Illustration by Blair Thornley

Illustration by Blair Thornley

- 10th Annual Young Alumni Essay Contest

- Schaal Prize: “Forecast," Beth Spesia Muench ’15

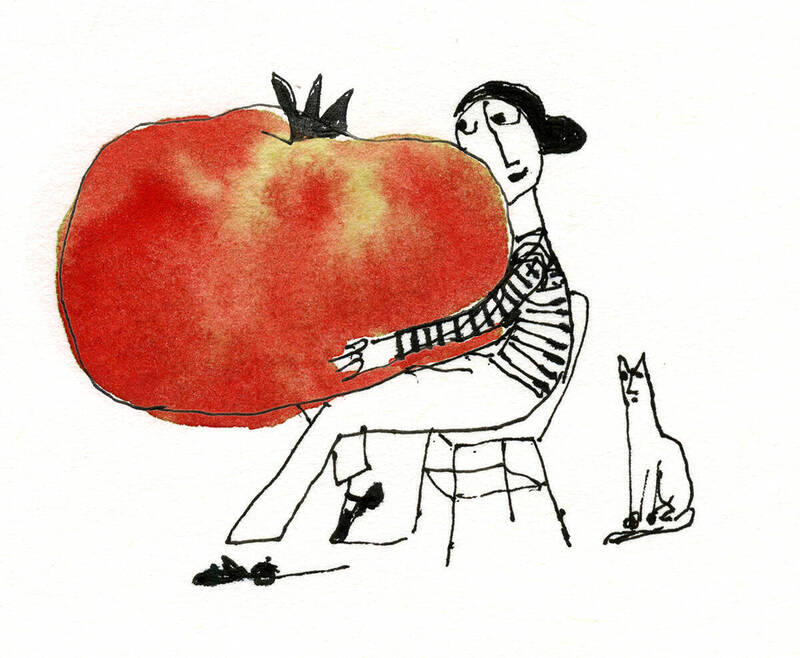

- 2nd Place: “Tomato Season," Megan Valley ’18

- 2nd Place: “The View from Apartment 206," Amy Teske ’19

- Honorable Mention: “Joyful Mysteries," Mary-Kate Burns Corry ’16

- Honorable Mention: “Subjective Cycle of Disturbance,” Jacqueline Cassidy '15, '16MSM

- Honorable Mention: “Call Time,” Gretchen Hopkirk ’20

- Honorable Mention: “The Southern Tragedy,” Catherine Truluck ’20

- Honorable Mention: “Empty on Purpose,” Natalia Yepez Frias ’19

I moved to Pittsburgh the first week of August, nearly a month before my classes started. I wasn’t working; I wasn’t doing much of anything besides relearning how to read, watching horror movies and laying in front of a fan with my cat in our basement apartment. It’s easy to forget you’re actually, physically real in such a state of being, so I needed to find a justification for my existence, something to push me through the most stifling month of the year. Thankfully, it was tomato season.

Whatever happened to tomato-season fever? Only a few summers ago, everyone was performatively pining over tomato season, even (especially) in the midst of it. Tomatoes, vaguely Mediterranean and chic in that there are any number of heirloom varieties that aren’t as readily available for most other vegetables, were then described as a symbol of hope, perseverance and wonder among other things in the multitude of online publications I read that summer — and I did read all of them.

Posting photos of an heirloom that year marked you as the sort of person who dedicated weekend mornings to a farmers market, which is a status symbol among a certain cohort. It means you probably meditate and journal and listen to highbrow podcasts on your commute, too. Even as the final days and hours of tomato season lingered and the air threatened to crisp up, tomato season was still being memorialized on the internet, whether in listicles of tomato tweets or quaint news stories about the hardy plant growing in an unexpected place.

And then tomato season ended. When it returned approximately 46 weeks later, it didn’t receive a welcome matching the vigor it had temporarily retired with. Perhaps the pandemic had embittered our fancy; maybe the tomatoes were mealy that year. But while everyone else has moved on to other frivolities, my feet remain firmly planted. I am never leaving tomato season.

