It would be easy to tune out the stained-glass windows of the Basilica of the Sacred Heart as Catholics too often tune out the readings at Sunday Mass, the opportunity for grace and insight lost with the careless notion that we’ve seen or heard it all before. Just so many gem-toned depictions of halos gazing heavenward, saints whose holy lives and contributions we think we know, and no noteworthy difference between the artistry found in Notre Dame’s centerpiece church and what you’d find in thousands of Gothic naves and transepts from here to Paris to Vladivostok.

Look again. And do so with the learned assistance of Stories in Light: A Guide to the Stained Glass of the Basilica at the University of Notre Dame, released in March by the University of Notre Dame Press. Local scholars Cecilia Davis Cunningham and Nancy Cavadini draw upon their respective backgrounds in art history and theology to tell the story of one of the basilica’s true artistic treasures — and the many stories it contains — illuminating the ties between the founding of the University and the revival of a sacred art form that the authors say is both quintessentially religious and French to the depths of its soul.

The tale they relate in the introduction to their comfortably sized guidebook begins in the empty pockets of the Congregation of Holy Cross, which couldn’t afford to buy stained glass for the church it was building in Le Mans, France, in the 1840s. So the priests and brothers did it themselves, and when their close friends and neighbors the Carmelite nuns of Le Mans faced the same difficulty, they followed the men’s modestly successful example.

How the women managed to create one of 19th-century France’s most prolific and sophisticated glassmaking studios while maintaining the integrity of their cloister remains a mystery, but, true to their vows, they kept their piety intact and their prices low. Over 50 years, the reputation of the Carmel du Mans Glassworks and the many craftsmen it employed spread, and its product — thanks to the good taste of Father Edward Sorin, CSC, and many, many others — may today be found all over France and as far away as Japan and northern Indiana.

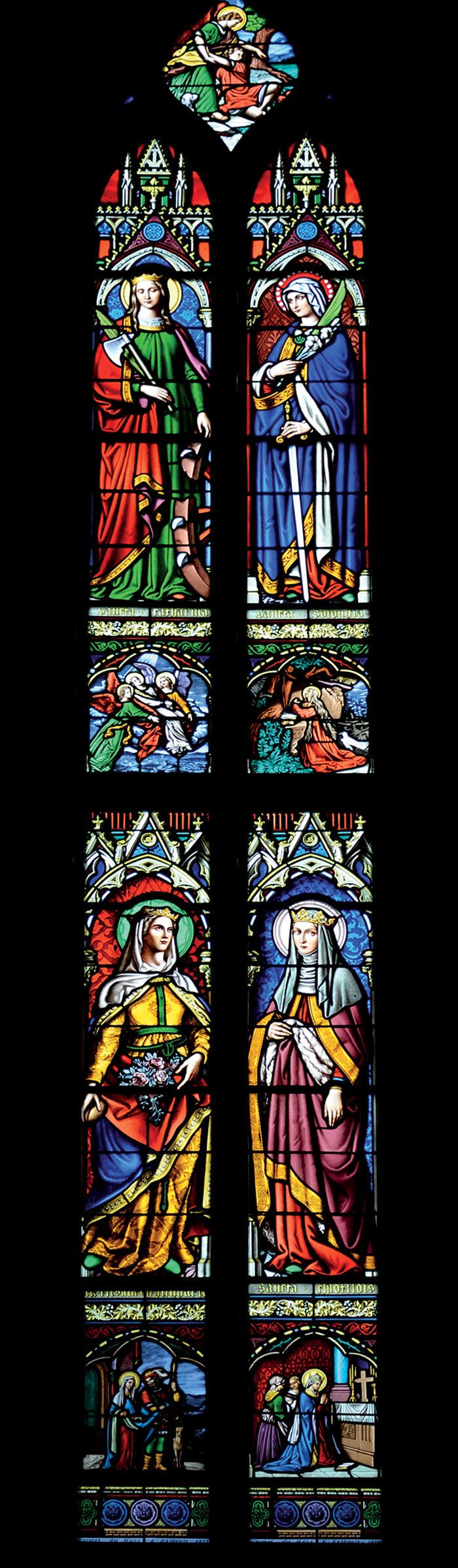

Walking from the main doors to the Lady Chapel, a visitor can get — in 220 individual scenes, read left to right, low to high — a coherent meditation on the mercy of God, another on the lives of saints, a third on the Church itself and yet another on devotions important to the congregation. “Notre Dame’s windows reveal the world of its founders in all its richness and complexity,” Cunningham and Cavadini write. “Fr. Sorin was certain that the French Catholic faith he brought with his fellow religious would provide Indiana with the religion, education, and culture it needed.”Sorin bought three of the Carmelites’ windows for Notre Dame’s original Sacred Heart Church and, in 1870, ordered some 450 square meters of brightly colored theological eloquence, a project so large that, in the words of one proprietor after the nuns sold the business in 1873, Notre Dame got that rare result: “a church [with stained glass] that makes sense.”

Stories in Light translates that complex, beautiful message for the modern reader — Father Sorin’s last and best homily, a gift enduring into the 21st century.

John Nagy is managing editor of this magazine.