Illustration by Keith Negley

Illustration by Keith Negley

I was scared.

I didn’t raise my hand because I had something to contribute. I certainly didn’t have answers to the professor’s questions. My hand was up in a last-ditch, Hail Mary effort to avoid embarrassing myself.

The class was an English literature survey, and I didn’t belong there. I wasn’t an English major, and I hadn’t taken the prerequisites. But the course fit my schedule, and I bluffed my way past a skeptical academic adviser, assuring her I had what it took to succeed in the course.

I didn’t. I was a first-year student in the first weeks of my first semester at the only college that accepted me. High school had been a train wreck. There was trouble at home, I flunked courses regularly, and I was contemptuous of those teachers in my all-boys Catholic high school whose idea of discipline involved smacking me around the hallways. Not that I wasn’t asking for it. I was arrogant, rarely listened in class and even more rarely studied. One day in math class — I hadn’t been paying attention, as usual — the teacher sidled up beside me and kicked me in the foot. Your problem, he said, is that you have a problem with authority. Since that was the pose I adopted each day, I guess you could say I succeeded at something.

I fancied myself a reader, though my reading was aimless. I favored novels with protagonists I admired or thought I understood: Holden Caulfield, Sal Paradise, Randle McMurphy. I thrilled at the ways they called out the hypocrites, the phonies, the suck-ups; how they refused to play the game. I had told myself I was like them, or would be when I finally got out of high school. Everything would be different when I got to college — if I could get into a college. Everything would change.

But now I was in college and nothing felt different. I wasn’t sure why I’d come to this small school I’d never heard of until I received its brochure in the mail. I didn’t know what I wanted to study, and I had zero clue about a future career. Everyone I met seemed more confident, more assured than me. They seemed happier. I talked a big game — I’ve always been good at talking — but deep down I wondered if I wasn’t the failure I half-believed I was.

And here I was over my head in an English class I shouldn’t have taken in the first place. The professor had asked us to open our Norton anthologies, an intimidating book the size of a tree stump and about as digestible, to a poem we hadn’t read before: “On First Looking Into Chapman’s Homer” by John Keats. My heart sank when I read the first few lines:

Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold,

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen;

Round many western islands have I been

Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold.

Realms of gold? Bards in fealty? Homer I sort of knew, but Apollo? And who was Chapman? None of it made sense.

That’s when I raised my hand.

“I don’t think this is the right way to teach this,” I told the professor.

The professor looked at me, not unkindly. He had bright blue eyes and blond hair, receding in front, curling over his collar in the back. Under the corduroy jacket, he had the burly shoulders and arms of a college wrestler.

“Instead of introducing the poem in class,” I said, “you should assign it in advance, so we’d be ready for it.”

It wasn’t bad pedagogical advice, but that’s not why I suggested it. I was bluffing again. I couldn’t bear another bewildering discussion of writers I hadn’t read and readings I didn’t understand. I dreaded the possibility I might be called on and my abject ignorance revealed, at last, to everyone. The professor continued looking at me.

“OK,” he finally said. “We can do that.”

I was stunned. I don’t know what I expected, but it wasn’t amiable agreement. I don’t recall what we did for the rest of the class. I just remember feeling humiliated. I was utterly transparent and had made a fool of myself. I couldn’t wait for class to end.

That night, I went to the school library for the first time. I had no choice.

I didn’t know my way around the stacks, so I suppose it was dumb luck that I found a book on English poets with a chapter on Keats and an analysis of “Chapman’s Homer.” Reading, I learned that George Chapman was an Elizabethan writer who had translated Homer’s works from ancient Greek to English. That Keats and his friend Charles Cowden Clarke had been up all night reading Chapman’s Homer, so delighted were they by the translation. And that when Clarke sat down for breakfast the next morning, he found Keats’ poem waiting for him on the table.

