University of Notre Dame Archives

University of Notre Dame Archives

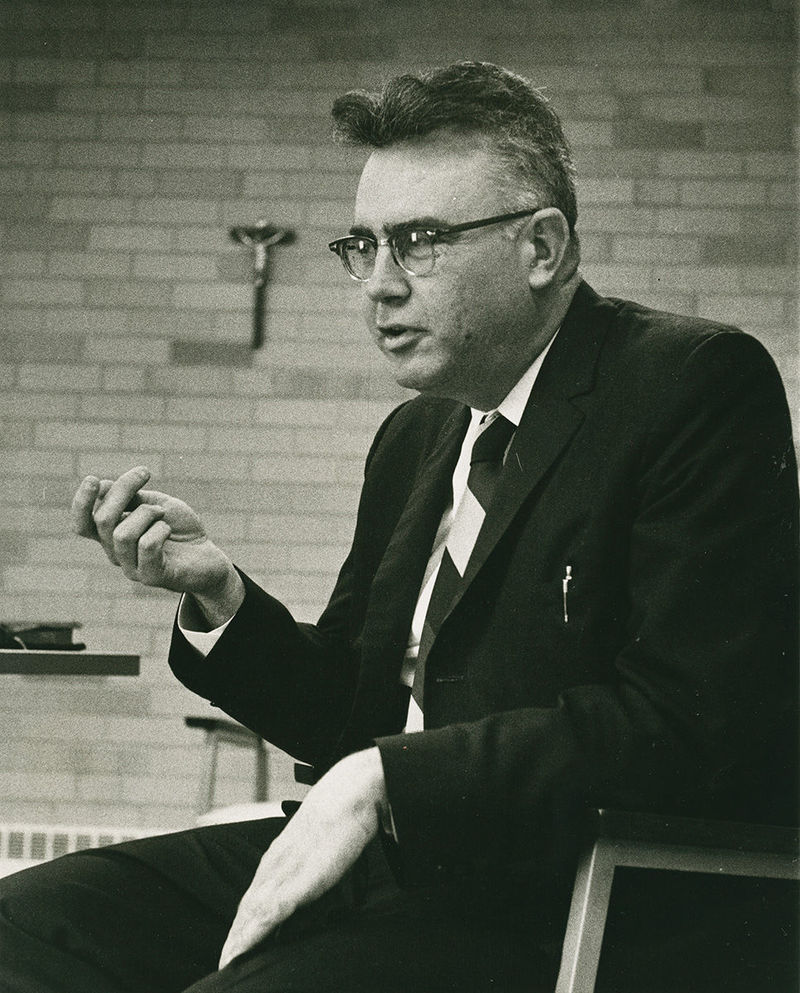

Outside the first-floor classroom in O’Shaughnessy Hall where he taught in the spring of 1970, Professor Joseph Evans carefully observed a tree. He encouraged the students in his Basic Concepts of Political Philosophy course to ponder the essence of the tree “treeing.”

Evans’ love of nature was apparent, but his deeper message was that he wanted us to look attentively at the world as we searched for deeper meaning. For concrete-thinking science majors like me, this fundamental challenge to our ways of thinking was so enriching.

Joe Evans ’51Ph.D. died 40 years ago this past summer, on August 24, 1979. He was 57 years old. Today he is part of a pantheon of renowned Notre Dame faculty members that includes Frank O’Malley ’32, Emil T. Hofman ’53M.S., ’63Ph.D. and Father John Dunne, CSC, ’51 among many beloved others.

In 1970, Evans was the first recipient of the Rev. Charles E. Sheedy, CSC, Award for excellence in teaching. Father Ted Hesburgh dedicated the fountain near the LaFortune Student Center in Evans’ honor in 1980. And a plaque near Malloy Hall now helps to keep his memory alive, remembering Joseph W. Evans, “philosopher, teacher, and friend,” the words engraved in the metal just as Evans had engraved his insights on us.

Evans was born in a small town in southern Ontario, and earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in Canada. Joining the Notre Dame faculty as he finished his doctoral work, he co-founded the Jacques Maritain Center in 1957 to perpetuate the influence of the great French Catholic philosopher’s thought at Notre Dame, and would serve as its first director until shortly before his death.