Few things sting more than the unfulfilled promise of a photogenic tomato someone else is showing off. It’s so much worse than the acidic juice dripping down your sunburnt or mosquito bite-riddled forearms. When I think of tomato season, what springs to mind is a post by one of my favorite magazine writers — a picture of a salted black velvet tomato slice that still makes my mouth water three years later. The flesh was so dark and opaque that, without the scattered pockets of seeds, it might have been mistaken for meat. But try as I might, I’ve never found a truly beautiful heirloom tomato myself.

Even before this past summer, I’d searched high and low for the best produce, tomatoes included, in regional grocery chains like Hy-Vee and Schnucks, big-box stores like Walmart and Meijer, the Trader Joe’s, Whole Foods and Fresh Thymes, specialty stores and ethnic grocers and, of course, farmers markets. And still I’ve never found the gorgeous heirloom tomato I feel has been promised me. It’s not that I’m picky — I eat the bad ones, too, the pale, limp, hydroponic atrocities that look and taste like the ghost of a ghost of a tomato. They’re anemic and watery and found year-round on fast-food burgers and in chopped diner salads, and I like them just fine.

There’s no real reason, sentimental or otherwise, for my tomato obsession: no passed-down family recipes, no childhood memories of a sprawling backyard garden. My parents bought and served us the same Roma and beefsteak tomatoes from the grocery store year-round, the same canned pasta sauces as anybody else. I don’t remember when sun-dried tomatoes came into our family diet, but it wasn’t an earth-shifting moment. The other vegetables I eat most often — broccoli, beets, Brussels sprouts, lacinato kale, shallots — are best within their proper seasons, too, but my palate is not nearly as sensitive to the discrepancies among them in and out of season, and their seasons are not quite so fleeting. Besides, no one I know is buying heirloom broccoli — it simply isn’t as glamorous.

Last summer, I was determined to be successful in my hunt. I had all the time in the world and limited funds to pursue much else. The first time I went to my neighborhood’s Sunday market, I bought a pint of orange, candy-sweet Zimas mixed with a few red-brown ones. The skin had splotches of a nearly purple hue spreading like a bruise from the stem. I popped these little flavor sachets two or three at a time over the course of a few hours, and then they were gone. They were quite good, but not big enough to fulfill my arbitrary qualifications. Meanwhile, the larger pink tomato I stupidly paid $3 for was underwhelming and couldn’t stand up to any of the other ingredients in the niçoise salad I made, not even the blanched green beans.

The basket of heirloom tomatoes at most chain grocery stores always strikes me as silly if not perverse. It is even less the fruit of one’s own labor than buying from a market, and they almost always have dry brown cracks haloing either end or a questionable hole with ragged edges right in the middle. Still, I bought a few. One was the same color as jammy, soft-boiled egg yolks, and it was remarkable, the best I’d eaten at that point in the season. When my parents came to drop off the things that would fill my apartment, they took me grocery shopping and, a little embarrassed about my new mission, I picked up a pint of normal, cheap grape tomatoes that were perfectly adequate — and obviously disqualified from competition.

The last tomatoes I bought before my classes started were the most striking. My roommate and I, no longer strangers, went to a nearby neighborhood market. I bought two tomatoes slightly bigger than camparis, and the skin was rippled with stripes of green and yellow. They weren’t unripe, they just looked like they were. The insides were kiwi-bright and the seeds contained an excess of that gelatinous goop; they looked like tropical fruits or something more alien. They weren’t terribly sweet but had a mellow earthiness I liked, and I was content to end the competition there and crown a winner.

Tomato season closed less than a month after my classes began. I gorged myself on them until then: sliced thin with mayonnaise on cheap white bread, blistered in a skillet with some tinned fish for a pasta sauce, chopped in salads, eaten in wedges with salt and pepper. And then tomato season ended and my classes did not and I kept on just the same.

Megan Valley’s essay was one of two second-place winners in this magazine’s 10th annual Young Alumni Essay Contest. A writer and journalist, Valley is a first-year candidate in the University of Pittsburgh’s graduate program in nonfiction writing.