The analysis walked me through the poem’s references, explained the rhyme scheme of a sonnet and helped me navigate the poem’s middle lines when Keats, in a state of near rapture, hearing Chapman’s “loud and bold” voice, experiences Homer’s verse as if for the very first time:

Oft of one wide expanse had I been told

That deep-brow’d Homer ruled as his demesne;

Yet did I never breathe its pure serene

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold:

I returned to the poem and read again. And I began to grasp, as I had not before, the poem’s final, transformative images:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star’d at the Pacific — and all his men

Look’d at each other with a wild surmise —

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

Those lines sent a shiver up my spine. I can’t explain why. They just did. I left the table and started wandering the stacks, pulling books of poetry and criticism randomly off the shelves. I must have been there until two or three in the morning. I remember to this day pulling one book from the shelf and laughing out loud: Seventeenth Century English Minor Poets. Really? English minor poets? Of the 17th century? Who thinks about such things? Who writes books about them? I left the library and walked back to my dorm. I knew that morning I wanted to be an English major.

Many missteps, more than I care to count, since that night in the library. But it was a beginning.

—John Duffy, William T. and Helen Kuhn Carey Professor of Modern Communication in the Department of English.

In the summer of 1977, several events took place that forever shaped my worldview. I began high school, which I anticipated eagerly, my older brother by one year having told me of the joys therein. My parents’ divorce was finalized, fracturing my trust in all things familiar. Most dramatically, I read Richard Bach’s Illusions, the less well-known follow-up to his bestselling novella Jonathan Livingston Seagull. Of the three events, I’m not sure which had the greatest impact on my life, but I’ve reread Illusions more than 30 times, finding new insight each time. Meanwhile, I haven’t visited my high school in decades and my folks are still haggling over the spoils.

In Illusions, Bach travels throughout America giving biplane rides while reflecting on the meaning of life and dispensing wisdom. As an unmoored teenager, I read Bach to mean that the world is an illusion, that each of us must follow our own spiritual quest and that we are responsible for our own happiness. I was receptive to that message then . . . and now.

—Richard Pierce, associate professor of history

My mother is a children’s literature expert; her work as an elementary reading teacher supported her and her daughters after my parents’ divorce. So it was only natural that, when my father died suddenly just before I began high school, she would recommend that I read a book. That book was Madeleine L’Engle’s A Ring of Endless Light. The title adapts the unnervingly brisk opening of Henry Vaughan’s 1650 poem “The World”: “I saw eternity the other night, / Like a great ring of pure and endless light.”

The novel tells the story of a teenage girl whose grandfather is dying; she lives with him during his final summer. The grandfather, a retired minister, has a library full of 17th-century devotional writers — John Donne, George Herbert and Vaughan chief among them. And his granddaughter is interested in poetry; she imitates the gleanings she takes from his favorite writers, thinking with and through them about death, life and faith.

At age 14, through the haze of grief, I first encountered the writers I now study and teach. The conversion wasn’t instantaneous: It would take another 10 years before I realized the importance of that early introduction. But it was that book that first welcomed me to the light.

—Susannah Monta, Glynn Family Honors Associate Professor of English

I was late to the beauty that is Alice Walker’s writing. Before picking up The Temple of My Familiar, I had never read a book connecting stories over time, culture and race as Walker does. Her style — precise, rhythmic, exhortative — certainly drew me in, but it’s her elaborate plot work that upended my thinking, more so and differently than most everything I’d read prior. This novel shook me; I often go back to it to think about how Walker bridges people and places, painstakingly constructing a poem of a lesson on history and prejudice and power.

Walker made me realize how lopsided my Western-focused education had been. I was upset I hadn’t even heard of her before then, much less been taught her works. I’d read The Iliad three times during high school and college, and not once was it as meaningful and instructive to me as the hours I’ve spent poring over The Temple of My Familiar again and again.

Best known for The Color Purple, Walker is the first author whose catalog I read in its entirety as an adult. As soon as I’d devoured it, I inhaled critiques of her writing, which helped me understand that — despite her fame, talent and intellectual bona fides — she has continued to be punished with the very bigotry and misogyny she’s pushed back against in her work.

