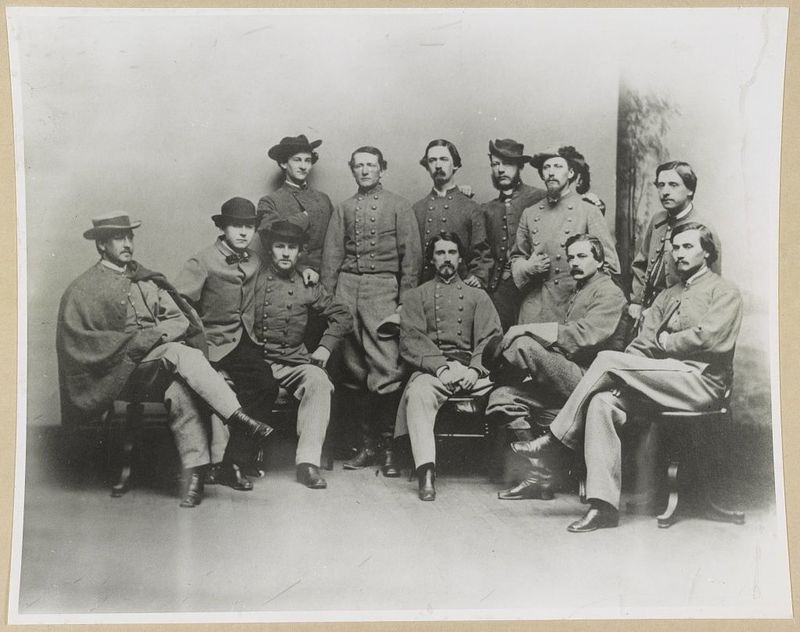

Colonel John Singleton Mosby and some members of Mosby’s Rangers, 43rd Virginia Cavalry Battalion. Library of Congress

Colonel John Singleton Mosby and some members of Mosby’s Rangers, 43rd Virginia Cavalry Battalion. Library of Congress

When I was a boy growing up in Louisiana in the 1950s, I was steeped in the marinades of the Old South. My bookshelves were stuffed with accounts of the Civil War. Thick picture books lit my imagination with paintings of battle action and blood and valiant warriors on horses. I absorbed the legends of Jeb Stuart, Stonewall Jackson, Robert E. Lee and “The Gray Ghost,” Colonel John Singleton Mosby. I had a big, life-size Confederate flag. My great-great-grandfather, William Jesse Anderson, was killed at the battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas. I have a letter written by him a few days before he died. I was a Child of the Confederacy, with a certificate to prove it.

Gone with the Wind was considered the great American novel. On cold or rainy days I arranged dozens of wagons, cannons, horses and little soldiers — uniformed in grey and blue — in elaborate battle scenes of clashing miniature armies. Statues of Confederate heroes stood on the oak-draped lawn of the local courthouse. I echoed the mantra: “The South shall rise again.” My parents taught me to stand up when I heard “Dixie” playing. And we did, in bingo halls and restaurants, whenever that rousing or melancholy anthem was played. Sometimes we sang along. “I wish I was in Dixie . . . look away, Dixieland.”

We made family trips to the battle museum in Mansfield, Louisiana, and to the expansive battlefield on the steep bluffs of Vicksburg, Mississippi, where Rebel soldiers were locked under siege by Yankee forces for more than 40 days. Beleaguered but unbowed, they were forced to eat their own horses. Their eventual surrender marked the beginning of the end of the War Between the States.

William Tecumseh Sherman was a Yankee general and an evil man — the father of modern warfare, mastermind behind the initial “scorched earth” strategy. His troops burned, looted, pillaged and devastated the South on their way to the burning of Atlanta.

As a boy growing up in the South, I was told the War for Southern Independence was about states’ rights. It was about not letting outsiders tell you what to do. Protecting a way of life. The Rebels were brave, defiant, gallant. They were ill-outfitted underdogs fighting the leviathan forces of the bloodless, industrialized, heavily equipped Union soldiers from the North. The Rebels, I was told, fought to the end because they were defending a cultured lifestyle. The Yankees were mercenaries from big cities and factories dispatched to subdue and ravage Southern homelands.

When I first asked if slavery had not been the real reason for the rebellion, the answer came back again: state’s rights, to preserve the natural order of things, to protect personal freedoms, the right to choose — apart from meddling government control. Most slaves were happy and well cared for, I was told, when I asked a second time. And, anyway, the South was intending to end slavery, in due course, but it couldn’t just happen overnight. It took time to change a society built on slave labor without causing a total collapse — which wouldn’t be good for “them” or “us.”

When I was a little boy, I half accepted these explanations. I didn’t know better. My parents told me so and everything around me confirmed these cultural beliefs. Segregated schools and separate water fountains and “colored people” not allowed in white restaurants were all accepted customs. And, back then, most folks wanted to keep it that way. They didn’t like change, and they felt threatened by those upsetting the system. Even many righteous religious people preached preservation of the status quo over the disruptive examination of conscience that bold marchers were calling for.

Power is a hard thing to let go of.

This is the lens through which I have watched statues of Confederate heroes coming down and Black Lives Matter protesters taking to the streets and others holding tight against social tides and vowing to maintain law and order while stoking the fires of division, hatred and fear.

There are many themes to explore here — all now part of a national conversation at a time of critical promise and peril. But my childhood leaves me with another lesson, too.

Like everyone else, I am the product of a time and place. I absorbed what my parents taught me, what my surroundings showed me. I was a believer. I knew what was true because pretty much all I read or heard or saw reinforced the prevalent thinking of that time and place — the loyalties and prejudices, the myopic perspective and steadfast resolve to stand in place. My parents, too, were shaped by the society, teachings and conventional wisdom of their world.

In time, of course, my horizons expanded. I ventured to the other side of the levees that kept two worlds apart. I read other books and traveled farther and talked to people unlike me and went 1,000 miles north to get a college education. I have lived another 50 years since leaving home, but the enculturation I received back then is very much a part of me still. My sensitivities and understanding, though, have been transformed since I was a boy in a pocket of the world clinging to haunted myths.

But I read another lesson in these memories beyond the complexities of America’s racist past, and present. The irony and the tragedy is that today — when immediate global communication and migration are dissolving the geographic borders dividing us — we are returning to factions and tribes, clans and camps.

One of the great dangers facing us today is our fragmentation, our aligning with like-minded people and demonizing the other. Equally dangerous is the splintering of our news sources, the proliferation of pretend news and fake news, the silos in which we live today — as we follow only those news sources that merely reaffirm our own thinking. There is danger in watching those “news” networks that claim to inform while their real intent is to influence, indoctrinate and promote a political agenda that favors hostile fireworks over truth. Or to traffic in social media that inflames without any test of credibility.

When I look back at my childhood, I recognize the unsettling resonances between then and now. I also see the boy who embraced a misguided mythology because he was immersed in its tenets and hadn’t yet ventured beyond what he knew and believed — because then it was all so black and white.

The lesson here is the importance of listening and watching and reading beyond our own confinements. It is both more and less than following the advice to walk a mile in another’s shoes. It is simply to listen to other voices, to question the veracity of your own sources, to seek the other side of the story, to know there’s usually more here than meets the eye. And to be open to opening your mind.

The world comes in many shades of grey. To think otherwise is akin to living in an insular and impoverished place.

Kerry Temple is editor of this magazine.