1.

Let’s start at the top: a summer day, a few years ago, an American family of five on vacation in France. Fresh bread eaten, sunblock applied, long walk taken, tickets bought, ice cream sought and found and savored, we found our place in line outside the cathedral, were ushered into the tower, climbed the steps — more than 400 of them — and there it was: Paris, seen from above, or more precisely, Paris and the upper part of Notre-Dame, roof, tower, gargoyles and the rest, blended together before our eyes such that city and cathedral were one.

The delicacy of the cathedral caught me by surprise: the fleurs-de-lis, the orchids atop arches, the stone accents like daubs of icing on pastry, even the lead slabs of the roof, held together by mercurial runnels so soft-looking they might have been laid down the day before.

So, too, did the intimacy surprise me. Notre-Dame was attracting 12 million visitors a year from all over the world, the guidebook said, but the logistics of roof access were such that the five of us were essentially alone up there — as close together as we’d been in the rental car we’d driven to Paris. For a few minutes, this cathedral-and-city view was ours.

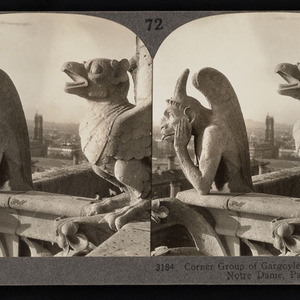

Those qualities come through in the photos I took that day. Mother and child with gargoyle. Older boy and younger boy in profile on either side of a winged, beaked stone creature, and behind them the pitched roof with an apostle statue in the distance and the scalloped tower behind them, so close that you could extend a forefinger and tip it over.

2.

I sure didn’t expect that our visit would wind up being from the time “before” — before the fire that struck Notre-Dame de Paris on the night of

April 15, 2019. You know what happened. Oak beams cut and joined in the Middle Ages swiftly burned through. The lead roof collapsed. The spire fell and crushed a modern altar. The fire burned 15 hours, leaving rubble that hazmat-suited experts operating robots would spend the next two years clearing out.

Nor did I expect what I felt in that moment. As Our Lady of Paris burned, I felt a strong sense of possession. Our Notre-Dame was burning — Our Lady of Paris. Our cathedral might never be the same. That intimacy was there again, pluralized and stronger than concern for “a treasure of Western Civ” or “a jewel in the Catholic crown” could account for.

Maybe you felt the same way. Countless people around the world did. The ravaging of the cathedral called forth grief on a grand scale and spurred a comprehensive collective response. The heads of France-based corporations donated hundreds of millions of euros to support the cost of restoration. The University of Notre Dame pledged $100,000; a fundraiser at the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C., drew $465,000. Tens of thousands of people made contributions. The president of France, Emmanuel Macron, swore that the cathedral would reopen to the public by the time of the 2024 Paris Olympics.

I can’t help but be struck, even awed, by the intensity of the effort, the depths of knowledge and coordination going into the restoration.

The gale of grief also caught me by surprise. All this for a church — a Catholic church! Oh, I know the French love their culture, that Parisians are monument-proud. But there was no great love for the Church in that time of clerical sex-abuse revelations. And there is no great love for Paris in the Catholicism-and-culture precincts where I practice professionally. Among the traditionalists who have entrusted themselves with protecting Catholicism’s future, Paris is typed as a lost city — its Catholics’ faith atrophied, the local observances rote and wan, the French fondness for old things nothing more than the stale perfume of what George Weigel has termed a “decadent Christendom.”

I should have known better. For one thing, the global outpouring of affection for Notre-Dame was a large-scale expression of what I felt personally — that sentiment of people from other lands whose firsthand experience with the cathedral is only one episode in a complex encounter with Europe, Catholicism, the Middle Ages and Gothic architecture.

For another, Notre-Dame has been the focal point of extra-religious feeling for much of its history — and it is those feelings, as much as religious devotion in the strict sense, that have brought so many of us to Paris to pass through the cathedral’s stone portals, gaze at its stained glass and climb its steps.

3.

Ten years ago, in a book called Reinventing Bach, I told a story of the ways “our” experience of music changed once recordings became ubiquitous in the 1930s. I drew on the work of André Malraux, the novelist, adventurer and minister of culture under de Gaulle. Just after World War II, Malraux developed a view of art rooted in “metamorphosis,” as artists across time articulated artistic forms — painting, statuary, fresco — into distinctive styles. In The Voices of Silence, he updated his idea to account for the effects of photography on art. Malraux saw images of artwork enabling a “museum without walls,” which brought different epochs and societies together the way museums with walls had done in the 19th century. Artworks could be “estranged . . . from their original functions” and placed in dialogue with works from other times and cultures. Malraux was exhilarated by the development, seeing it as akin to the “metamorphic” creative process.