—Rachel Fulcher Dawson, associate director of research operations, Wilson Sheehan Lab for Economic Opportunities, and concurrent adjunct professor in the Education, Schooling and Society program

1989. I was a doctoral student in history, anxiously searching for a dissertation topic. Bouncing from one idea (the draft during the Vietnam War) to another (farmers in 19th century California) I couldn’t decide. Then I read J. Anthony Lukas’ magnificent, just-published and Pulitzer Prize-winning Common Ground.

Decision made. Lukas traced Boston’s 1970s busing crisis through the experience of three families and managed to convey the intractability of the city’s racial history while never losing sight of its all-too-human dimensions. His emphasis on the conflicted role of Boston’s Catholic Church inspired my own scholarly efforts, as did his crisp prose and empathetic analysis. I wrote him out of the blue to ask permission to look at his interview notes, just deposited in an archive. He responded immediately with a cheerful “yes.” The notes were not especially useful. But that small encouragement from a famous author meant something, too.

—John McGreevy ’86, Charles and Jill Fischer Provost and Francis A. McAnaney Professor of History

Louise Fitzhugh’s book Harriet the Spy was published in 1964, the year I was born. I probably first read it when I was 10 years old — and I reread it endlessly. Harriet appealed to me because she was an urban kid, while I was growing up in the suburbs. She had what seemed to me exotic and sophisticated tastes: She ate tomato sandwiches, while I ate peanut butter and jelly. She had an imperious nanny, while all I knew were stay-at-home moms.

Harriet rode the subway and went to art museums. Her parents were checked-out intellectuals, which meant Harriet was neglected in the best way — free to roam her city. She was a tomboy and would-be writer who observed city life and people’s habits, not only in public spaces but by peeping into windows and even sneaking into homes.

Personally, Harriet made me want to raise my kids in the city, which I did. Professionally, my book The Apartment Plot: Urban Living in American Film and Popular Culture, 1945 to 1975 allowed me to operate like Harriet by looking into cinematic apartments and the lives represented there; Fantasies of Neglect: Imagining the Urban Child was inspired by stories like Harriet the Spy that imagined kids as autonomous and spatially mobile, able to navigate city streets.

—Pamela Robertson Wojcik, Andrew V. Tackes Professor and department chair of film, television and theatre

During the 2017-18 school year, I participated in the Seeking Educational Equity and Diversity seminar at Notre Dame, which gave me the time and space not only to learn and better understand inequities within educational systems, but also to reflect on my own perspectives and actions. As a part of the seminar, we read Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption by Bryan Stevenson, an incredible book about the lawyer and activist’s work to found the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit organization that represents prisoners serving unjust sentences, and his effort to overturn the conviction and death sentence of a Black man in Alabama.

The book had a transformative impact on me — I even made my wife and children spend spring break visiting the initiative’s Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery. Stevenson’s work has made me more aware of injustice in the United States and reinforced my commitment to be equitable and inclusive as a professor and educator.

—David Go ’01, Viola D. Hank Professor and department chair of aerospace and mechanical engineering

I immediately think of old books: encountering, as an angsty teenager, the alluringly alien world of Pascal’s bracing Pensées, or jaw-droppedly reading Augustine’s Confessions in an Episcopal cathedral in Spokane, Washington, as an undergraduate. But a more recent book also comes to mind: Mark Noll’s The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind. I had fallen in among fundamentalists who were fond of disparaging the importance of study, saying that books would burn but souls were eternal. Noll’s book offered a scathing critique of such an outlook, demonstrating the historical roots and development of a very American, low-church way of thinking, and calling for evangelicals and other people of good faith to wholeheartedly embrace the vocation to an examined life. Noll gave me the permission I had secretly craved to hone my intellectual gifts, such as they are, and to work toward a synthesis of academic learning and Christian faith — and even more, to pursue academic learning as an expression of that faith. I trace back to the summer when I read that book the first stirrings of a call that would lead me to Notre Dame.

