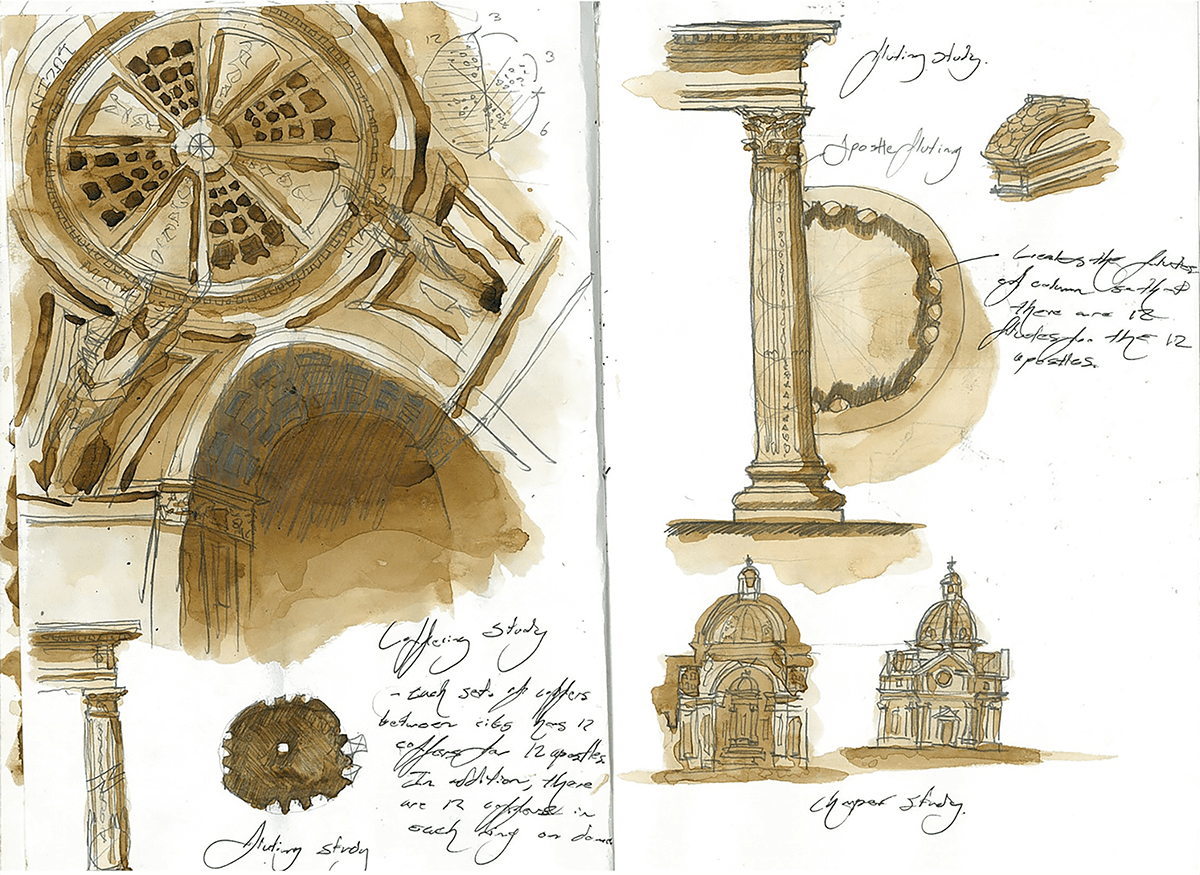

The students have taken just enough Italian by the time they arrive to fumble their way aboard a city bus or, Young adds, hinting at a memory, to order the wrong pasta. In Rome the undergrads take their next steps as novice designers and dive deeper into architectural history. The city itself, and two formal courses, introduces them to urbanism — “how to make a city,” in Semes’ definition. And everywhere they go: sketchbooks. The autumn is for freehand drawing; the spring for watercolors. It’s no less intense than what they’d learn back home, but it’s more flexible, leaving more time for Rome, for field trips around Italy, for pickup soccer games in the shadows of the Colosseum.

For life.

“It was my first time living outside of Indiana,” says Lattimer, who has worked on the restoration of Detroit’s long-abandoned, neoclassical Michigan Central Station. During a holiday he took off alone for Slovenia and Croatia. Breaking away from the American pack ended up being a more social experience than he expected. “When you’re on your own for a week,” he says, “you branch out a little more.”

In Rome, students buy their food in small shops and open-air markets, cooking in groups on rotating shifts. Early during Lattimer’s year the women let on that the men needed to pull their weight routinely, which they did. And once a month, on “Boys’ Night,” they closed the kitchen to their female counterparts entirely, cooked dinner, handwrote the invitations and served the meal to music. “Going all out with the presentation,” he says. “That was very unique to our class, but I think it brought us together as a family.”

“When they arrive, they look like they’re 18,” Semes says. “When they leave, they look like they’re 21.” And while the recent establishment of a Notre Dame dormitory — The Villa — has made life in Rome a little more like life at home, the students are still responsible for themselves in ways they’ve never been before.

For many, the year has an important faith dimension. “To be Catholic in Rome is spiritually saturating,” Jazmines says. During Lent, Preudhomme and a classmate joined seminarians who had selected 40 of the city’s oldest churches to visit for daily Mass — a way to reflect on the experiences of early Christians.

That’s what they brought home with them. Changed forever.

The coronavirus cut things short in the spring of 2020 and canceled them altogether in 2020-21. Stuck in South Bend, the disappointed students took on the same projects they would have done on site, using online resources, their imaginations and a powerful yearning to learn what they could from a distance. In May, the school announced it was sending them to Rome for the summer. As Semes says, “they will be better prepared for it than any previous class.”

If he could guide those students to a favorite spot, Preudhomme, now a San Francisco-based architect, might choose the Piazza Navona, that place where Semes had his epiphany. There, some of the world’s most beautiful buildings enclose an ancient chariot-racing ground. You can’t help but feel that ghostly movement.

“You find yourself walking up and down the whole thing. And as you’re walking, you’re experiencing the architecture, the fountains . . . the street art and the tourists, who are in equal admiration of the space. And oftentimes you’re doing that with a cup of gelato in your hand. . . . When you go across the ocean, your worldview just explodes.”

John Nagy is managing editor of this magazine.