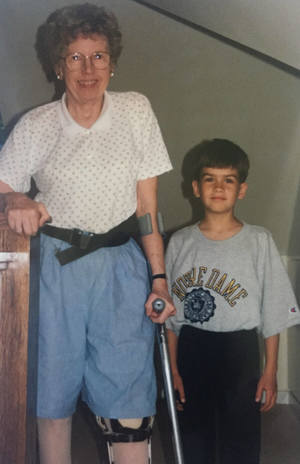

A polio infection as a young mother affected Kathleen Baugh Gleason and her family for decades. Photos provided.

A polio infection as a young mother affected Kathleen Baugh Gleason and her family for decades. Photos provided.

I stared hard at the gray-haired women as they stared at my mom. It was 1958, and we were at Wyatt’s Cafeteria in Dallas. I carried a tray, as did my dad. Servers carried trays for my two younger brothers and Mom, as she was on crutches and six or seven months pregnant.

We ate Swiss steak, my favorite, plus sweet corn and mashed potatoes. Chocolate pie for dessert. Eight-year-old heaven.

When it was time to go, Mom slipped into her wooden crutches and rose up. The women stared again.

As Mom, Dad and my brothers headed toward the door, I dawdled. Then, leaning about a foot from the women, I burst out, “It’s not polite to stare!” — and ran.

For the rest of my childhood, indeed well into high school and maybe even into adulthood, I hurled fierce, obsidian black stares at anyone who dared to stare at Mom. Ferocity depended on how ornery I felt, but I think folks got my message.

Four years before that cafeteria dinner, Mom had had a bad case of polio — it nearly killed her — but I wanted her and our family to be as normal as any other. After 70 years of widespread polio epidemics, some 60 million would wind up with some form of paralysis.

Kids and grownups in the United States had rolled up their sleeves for the Salk vaccine or swallowed the Sabin vaccine. There were still plenty of places around the world where polio was ruining lives, but America had dealt a blow to the virus and the mood of the country was to move on, says Harvard professor Marc Shell in his book Polio and Its Aftermath.

But plenty of people, including my mom, Kathleen Baugh Gleason, had become long-haulers. Polio shaped the rest of her life — and those of her family members.

Post-polio people were often stared at, or worse, shunned. Shell knows firsthand, as he had polio in 1953 at the age of 6. After the vaccine, Shell says, people in wheelchairs and on crutches or in braces were visible evidence of a painful time in America. The country wanted instead to focus on fighting the Cold War and getting that man to the moon.

Shell worries that America will develop the same sort of amnesia today. A White House ceremony marking 500,000 COVID-19 deaths commemorated the pandemic’s toll, but once herd immunity sets in, will the country leave the long-haulers behind?

Mom did physical therapy for years. At the beginning, she swam at the YWCA pool, and I was carted along. It was a swell deal: an Olympic-size pool, egg salad at the cafeteria and a break from my pesky brothers. Mom sometimes visited with Judge Sarah T. Hughes as they worked out. The same judge who administered the presidential oath to Lyndon B. Johnson.

My job was to stretch Mom’s muscles. I did my best but wonder how much stretching a 5- or 6-year-old could do. Maybe Mom took me because it was good for a child who, even at that age, had made books her permanent residence.

Later, when I was a Brownie Scout, Mom climbed 15 steep stairs to the Scout House to witness my “fly up” to cadethood. Her climb took at least 20 minutes — and then there was the perilous trip back down — but she was determined.

A number of times when I was a kid, Mom spent several weeks in a hospital rehab unit: intensive physical therapy not available in our small north Texas town. Years later, my brother Dan told me that she also got intensive treatment for depression.

Mom gradually developed post-polio syndrome, which meant recurring pain, chronic fatigue, susceptibility to infections and recurring depression. The syndrome never went away; it only got worse.

Long-haul COVID-19 survivors have some of those same symptoms as well as others: fevers, chest aches, shooting pain, stroke, kidney damage and inflammation of the heart, to name a few.

Such survivors are organizing and making their voices heard, but Shell says they may nevertheless face suspicions about malingering, or not be taken seriously because they aren’t in wheelchairs or wearing braces. Their symptoms aren’t readily obvious, may not lend themselves to measurement (aches, fatigue, brain fog) and may be protean. Also, physicians don’t have ready answers for treating long-haul patients.

By the 1960s, Mom had graduated from a wooden wheelchair to a metal one that folded neat as a napkin. As her daily tool, it went with her on trips, but she wouldn’t have it subjected to indignities of the baggage compartment. “I’m sorry,” the airline desk clerk would say. “The first-class closet is for jackets and coats.” Never mind that Mom traveled coach; she was quite certain the chair had to go in the closet. As a college kid, I could drink a whole cup of coffee while Mom worked on the clerk. The chair always went first class.

On a 1972 trip to New York, Mom worked a similar play at the Guggenheim Museum. Forget the Picassos and Kandinskys: Mom whizzed the continuous, multi-level spiral gallery from top to bottom, waving to guards along the way. Initially dumbfounded, they eventually waved back and onlookers cheered. A huge huzzah greeted Mom at the bottom.

Maybe it was about her shoes: Pre-polio, Mom had loved fancy heels. After, she wore ugly oxfords and a heavy brace that secured at her left ankle, knee and upper thigh. But as post-polio syndrome set in and that leg gradually lost what little strength it had, we grieved. With the brace and oxfords gone, however, Mom started wearing sophisticated flats, including Ferragamo’s, preferably procured on sale.

By the time my sons, Sean and Brendan, were 6 and 9, Mom used her wheelchair most of the time; post-polio syndrome continued wreaking damage and, despite PT, she had many days and nights of aching muscles.

One summer evening, Mom watched Sean and Brendan zap a hockey puck around our basketball half-court. Suddenly, Sean was at the back door: “Mom, you better come. Gramma’s gotten hurt.”

Invited to join the game, she’d eventually taken a puck in the right shin. The hematoma was, well, the size of a puck and getting bigger by the minute.

I roared, “What were you three thinking?! Didn’t you know Gramma might get hurt?” Muttering about car keys and the ER, I turned back toward the house. Sean then turned to Mom: “Jeez, you’re pretty good for a gramma.”

By the time great-grandchildren came along, Mom’s days as a hockey player were long over. But all of us knew GG (Great Grandmother) would read aloud for hours on end. For little ones, pushing her latest wheelchair (titanium, not 100 pounds of wood) was the best game in town.

All this makes me think people suffering from long-haul COVID-19 may have to be tough like my mom — and it won’t be a game.

Cathy O’Donnell was a reporter for The Ann Arbor News. She is now retired and living in Seattle.