—David Lincicum, associate professor of theology

It wasn’t the accounts of public humiliation triggered by Professor Perini’s condemnation of underprepared students in his contracts course, occasionally provoking them to tears; nor was it Scott Turow’s descriptions of cutthroat competition and the palpable undercurrent of exclusion that inspired me. Yet those sections of One L: The Turbulent True Story of a First Year at Harvard Law School didn’t repel me, either. Perhaps I’m unusual in this respect, but I was a professional ballet dancer when I read the book, and although what happens on stage may be pretty, behind the scenes is frequently anything but. Rather, what moved me to wrap up my dance career and apply to colleges was the passion, dedication and drive that characterized the students Turow wrote about.

Part of ballet’s appeal for me was its extremity: It was all-encompassing, a calling that demanded 100 percent of my heart and soul. I didn’t end up pursuing law. The unanswerable questions confronting Turow remained unanswerable for me, and philosophy better accommodated my irresolution. Nonetheless, One L showed me the affinity between studying for the bar exam and practicing at the ballet barre and modeled how to find meaning and purpose in an academic pursuit.

—Barbara Gail Montero, professor of philosophy

For me, it’s the 2015 encyclical Laudato Si’ on care for our common home. It was — and still is — the most forthright and accurate statement on climate change for the lay public that I have ever seen. But it’s more than that. Pope Francis lays out so clearly the ways in which climate change is not so much a science issue as a societal one. The roots of the problem lie in the greed, materialism and selfishness baked into our infrastructure and into ourselves. But Francis also carefully lays out a path toward solutions, starting with reassessing our personal relationship to God the Creator and all of Creation and working toward the reform of our governing structures from the local to the global. This approach launched me into a new career that has culminated in my appointment as director of the minor in sustainability studies. The encyclical is required reading and, in many ways, the syllabus for my course. In translation, “Laudato si’” is the beginning of St. Francis of Assisi’s “Canticle of the Creatures”: “Praise be to you, my Lord, with all your creatures. . . .”

—Philip Sakimoto, professor of the practice in physics and astronomy

Nothing changes your life like having a child, but sometimes a book comes along that changes your outlook so dramatically that you develop a lifelong relationship with it. And when that book arrives as you are having a child, the effect can be profound.

It happened to me in 2005 when our first son was born and I happened to be reading Neil Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death. Like most young parents, I was wondering what kind of world we were bringing our child into. Postman’s account of a world transformed by the television medium provided a lot of answers that I didn’t even know I was looking for. He explained how media technologies shape the culture and our consciousness. It’s not so much the content of the media, he argued, but the forms themselves. He quoted Marshall McLuhan, who famously said, “The medium is the message.”

I later learned that McLuhan was a devout Catholic who believed the Eucharist was the ultimate expression of “the medium is the message.” Christ’s Incarnation was the medium that fulfilled the “content” of the biblical law and the prophets. Postman helped me understand that TV, and now the internet, are not incarnate technologies. Despite all their social influence, they cannot replicate the flesh and blood experience of human contact.

As a new father holding my newborn son, I knew I needed to privilege human touch over touchscreens. I have since developed a program at the McGrath Institute for Church Life to help parents and Church leaders navigate our digital world with wisdom and prudence, thanks to professors Postman and McLuhan.

—Brett Robinson ’97, associate professor of the practice and director of communications and Catholic media studies, McGrath Institute for Church Life

I grew up visiting many Orthodox monastery libraries with my father, a philologist who studied Byzantine Church history and neoplatonic philosophy. Our travels included the monasteries on Mount Athos, a monastic semiautonomous republic situated on a peninsula in the western Aegean Sea. Years later, encountering From the Holy Mountain: A Journey Among the Christians of the Middle East by William Dalrymple, I was transported back to those days and was rewarded with a newfound understanding about the branched development of Islam and Christianity and how much of both religions was derived from the same roots.

Dalrymple starts his journey from Greece to Egypt by way of Turkey, Syria, Lebanon and Israel, following a 6th century travelogue found in one of the monasteries of Mount Athos. Following the footsteps of two monks, John Moschos and his pupil Sophronius the Sophist, he travels from Constantinople to the Coptic monasteries of southern Egypt, describing both what the monks found in the 6th century and what he finds during his own travels.