It seems to me that in recent decades works of art with walls have undergone a similar metamorphosis. Churches, fortresses, villas, castles; the Pyramids, the Tower of London, Wrigley Field: through snapshots, audio and video guides, documentaries, the smartphone and social media, a trip to a place of renown has become a profoundly mediated experience in which our encounter with the place is hardly distinguishable from our encounter with images of the place. We recognize this transformation. We are involved in it. In a place like Venice, it is so complete that the city is at risk of becoming an image of itself, emptied of residents and populated by tourists who must buy tickets in order to enter the city and sign a release agreeing to be surveilled while there.

Something like that has happened at Notre-Dame. The seat, or cathedra, of the Archdiocese of Paris is also and especially a site. The pictures, the guidebooks, the online bucket lists stoke our anticipation to a degree that the place itself can hardly satisfy. The time spent waiting outside the cathedral is longer than the time spent looking around inside it. Among my most vivid memories of my family’s hour there is the carved wood scale model of the cathedral lit up in a glass case — a 3D representation of the building we were standing in.

4.

Strange to say, then, that the sense that Notre-Dame is “ours” may be an emotion called forth by digital media. And yet for most Americans, an encounter with Notre-Dame has been a deeply mediated experience all along — an encounter via earlier forms of media and technology.

I remember sitting legs folded on a dorm-room floor with H.W. Janson’s giant History of Art open on my lap. Gothic art, in Janson’s account, was the “modern” style of its time, emerging in France in the 12th century and spreading with astonishing rapidity through Europe over the next hundred years. It was an urban style: As cities grew in size and importance, so did their cathedrals. And it was a Catholic style akin to the philosophy that St. Thomas Aquinas was developing in Paris: “Gothic builders . . . brought the logic and clarity of engineering principles to bear on revelation, using physical forces to create a concord of spiritual experiences in much the same way the Scholastics used elucidation and clarification to build their well-constructed arguments.” Architectural order was an analogue to the divine order, of which God himself was the architect. The pilgrim’s entry to a Gothic church was a structured religious experience, a passage from daylight to darkness to the light of stained-glass windows, and this “liminal, or transitional, zone signaled that visitors had left the temporal world behind.”

The pilgrim’s entry to a Gothic church was a structured religious experience, a passage from daylight to darkness to the light of stained-glass windows.

I read those pages avidly, and as I contemplated the black-and-white photos of French Gothic cathedrals it was as if I, too, had left the temporal world behind. Here was a religious drama wrought in stone across an epoch, with Notre-Dame at the center of the drama. Saint-Denis, built a little earlier, was lopsided, with a bell tower on the right but not the left. Chartres, begun earlier but reconfigured after a fire, had two very different towers, one squared off, the other angular. Notre-Dame’s towers were matched. The west façade was divided into thirds horizontally and vertically. The Old Testament figures lined up in a long row over the entrance in perfect unity.

I had not yet traveled to Europe, but I recognized Notre-Dame de Paris as a distinctly Catholic expression of the qualities Aquinas celebrated in art: wholeness, harmony and radiance. And I grasped — for the first time, maybe — the sense of catholic as all-embracing, a quality of breadth that, at the great medieval cathedrals, involved place, architecture, design, sculpture, glasswork, liturgy, music and communal striving, and brought them radiantly together.

5.

It’s through Gothic Revival architecture, more than from art history books, that most Americans have come to know the Gothic.

In upstate New York, where I grew up, Christmas Eve Mass on television was from St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Fifth Avenue, not St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. St. Patrick’s was spoken of in the same breath as Madison Square Garden and Macy’s — as a destination without compare, the original and best — and it was only later that I learned that “our” cathedral was modeled on the cathedral in Cologne, Germany. For us, a cathedral was a Gothic cathedral. I didn’t yet know that Gothic Revival was a revived architectural style at all.

Paradoxically, all the modern churches built in the suburbs during those years made this sensibility more true, not less so. The glassed-in, carpeted, trapezoidal space with parking lot was the place you went on Sunday, but the Gothic — that’s what a church looked like.

We see Gothic Revival churches at big-city intersections, on prairie skylines, on boulevards amid Craftsman houses, girdled by highways, claiming pride of place on college campuses — and here and there (in New Orleans, for example) facing a square, European style.

