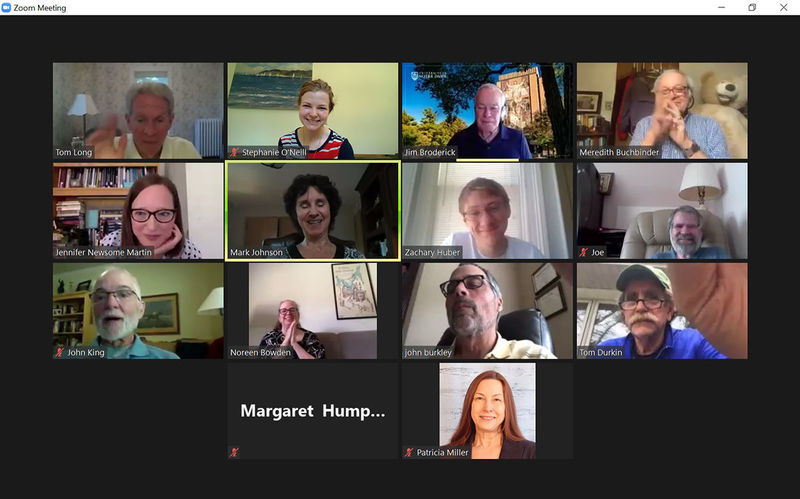

A virtual symposium felt as intimate and intellectually energizing as a classroom seminar. Courtesy of the Program of Liberal Studies

A virtual symposium felt as intimate and intellectually energizing as a classroom seminar. Courtesy of the Program of Liberal Studies

I took a lot of grief as a Notre Dame student back in the ’80s for being a Program of Liberal Studies major. Friends who were not reading the great thinkers from throughout history claimed that PLS was somehow too old-fashioned and out of touch with the changing world. So I take some satisfaction in reporting that, on the contrary, the program has risen to the challenge of the pandemic and provided its graduates with the two things we need most right now: an agile use of technology and a strengthening of community.

My family has been lucky in the pandemic so far. No one has died; no one is bankrupt. We live in a pleasant neighborhood and our children’s school handled the leap to remote learning well. But I feel as if the world is telescoping into this one metro area, this one neighborhood.

The border with Canada, a 20-minute drive and a friendly gateway to adventure since childhood, is closed. All my groups — the Notre Dame Women Connect book club, school Mothers’ Club, yoga class, Boy Scout troop — have stopped in-person interactions. People walking in the neighborhood move into the street to pass me and the dog rather than share the sidewalk. Some will say hello or exchange comments on the weather, but many stare staunchly ahead as if even eye contact will infect them. I’m starting to empathize with the lepers in the Bible.

Rather than cancel the annual alumni Summer Symposium because of the virus, PLS department chair Tom Stapleford and his colleagues decided to take it online in a more flexible and much more affordable format. I registered as soon as I received the email announcement. I chose Eric Bugyis’ seminar, “Learning to be Free,” on the proper place of work and leisure in human life, and ordered or downloaded the readings.

Then I marked the times that I would be at my PLS seminar on the family calendar. If I had registered for all six seminars, I would have been in class for three 90-minute classes per day for the full week. As it was, I declared myself unavailable to my family for 90 minutes on the Wednesday and Thursday of that week, plus time on Sunday and Friday for opening and closing receptions. My sons, who had had more than enough of Zoom classes by then, found all this incomprehensible, but it gave me the sort of happy expectation that I hadn’t felt in months.

It must have done the same for other PLS alums because 70 of them registered for the symposium, almost quadruple the usual number who attend when it’s held on campus. Some signed up for all six classes, but the online format allowed people to take only those seminars that they could fit into their own schedule or that interested them. Participants Zoomed in from 21 states, the District of Columbia and the United Kingdom. They represented every stage of life, from those who graduated this year to those who graduated before I was born and long before Notre Dame admitted women.

Such a range of experience always deepens a discussion, even more so in my seminar about the meaning of work. The 17 of us benefitted from the perspectives of a young woman with her eye firmly fixed on social justice issues, a middle-aged official in local government, a young man with a decided theological bent, a recent grad preparing to teach for the first time, a woman working in support of the arts community, men long retired from successful careers and others. Our two 90-minute meetings were scarcely enough time to start the discussion.

Being PLS majors, we anchored ourselves in our texts: the German Catholic philosopher Josef Pieper’s Leisure, the Basis of Culture; the French socialist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon’s essay on the Sabbath and a recent article from The Atlantic by Derek Thompson called “A World Without Work.” Given the startling immediacy of these issues amid the economic consequences of the pandemic, we couldn’t resist exploring their relevance in our lives.

Our retired colleagues explained how important moments of leisure had been to their career success. We were reminded that artists need leisure to produce their works. Our young theologian took us back to Pieper’s remarks on the necessity of leisure for the human soul. But we kept running into the hard economic truth that in our current economy, leisure is a luxury. What qualifies as the authentic leisure that fulfills the God-given talents of each of us? Is the ability to participate in such authentic leisure a product of education?

By the end of the week, it was clear that the pandemic necessity of gathering online has opened up a world of possibilities for alumni engagement in PLS. A poetry club met by Zoom that Friday. We received a call for short essays about how our education rooted in the Great Books has helped us weather the lockdown and the recent civil upheaval. The department asked us for ideas for one-time events such as performances or discussions of a text.

I, for one, am eagerly awaiting the opportunity to register for whatever comes along. Because I don’t feel as isolated now. Zoom is no longer just a tedious necessity but a channel to a community of fellow Domers of the PLS persuasion.

The jump online has reengaged a community of learning that usually ends with the dispersal of graduation. The symposium by Zoom took us out of our cramped and isolated pandemic selves. To take the time to read a text closely and have the opportunity to discuss it with others who know how to read carefully and argue courteously is to throw a lifeline back to our optimistic, college selves. It has made me feel truly like a part of the Notre Dame family and not just a potential donor or a person who stops by to light a candle at the Grotto on a long-distance car trip.

Ironically, it’s PLS’s unfashionable dedication to deep thought and comprehensive discussions and the crisis of COVID-19 that has brought me back home to Notre Dame.

Megan Koreman is a historian and author of The Expectation of Justice: France, 1944-1946 (Duke University Press, 1999) and The Escape Line: How the Ordinary Heroes of Dutch-Paris Resisted the Nazi Occupation of Western Europe (Oxford University Press, 2018). More at dutchparisblog.com.