What is striking in the description of the ubiquitous thriving monastic culture that existed throughout Byzantium is the enormous diversity in the forms of Christian worship and beliefs prior to the religion’s more central organization and administration. Dalrymple notes that in many ways, Islam as it would emerge would have been quite difficult to distinguish from the broad range of Christian practice at that time. Many of the worship rituals of today’s middle eastern Christians retain their early roots and are similar to those of Islam.

In this insightful book of time travel, Dalrymple describes the monks’ journey in detail, ranging from descriptions of ascetic Stylites who spent their lives on top of abandoned pagan pillars to the monks’ sharp sense of humor. Through this book I gained a greater appreciation for the range of religions in the region today and the complexities of today’s religious hegemony.

—Joannes Jacobus Westerink, Joseph and Nona Ahearn Professor in Computational Science and Engineering

The late Clayton Christensen was a business scholar known as the father of “disruptive innovation.” His 2012 book, How Will You Measure Your Life?, highlights decisions he had to make that aligned with societal norms but went against his own values. Here, Christensen has focused on family, faith and personal well-being beyond one’s career and wealth.

The seemingly simple practice Christensen outlines has helped me navigate some of my own challenging decisions. My family and faith are my foundation. They have helped guide me in the experiential learning projects that have become a signature aspect of my teaching, whereby I ask students to apply what they are learning in the classroom to have a measurable impact on the most vulnerable members of society.

I also incorporate Christensen’s book into my Designing Your Life course, where students grapple with questions about how to use their time and talents effectively. His message can be summarized simply: to live a life that matters, one you will be proud of when you reach the end of your earthly journey.

—Wendy Angst, teaching professor of management and organization

Reading Christ and Culture for the first time at the tender age of 24 — it was assigned in a graduate course at the University of Chicago — I was taken by the clarity it brought to the farrago of Christian history in all its controversies and contradictions. I have returned to it on several occasions, not so much as a way of classifying Christian groups and movements, but rather as a reassuring reminder that the discerning student need not be paralyzed by the overwhelming “data” of history. We may instead rely, however tentatively, on the power of reason to identify underlying patterns and “family resemblances” among otherwise incomparable societies and cultures.

Christ and Culture provided crucial insight into the way ideas and beliefs shape social attitudes and practices and gave me a new way of thinking about history, theology and how we construct a “reality” or worldview from the dizzying varieties of beliefs and practices we encounter

Written by H. Richard Niebuhr, a prominent Protestant social ethicist, the book sets forth five distinct models of belief and behavior abstracted from human conduct over the centuries since the life of Christ. These models describe how different individuals, groups and movements, extrapolating from their interpretation of Jesus’ responses to the values, norms and practices of first-century Palestine, the society in which he lived, chose to respond to the societies in which they lived. They all asked, in today’s parlance, “What would Jesus do?” in their circumstances.

As he explains the five models, Niebuhr provides examples from the history of Christianity. Tertullian, an influential theologian of the early Church and a harsh critic of the pagan culture of third-century Carthage, is presented as an exemplar of Niebuhr’s “Christ against Culture” model. One might place in this category contemporary Christians of the United States who denounce American culture as excessively racist, violent, misogynistic and, therefore, decidedly un-Christian.

—Scott Appleby ’78, professor of history and Marilyn Keough Dean of the Keough School of Global Affairs

The dreaded yet inevitable call came: Come home ASAP. He’s bad and may not last the night. The familiar journey home. O’Hare. Aer Lingus. Dublin. N21. On the car radio, a hoarse commentator gasps as Limerick do battle with Kilkenny in the all-Ireland hurling final. Hurling, my father’s game and passion.

The work that shaped my feelings and channeled my grief, during and since, is An Fear Marbh, Colm Breathnach’s suite of poems in his father’s memory. Breathnach celebrates his father, and all fathers, without ever surrendering to sentimentalism or cliché, and offers a guide to remembering and honoring.