Most of those Gothic churches are not Catholic churches, which may be one reason that American Catholicism prized the Gothic Revival. Our stone or brick Gothic churches were a form of assimilation. We’re here, they said. We’ve arrived. Through them Catholics at once asserted respectability by building in a broadly accepted style and claimed back for Catholicism the style that — because the Gothic was perfected prior to the Reformation — was “ours” in the first place.

When they went up, our Gothic churches, many of them, expressed the actual memories of European immigrants. They were reminders of a place and a culture people had left behind, often reluctantly and out of need. For later generations, they have embodied a sense of the past, of origins, rooted in the cultural imagination and have taken on an American character through their surroundings — metamorphosed — along the way. The Gothic church modeled on the one in a square in Brussels or another in a grassy close in Yorkshire stands in juxtaposition with the red barns and traffic lights and corner taverns of the U.S. of A. In situ, these churches have become ours, and so has the history they carry with them.

At the same time, Gothic Revival churches are standing reminders that the United States was originally mission territory for Roman Catholicism and Protestant denominations alike. Reminders, that is, that Christianity is not indigenous but was established through the displacement of prior cultures and beliefs, that Christianity is no more “native” to the U.S. than it is to Brazil, say, or South Africa, or Nagasaki, or even Rome. Reminders that American Catholics shouldn’t see European Christian culture as “ours” as Catholics by any birthright or in any exclusive way.

These structures, built in a revival of a historical style, now belong to the past, too. And yet they are still standing. Long after the Gothic Revival, American Catholicism is still characterized by the architecture of Europe, owing to Catholic reverence for tradition, to the clunkiness of so much modern church design and to the solidity of architecture in comparison to other forms of culture. Language, cooking, dress and music are relatively portable. Architecture is less so. A church, once built, is prone to stay in place. Even as the liturgy, the banners, the outfits worn to Mass change, Our Lady of Perpetuity endures, its spires and stained glass at once masking the changes going on inside and abiding in counterpoint to them.

6.

So it is that an American Catholic visiting Notre-Dame for the first time arrives heavy-laden with associations.

My family tree has French Catholics on both sides — Elie from French Canada, LeRoux from Normandy. When I arrived in Paris for a weekend during a college summer, I was met at the Gare du Nord by Père Roland Noël, a second cousin. The black shirt and clerical collar he wore with blue jeans identified him as a priest; the shape of his head and the curve of his smile revealed him as kin.

That weekend Roland showed Paris to me. We zipped from sight to sight in a tiny Renault, his friend Daniel in the passenger seat, I in the back, the windows rolled down. We piled out near Notre-Dame. Was there a crowd, a wait, a security guard? I don’t remember any. I don’t remember much about the interior, either, other than the hum of voices and splotches of light from the stained glass. Stronger in my memory is the sense that I was seeing the Notre-Dame, queen of the Gothic. This was the Our Lady that preceded all others. This was the Notre-Dame that preceded the university in South Bend. This was — a Kantian term from philosophy class came to mind — the thing itself.

Outside, Daniel took a snapshot of the two cousins, a solidly built prêtre and a still-slender American standing before the stone arches.

I spoke French continuously for the first time that weekend; found myself “thinking in French.” But I didn’t wind up feeling possessive of Paris. Paris was Roland’s city, not mine. (Rome, a month later, was different: There, alone, with no Italian heritage to speak of, I was seized by belonging, a Roman Catholic in Catholic Rome.)

Through much of its history, Notre-Dame has been a liminal space — a space between religion and art, between the local and the universal.

Later I learned the historical basis for my perceptions. Where Roman churches are expressive of Roman Catholicism, Parisian churches have long been seen as expressive of French culture broadly — and the French feel possessive of them. The historian John McGreevy ’86, now the University's Charles and Jill Fisher provost, sets this out in his new history of Catholicism since 1789. After the French Revolution the cathedral was rechristened a Temple of Reason. Napoleon was crowned emperor there in 1804. Charles de Montalembert, ardent French Catholic that he was, identified Notre-Dame with the national character, calling it in McGreevy’s paraphrase “the centerpiece of French civilization.”

I didn’t fall for Paris that summer, didn’t feel ancestral French Catholicism’s full embrace. And yet the Gothic had claimed me. I was in a religious crisis, trying to close the gap I felt between the personal claim Catholicism had on me and the grand, certain claims the Church made about its role in the world. It was in England that the crisis played out: York Minster looming over the high street; Canterbury Cathedral, bold and proud from afar; Salisbury, where an English friend and I ascended a spiral staircase to the bell tower and then raced back down to make the last train to Bath.

