Hang on a second. Steve Wrinn wants to find the original email.

An old friend and colleague sent it, and they communicate often, so Wrinn has to sift through the search results to find the specific message. He wants to pinpoint the date and emphasize the routine simplicity of the moment that initiated the greatest success of his career and accelerated the renaissance he hopes to lead at Notre Dame Press.

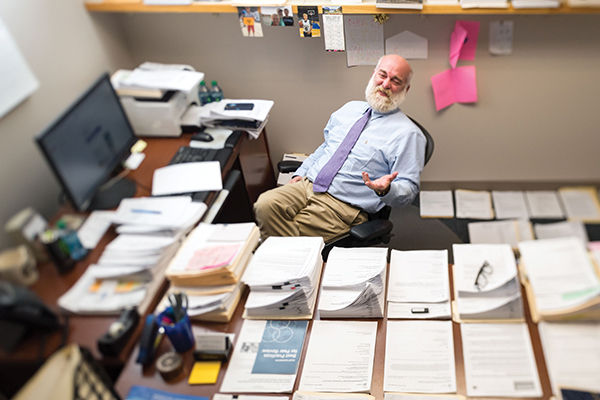

The ebullient Wrinn feels optimistic about the future of Notre Dame Press. Photo by Matt Cashore ’94

The ebullient Wrinn feels optimistic about the future of Notre Dame Press. Photo by Matt Cashore ’94

While he’s looking, some background: Wrinn directs the press, an academic publisher with all the burdensome finances and muffled publicity that a scholarly niche implies. Two years ago, he inherited a house awash in red ink and overlooked on its own campus. He was hired to apply a tourniquet to stop the bleeding, nurse the patient back to health and nurture it toward a long and fruitful life.

That requires the kind of painstaking workaday labor — replenishing depleted balance sheets and unifying a siloed office culture — that 13 years as director of the University of Kentucky Press had prepared him to do. During all those years in an insular industry, Wrinn got to know a lot of scholars, agents, editors and publishers — an invaluable network to draw on to fulfill his Notre Dame mandate.

“Scholarly publishing,” he says, still scrolling, “is all about relationships.”

One of the people he knows well is Jeremy Beer, a former editor-in-chief of ISI Books, the award-winning press of the Intercollegiate Studies Institute. He and Wrinn were friendly rivals over the years. Beer left the publishing business to found a philanthropic nonprofit, but he still shepherds the occasional literary project as a freelance agent.

It was in that capacity that he wrote to Wrinn on — let’s see, not that one . . . maybe this, no, that’s not it either . . . there it is — June 20, 2016, with an offer. Wrinn reads from his screen, for the record:

“Steve, I hope you’re doing well. Sorry I missed you in South Bend last week. Would Notre Dame potentially be interested in the attached project? It’s prestigious and the translations are all paid for.”

After full disclosure about the high-profile university and commercial presses where he was also presenting the works, Beer concluded with a line that heralded Notre Dame’s opportunity to position itself favorably in relation to more esteemed and prosperous competition: “They aren’t looking for a payday as much as an enthusiastic and committed partner.”

“They” refers to the family members of the late Nobel Prize-winning Russian author, dissident and political prisoner Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. The “attached project” was the first English-language publication of the final six volumes of his Russian Revolution opus, The Red Wheel, and Solzhenitsyn’s memoir of his exile, The Little Grain Managed to Land Between Two Millstones.

“I was on the phone in about 10 seconds,” Wrinn says. “I mean, literally.” Exuding enthusiasm and commitment.

Under any circumstances, Wrinn’s enthusiasm is never far from the surface. He’s a gregarious Santa Claus of a guy, white-bearded and ebullient.