Once when he was speaking of his affection and admiration for Maritain — who as the leading Thomist of the 20th century had visited campus several times after World War II — one of us asked Professor Evans if the two men had ever had a serious disagreement. He recalled how Maritain had never addressed the issue of capital punishment, and how he planned to take up this important matter during a lunch meeting. How did Maritain respond? Evans replied that, before he’d had the opportunity to pose the question, “lunch ended.” I detected a deference to a revered mentor regarding one of the few issues upon which they did not necessarily share the same view.

Although Evans’ scholarly work focused on the writings of Maritain and St. Thomas Aquinas, he also shared with his students his love of the philosopher Josef Pieper, of poets Gerard Manley Hopkins and William Blake, and of the journalist and aviator Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. Saint-Exupéry’s novella, The Little Prince, which he wrote and illustrated in 1942 while in exile from the war, was the focus of much thought and discussion in Evans’ political philosophy class.

The story is told by a pilot who is stranded in a desert where he meets a charming little boy from a small planet. The prince’s youth belies his wisdom and insight — life lessons he shares through his stories and conversation. Evans used those lessons to teach us the virtues of looking below the surface, of maintaining a sense of wonder, of thinking like a child.

His warmth and genuineness were noteworthy. He was often seen on late afternoons seated on the low wall not far from the Moses statue at the library, reading a daily newspaper and making himself available to student sojourners who would stop to chat. He welcomed former students on football weekends and could be found outside the stadium before the game dressed in a suit and tie, a tall, commanding presence savoring a hot dog. After the game he’d greet visitors in his Maritain Center office (the location he noted well: “Room 714, Memorial Library”). He’d be sitting behind his desk, enveloped in cigar smoke.

Evans had a knack for remembering the names and details of his former students. As we savored memories during a game-day visit in his office, he turned with a grin to my wife, Rita, and asked, “And how is Ed?” (Rita’s brother Ed Orlowski ’72 had also had the pleasure of taking Evans’ course.) A few years later, after our old professor’s death, another former student of his, Gus Zuehlke ’80, wrote in the Scholastic about Evans’ remarkable gift for remembering names, suggesting it pointed to something far deeper. “He was a personalist — a follower of Catholic thought that centers on the infinite worth of the human person, including the eternal soul,” Zuehlke wrote. “He wanted to address our souls as eternal beings.”

Even in the everyday, Evans sought eternity. In “A Walk Across Campus,” an essay he published in the November 4, 1977, issue of Scholastic, he chronicled what for him was a regular sojourn from his office on the “Philosophers’ Floor” of the library to the “Caf,” then the public portion of the South Dining Hall, where he’d meet with students or colleagues and feast on “transcendentals” and “victuals.” Along the way, he would pause at the crossroads south of LaFortune, the site of the original memorial in his name.

His thoughtful, deliberate speech in the classroom allowed for meticulous notetaking. Reviewing my notebook from that course, I came across a highlighted discussion about Pope John XXIII, whom Evans loved. “He really knows how to Pope!” he once said, a comment that I suspect reflected his admiration of the Holy Father’s compassionate persona more than any assessment of his doctrinal proclamations.

In the class just before spring break, after an eloquent reading of Hopkins’ poetry, Evans commissioned us to return home for the holiday and “have a good read . . . and a good feed.” It seemed like more than a clever farewell, rather a reminder to nourish our minds, bodies and souls — the whole person.

Such are my recollections of this brilliant, kind and welcoming man. I feel blessed to have known him. As his profile in the 1969 Dome points out, he was “a man to be experienced as much as he is a man from whom one learns.”

Evans’ words and presence taught us the essence of “seeing the world in a grain of sand and heaven in a wildflower.” During a 1974 visit in his library office, we introduced him to our newborn daughter, Renée. Joe presented her with her own copy of The Little Prince. His note inside the front cover read, “Renée, welcome to the planet. I wanted you to have your own personal copy of this book, a real matter of consequence. Joe Evans.” Renée ’96, ’00M.Div. is now a senior writer and digital program manager for the Keough School of Global Affairs. She and her children still treasure her copy of the book, its binding broken and its pages yellowed.

In our copy of The Little Prince, also inscribed with a note from Evans, is a reminder from Saint-Exupéry that “what is essential is invisible to the eye. It is only with the heart that one can see.” For our last day of class, dated Friday, May 22, 1970, in my spiral notebook, my final note of Evans’ words reads: “Every teacher ought to be able to point to the world in a grain of sand.”

Allan R. LaReau is a retired pediatrician from Kalamazoo, Michigan. He is a survivor of Emil T. Hofman’s General Chemistry course and was part of three team trips to Léogâne, Haiti, as part of Emil’s Army.