Those churches, built before the Reformation, were consecrated to the Church of England. Fresh from reading the Apologia, I felt a Newman-induced Catholic sadness over “our” loss of them, and the diminishment — so the triumphalist argument went — of great Catholic churches into English heritage sites. But the churches themselves outshone the ecclesial quarrels over them. The beauty and intricacy of the Gothic suggested that textbook distinctions between Catholicism and Protestantism were inadequate to the history at hand. Religion was complicated and the complexity of it was manifest in these places, the silence of the old stone more expressive than any doctrine.

7.

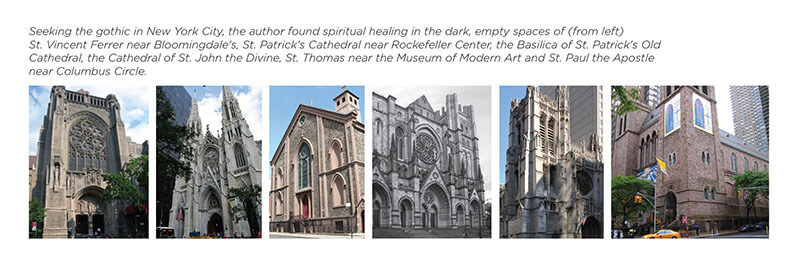

Back in New York, I stalked the Gothic. 1987: The Black Monday stock-market crash and the swift, sharp depressing of the local economy that followed had left the city a neo-medieval place — mendicants in rags roaming the streets, encampments arising overnight in the parks and on the peripheries. At college, I’d been sexually violated during spiritual direction by a Jesuit priest; now, out of school, I sought religious experience that didn’t involve religious people, clergymen especially. Mainly, I sought it in dark and empty churches: St. Paul the Apostle near Columbus Circle, St. Vincent Ferrer near Bloomingdale’s, St. Thomas round the corner from the Museum of Modern Art, Grace Church on the way to Greenwich Village. I prayed. I fidgeted. I blanked out. I read The Interior Castle and The Cloud of Unknowing. I was less than fully alive but felt more alive in these places than anywhere else — the stained-glass, saint-supervised, arched spaces correlating to an interior life whose presence I felt keenly but was having trouble accessing.

The Cathedral of St. John the Divine was a perfect place to feel religiously lonely in: vast, sooty, unfinished, torn between period-correct Tudor evensong and the New Age saxophonings of Paul Winter.

The Cloisters, in upper Manhattan, was likewise conflicted: a chapel and four cloisters uprooted from France and Spain at some Rockefeller’s behest, shipped to the New World and reassembled on a bluff overlooking the Hudson as a museum of medieval art. It was so far uptown as to require a day trip. I would stand in the colored light from the stained glass and try to imagine myself in Europe — at Saint-Denis or Sainte-Chapelle or Notre-Dame.

These were liminal spaces, but in different ways than Janson’s sacred architect once had in mind. Their metamorphoses were plain to see. They were patchworks of worship, art, sightseeing and New York high society — repurposed structures consecrated to mixed motives. This heterodox Gothic felt right — more suggestive of the interior life as I found it than pure Gothic did. It left the door open to the crypto-religious.

St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral was an anomaly: a Gothic church named for an Irish saint in the heart of Little Italy. It must have been closed when I passed by — I don’t remember going in. I couldn’t have guessed that I’d be married there 10 years later.

8.

All the while, the Gothic cathedral par excellence stood implacable in Paris, where I’d left it that summer abroad. Tourism to Paris grew more broadly international, taking in visitors from Japan, from the European countries long walled off by Communism, from Vietnam and China. The city hosted Pope St. John Paul II’s World Youth Day, opened itself to more than a million Muslim immigrants, was scarred by Islamist violence, and was envisioned in post-religious terms in Moulin Rouge and Hugo. The tech industry developed new ways for us to mediate our encounters with places of renown: the screenshot, the travel blog, the selfie, the social-media post. All the while, Notre-Dame de Paris stood more or less unchanged; all the while, our Notre-Dame was changing.

Now Notre-Dame, broken open by fire, is being put back together again.