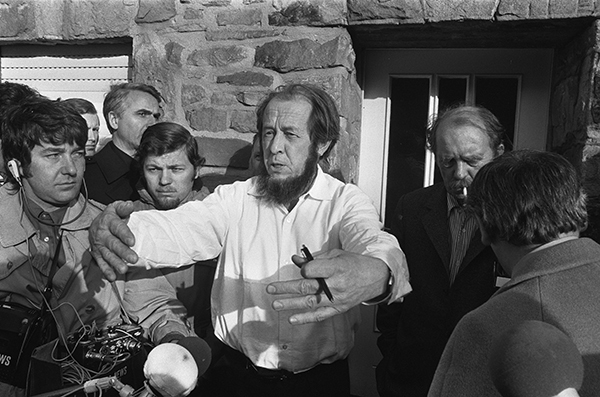

Solzhenitsyn in exile in 1974. Photo by Bert Verhoeff/Anefo

Solzhenitsyn in exile in 1974. Photo by Bert Verhoeff/Anefo

But the unforeseen flare of Beer’s email brightened his eyes even more than usual. Unsolicited in Wrinn’s inbox, less than a year into the job, came a potential giant leap toward achieving his ambition for Notre Dame Press. He would not lose out on this opportunity because of insufficient fervor.

If he couldn’t match his competitors’ financial commitment, Wrinn could offer an unsurpassed intellectual investment. The project offered a path toward realizing an important priority in raising the press’ profile: making its publications central to the larger academic life of the University.

Law professor O. Carter Snead, director of Notre Dame’s Center for Ethics and Culture, offered to support the series and host a conference dedicated to Solzhenitsyn in conjunction with the books’ publication. The Hesburgh Library is working on making Notre Dame the only U.S. stop for an exhibition of the author’s personal effects that is currently touring Europe. And the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections already holds a significant amount of Solzhenitsyn material.

That all dovetails with Wrinn’s vision to make Notre Dame not just his new English-language publisher, but a primary destination for research into Solzhenitsyn’s work.

“What we said is that Solzhenitsyn’s intellectual legacy will be preserved at Notre Dame in a way it won’t be” anywhere else, Wrinn says, through the University’s commitment to use the acquisitions as a catalyst to build a research infrastructure around his literary legacy. “To us, it’s bigger than the books.”

Which is saying something. Few books could be considered bigger, in every sense of the term.

Solzhenitsyn, who chronicled life in Soviet forced-labor camps from his own experience as a prisoner in The Gulag Archipelago, set out as a young man to document the Russian Revolution. Service in World War II, imprisonment, cancer and the throes of 20th-century Cold War upheaval that defined Solzhenitsyn’s storm-tossed life delayed the project he considered his most important.

Born in 1918, a year after the revolution, he researched and interviewed for decades, but did not truly begin to craft the 10-volume cycle called The Red Wheel until the Soviet Union expelled him and he took up residence in Vermont in the 1970s. The full work is made up of four multivolume “nodes,” ten books in all.

Nearly 30 years ago, Farrar, Straus and Giroux published August 1914 and November 1916, the first two nodes of The Red Wheel in English, but combined them into just two books. In Solzhenitsyn’s vision, those were meant to be four volumes.

By that time he also had developed a complicated political profile, on the one hand a towering figure in the exposure and ultimate fall of Soviet communism, on the other an unapologetic critic of Western capitalistic decadence. The latter clouded his reputation in the United States, perhaps part of the reason that funding dried up for subsequent translations of The Red Wheel. An anonymous donor supported the new English versions that Beer brought to Wrinn.

Notre Dame Press is publishing the final six books of The Red Wheel as Solzhenitsyn intended. The first of four volumes that make up Node III, March 1917, appeared in November, translated by Marian Schwartz, a two-time recipient of National Endowment for the Arts translation fellowships whose long list of credits includes Leo Tolstoy’s novel Anna Karenina and Edvard Radzinsky’s biography of Nicholas II, The Last Tsar.

The next three volumes of Solzhenitsyn’s March 1917 and the final node, the two-book April 1917, are under contract and forthcoming as the translations are completed. The first part of the two-volume memoir will be published next fall under the abbreviated title, Between Two Millstones.

Exciting times at Notre Dame Press, where there’s a sense of being on the cusp of something big. And, just as important to Wrinn, a sense of being in it together.

When the first copies of March 1917 were due to arrive in October, Wrinn showed up at a staff meeting anxious to get his hands on one. Colleagues had hidden a copy behind his office door and he sprinted out of the conference room to grab it, thrilled to hold so much of Russian history and so much of the future of Notre Dame Press in a single volume.

“It was a very nice celebration,” Wrinn says. “I feel like that’s just the beginning.”

Jason Kelly is an associate editor of this magazine.