The title poem refers to Inis Tuaisceart, the northern island, known locally as An Fear Marbh, the Dead Man, because of its silhouette against the Atlantic sky. An iconic island off the Kerry coast, it is part of the literarily renowned Blasket archipelago, yet is rarely if ever visited. It looms there, a clear marker, often featuring in photographs, but unknown and virtually unreachable. Breathnach uses this no-longer-accessible but ever-present island as a motif to explore and celebrate his paternal relationship: Visible, known, documented and admired but no longer accessible.

This book has the greatest influence on me as I prepare for a semester teaching a variety of texts that deal with death and loss. As the island lies off the Irish coast, my father’s memory is visible just beyond the margin.

—Brian Ó Conchubhair, associate professor of Irish language and literature

A few years ago I visited my pal Riley Sise ’06 in the volcanic highlands of Guatemala. On the far shore of Lake Atitlán, he pointed out a curiously humped hill, Cerro de Oro. Supposedly, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry saw Cerro de Oro in 1938 after crashing his plane nearby. To him, the hill’s strange shape looked like a boa constrictor that had swallowed an elephant, and thus it inspired the delightful illustration in the first chapter of The Little Prince.

I first read The Little Prince a couple decades ago in a course taught by the beloved English professor Tom Werge. Reading Saint-Exupéry’s strange tale of an enigmatic little fellow who’s fallen from his own tiny planet among the stars was like being shaken awake to the most important matters of living on this planet.

It is still the truest book I know about love, friendship, time and loss, a book for almost any occasion and one I frequently give as a gift. Just a few days ago, another friend, Ryan Rogers ’05, sent me a photo of him reading The Little Prince to his toddler daughter.

—Nicholas Mainieri ’06, director, Student-Athlete Transition Program

As a newly minted attorney, I boldly and foolishly believed I could change the world. Global events, 9/11 and my refugee clients’ lived experiences knocked such blind idealism out of me. The more I practiced law, the more I felt helpless — as if nothing I could do would fix the wrongs or right the system.

Rohinton Mistry’s novel A Fine Balance helped me navigate my existential crisis. At its crux, this is a book about hope and despair. The plot centers around Ishvar, Om, Dina and Maneck, friends from different castes and faiths who forge bonds that transcend unspeakable tragedies. As I read of their struggle to survive the “Emergency” declared in India in 1975, they helped me locate the values I wanted to live. These unlikely friends proved to me that our world is not broken beyond repair, that the counterpoints to indifference and destruction are kindness and valor.

A Fine Balance gives us people laboring to repair the tapestry of humanity that avarice, pride and gluttony regularly conspire to tear apart. It continues to call me to use my own threads — my empathy, my feistiness and even my own brokenness — to help stitch back together the hurt, shame and pain we all confront in the world.

—Erin Corcoran, executive director, Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies and associate teaching

professor of global affairs

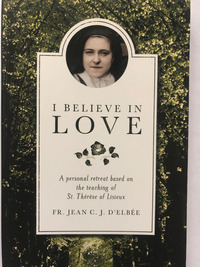

This summer, reading I Believe in Love by Father Jean C.J. d’Elbée, based on the reflective teachings of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, offered me a great meditative way of learning to love joyfully. Throughout the book, the author reminds us of God’s love for man. We witness it through Jesus’s institution of the Eucharist, which bridges us to himself. D’Elbée offers reassurance of the possibility of overcoming the hatred that is pervasive in the world and affirms our confidence that Jesus has overcome the world. These principles are easy to forget when we are preoccupied with temporal matters and personal problems.

I Believe in Love renewed my belief that Jesus gives us peace proportionate to our confidence in him, which leads us to love and abandon ourselves to the will of God. To love Jesus, one must have a great desire to be holy, embrace humility and seek the peace that comes through fidelity to grace. This in turn will radiate to those near us, fulfilling our love of God and neighbor.

—Amelia Lutz, pre-award program manager, Notre Dame Research