The fire at once abandoned the cathedral to the world of representation and restored it to its roots. It reminded us that the cathedral is a very old and very fragile construction of wood and stone and lead and plaster — an actual edifice in a particular place. At the same time, the fire underscored its role as a locus for the imagination. A call for propositions about how best to restore it elicited surreal ideas: a glass roof, a roof garden, a cathedral-size rooftop swimming pool. The French director of The Name of the Rose made a documentary with Our Lady as the “international star” and fire as the villain, at once elemental and diabolical. The damaged cathedral, clad in white fabric, was likened to the “wrapped” works made by the Paris-based conceptual artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude.

National Geographic put Notre-Dame on its cover a few months back, an elaborate feature package about the restoration. I bought the issue on impulse at Washington’s Union Station — my first Nat Geo in ages — and read it all the way to New York, wholly absorbed. It was like a journalistic update of David Macaulay’s classic illustrated book Cathedral. A photo spread of the fire-pitted cathedral seen from above . . . another of workers in respirators cleaving like rock climbers to the stone walls . . . sectional diagrams of the cathedral’s innards . . . an enlarged view of a core sample showing how the heat had stressed the stone — I turned the pages with a curiosity I remembered from boyhood. To be more precise, I felt a childlike passion for an encounter with Catholicism and the arts that has been a shaping force in adulthood.

The National Geographic package stressed that Notre-Dame has been restored before. During the French Revolution, anticlerical citizens struck the heads off the Old Testament prophets; in 1831, the cathedral was ravaged by an angry mob. The restoration begun in 1844, and carried out across the next two decades under the direction of Eugene Viollet-le-Duc, gave us the famous “grotesques” — the gargoyles — that are today Notre-Dame’s most beloved attribute. It was also the source of the 12 sculptured apostles convened in seeming perpetuity on the roof. And it produced the conical spire that crashed through the roof during the 2019 fire.

That history is reassuring. It reminds us that Notre-Dame was already a survivor when the fire struck. And it affirms that Notre-Dame as we came to know it was an imperfect structure, not a pure medieval ideal but an edifice that bore the marks of several ages, taking them into itself over time.

The fire left Notre-Dame unfinished — again. The cranes and scaffolding are the outward signs of metamorphosis.

The present renovation involves artisans and experts from across Europe. A firm from Italy directs the painstaking removal of lead dust from the stone walls. Another from Germany is working on the stained glass. Those nations were just consolidating when Viollet-le-Duc took his turn. A century ago, they were at war with one another. Now they are part of a transnational union — and Notre-Dame, for so long a symbol of France, is seen to represent European culture.

The renovation is not uncontroversial. The plan to create a “cooling park” around the cathedral will be hospitable to tourists but will further separate the cathedral from the everyday street life of Paris. Another initiative will pocket an immersive multimedia exhibition into the rear of the nave, drawing accusations that the restorers are exceeding their brief to reconstitute the cathedral in its “last known state” before the fire. “What the fire spared, the diocese wants to destroy,” an article in the conservative French daily Le Figaro put it. The worry is that the restoration will replace a Catholic house of worship with a world-heritage site, that it will banish the medieval otherness of the cathedral in a bid to make it “relevant.”

Those are concerns I share. I shudder to think that a collective sense of possession might lead our peers to renovate the cathedral reductively in “our” image — that of the present age. But I can’t pass over the plain truth that — Catholic faith and French ancestry notwithstanding — my own connection to Notre-Dame is a construct, made of history and the imagination. And I can’t help but be struck, even awed, by the intensity of the effort, the depths of knowledge and coordination going into the restoration. On some level, it’s akin to the collective effort that raised the cathedral in the first place, and it may be that future generations will marvel at 21st-century craft and cooperation.

9.

Nearly nine centuries after it was built, the cathedral on the Île de la Cité is still standing, still “ours” in one way or another. Unable to enter, visitors flock as if to Our Lady’s bedside to see this recuperating survivor — and then post images of themselves and the shrouded structure to Instagram.

For some, Notre-Dame is a reminder of the past — of what we have lost. For some, she stands for what is still present to us in our present moment.

Through much of its history, Notre-Dame has been a liminal space — a space between religion and art, between the local and the universal. It is at once cathedra and catholica, a seat and a comprehensive space where many things come together.

Can the restored Notre-Dame be both? I think so. I hope so. I suspect she is already, made so by our eagerness to see her whole again and by the depths of our concern for how she turns out.

Paul Elie is a senior fellow in Georgetown University's Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs and a regular contributor to The New Yorker. He is the author of The Life You Save May Be Your Own and Reinventing Bach.