“Marley was dead: to begin with.” So begins Charles Dickens’s classic Christmas novella, A Christmas Carol. Because the story is a classic, we rarely stop to think much about lines like that one. Merry balls and plum puddings notwithstanding, the book can be a bit morbid. It asks us to think about how the deaths of others — like Scrooge’s dead partner, Marley — should change the way we measure our lives and our work. Dickens himself was aware that his “Ghostly little book” was a bit incongruous with the cheer of Christmastide, and he hoped it would not “put my readers out of humor with themselves, with each other, with the season, or with me.”

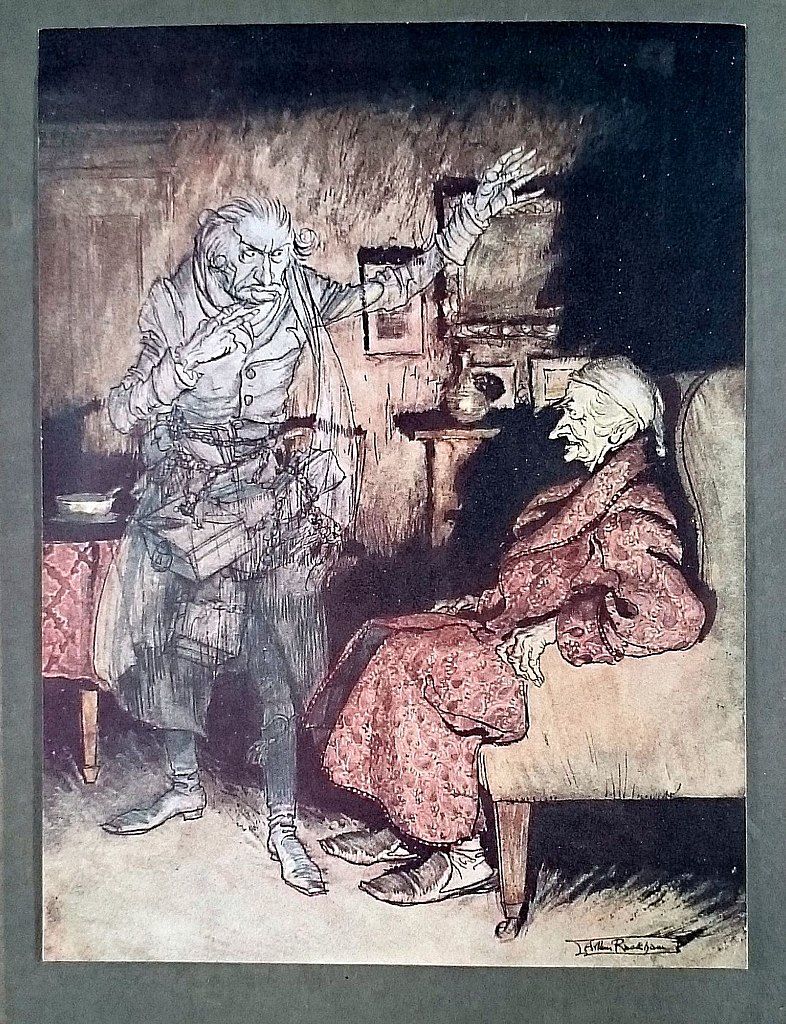

Of course, the story isn’t simply chilling; it’s about a hard-won change of heart. When Marley’s ghost tells Scrooge about the heavy chain he carries that was forged in his lifetime of ruthless business dealings, at first Scrooge protests, “But you were always a good man of business, Jacob,” he insists. But the Ghost replies, taking back the term: “Business? . . . Mankind was my business. The common welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence, were, all my business. The dealings of my trade were but a drop of water in the comprehensive ocean of my business!”

For Scrooge to finally get the message, he has to encounter not just his dead partner, but his own mortality. He hovers near his funeral and corpse and finally comes face to face with his tombstone.

In short, it’s a fanciful tale with a moral that is, pardon the expression, dead serious: Merry Christmas, and memento mori. Add to your experience of A Christmas Carol this year the knowledge that, although the story of Scrooge never happened, it happens.

Craig Crossland, the Rev. Basil Moreau, C.S.C. associate professor at Notre Dame’s Mendoza College of Business, recently brought a scientific approach to Scrooge-like scenarios in modern corporate management. Along with Guoli Chen (INSEAD) and Sterling Huang (Singapore Management University), Crossland observed what happens to CEOs when a close business partner — in this case a member of the board of directors at their company — dies. Their research, in press at Management Science, is called “That Could Have Been Me: Director Deaths, CEO Mortality Salience, and Corporate Prosocial Behavior.” It suggests that some of Dickens’s insights hold up remarkably well.

Crossland and his colleagues conducted their research by focusing on 89 CEOs who experienced the death of a director between 1990 and 2013. All were CEOs of large, publicly-owned companies where Crossland and his colleagues could gather data about the firm’s socially responsible activities. Crossland and his team also matched each company with another that did not lose one of its directors during the same time period.

When the researchers set out, their main inspiration was not Scrooge but rather Terror Management Theory (TMT), a field of psychology that considers how our awareness of our mortality shapes our behaviors. They hypothesized that the death of the director would cause the CEO to reflect on his or her own mortality. This reflection, they believed, would cause the CEO to draw closer to other people, connect with them more deeply and seek to help them in meaningful ways. Ultimately, they believed the effects would show up in the company itself as the CEO pushed not just to make a profit but also to consider people and the planet as well.

They were then able to track what happened at the company for the next four years. They looked at six dimensions of corporate social responsibility: community relations, diversity, employee relations, environment, human rights and product quality. After observing the four-year period that followed the director’s death in each company, Crossland and his colleagues were able to prove their hypothesis correct. Director deaths really did result in a greater emphasis on corporate social responsibility within the companies they left behind. And this appeared to be mostly a result of the CEO’s change of heart. When CEOs identified closely with the dead director, the effect was even more robust.

Of course, waiting for something as traumatic as the loss of a close business partner is not a reliable way to become a better person. The moral of the story — and the psychology, for that matter — is that we should not wait. We can become a little less Scrooge-like now by bringing our awareness of our mortality up from the subconscious depths where we most often attempt to suppress it.

A time-honored strategy recommended by ethicists is the practice of imagining your own funeral, much in the way Scrooge is forced to do. And for those of us who feel lacking in imagination, a little fiction can’t hurt.

Brett Beasley is the associate director of the Notre Dame Deloitte Center for Ethical Leadership.