One bright August day in 1964, when I was 5, my mother and I boarded a Pan American 707 jet clipper and flew halfway around the world. Our flight winged us from Tehran to New York with stops in Ankara, Zurich and Paris. Our need was urgent, and the airline lived up to founder Juan Trippe’s boast that his carrier would be “the chosen instrument” of American prestige. He kept his promise.

For decades Pan Am ranked as the world’s best airline. I flew PA 001, one of its two daily round-the-world flights. One went east, the other west, linking the great cities of the world, a service Pan Am began in 1947 — and a feat no other airline matched for decades. Pan Am was the first to offer transpacific (1936) and transatlantic flights (1939), the first to fly 707s across the Atlantic (1958) and first to fly 747s (1970). It had the first global computer reservation system (1962). Such was the airline’s renown that when a Pan Am spaceplane soared to “The Blue Danube” waltz in 1968’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, 93,000 people made reservations for future moon service.

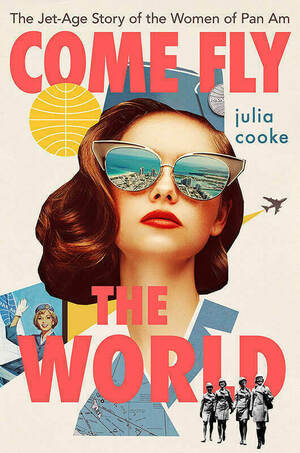

“Pan Am was the American flag, for all practical purposes an extension of the U.S. government. Even before there was Coca-Cola in some places, there was Pan Am,” says a CIA officer quoted in Julia Cooke’s Come Fly The World: The Jet-Age Story of the Women of Pan Am. Cooke, the daughter of a Pan Am executive, weaves together stories of adventure-seeking young women from small towns. She gives surprising emphasis to gut-wrenching accounts of Pan Am’s role jetting soldiers on R&R leave out of Vietnam and its mercy mission flights that took orphans to freedom in 1975.

In the world of geopolitics, Pan Am became a chosen instrument for the national interest. For stewardesses, however, the airline was “the instrument of [their] own freedom,” Cooke writes. Globetrotting meant shopping in “Italy for leather shoes, Paris for hose, Beirut for jewelry,” dining on Caesar salad and red wine at Bernard’s in Hong Kong, skinny dipping in Monrovia, Liberia, and getting movie star service at Beirut’s InterContinental Phoenicia Hotel.

“To know the door code for the after-hours club where you could dance until the sun’s light dimmed the glowing neon bar signs outside, to luxuriate in the company and the cocktails and the feeling of a young body, alive and all yours moving passionately — that was the life they sought,” says Cooke. To be sure, her account of stewardesses’ lives contains no tales of bedroom frolic from Djakarta to Jamaica. (Well, one did drench herself in red wine in a Monrovia hotel room and made a print of her silhouette on the wall, but that’s about it.)

In prior decades, young American men had been free to answer the call of “Go west, young man.” Now thanks to Pam Am’s global destinations (more than 80 in 1968), restless women from places like Whittier, California, and Baldwinsville, New York, could do the same. “There’s a whole world out there, and I need to get involved,” thought future stewardess Lynne Totten, who felt trapped in a biology lab analyzing the pollen in 100-year-old soil samples. “Life is too short to waste even one precious year on dullness,” mused another.

These young women were smart, talented — and lucky — and they knew it. During training classes, instructors drilled into future flying attendants a definitive idea: You are an ambassador of the United States of America. Pan Am only accepted three to five percent of stewardess applicants. In the 1960s, 10 percent of its flight attendants had attended graduate school at a time when fewer than 10 percent of American women went to college. They also had to speak a second language and stand between 5’3” and 5’9”, be under 26 when hired, and weigh between 105 and 140 pounds.

“Pan Am’s goal for its stewardesses was femininity and sophistication that stopped short of sexual availability; they were to be clean, pretty, ladylike, and uniform, their every angle enforcing corporate identity,” writes Cooke. Like flight attendants on other airlines, “when they were working, their self-presentation, from hemlines to hats — and the way they applied makeup, when they smiled, what they said — served the corporations, the men who ran them, and the men they sought as paying customers. The women were more or less willing to go along with such visible constraints to earn so much autonomy.”

The glamour of global travel evaporates when she recounts the stewardesses’ Vietnam experiences on flights in and out of that country during the war. Pan Am used 12 percent of its fleet to fly — at first for free and then at cost — more than 375,000 men on R&R flights to Toyko and Hong Kong. Grimy soldiers barely out of high school clad in “dank and dusty fatigues” boarded straight from the field, their boots caked with red clay. “These men looked like ghosts, like dead men, each with that 1,000-yard stare,” writes Cooke.

Stewardesses on those routes saw mortars firing and napalm dropping. Bullets hit their planes. No wonder the military designated all women on such flights second lieutenants and had them carry Geneva Convention ID cards in case they were captured.

On a flight over the Pacific the day of the first moon landing in 1969, all 164 Vietnam-bound Marines stood to sing every patriotic song they knew. When a stewardess walked down the aisle, “she saw the tears on the men’s faces. They were heading to someplace they had probably never heard of, she thought, to die for a confusing, likely doomed cause, and still, they had stood up to sing about America.”

At the war’s end, Pan Am and other airlines flew out refugees. One stewardess recalls a horror flight from Da Nang. In scenes that for many readers will evoke events at Kabul’s airport in 2021, the CBS Evening News filmed crowds flooding the runway. As the 727 sped along, terror-crazed Vietnamese enlisted men clawed each other trying to climb its rear ramp. On takeoff, a grenade exploded under a wing, shaking the aircraft. Bullets ripped a fuel line. Bodies fell from wheel wells.

Aloft, a stewardess tied a towel around a man’s waist — his intestines were spilling out. She collected guns, grenades, and ammo as though she were picking up cups and napkins. Safely at a hotel, she closed her eyes to sleep, but in her mind saw bodies “splayed and broken.” Of that flight’s 268 passengers, five were women and two or three were children. The rest were soldiers.

Later, a Pan Am 747 evacuated hundreds of orphaned infants and children from Saigon. “The din and the scent of the frightened children was unbelievable,” Cooke writes. “The scope of the present disaster — the fear that could drive a mother to hand her infant over to an unknown future — overwhelmed” one stewardess. “Empathy became anger as she moved down the aisle. What the hell did we do to these mothers that they’re sending their babies away? she thought.”

I can’t pretend to know what that hell was like, but I have known my own, and Pan Am flew me to safety, too. My family lived in Ahwaz, Iran, in the early 1960s. When I injured my eyes, local doctors had no treatment plan. In the examining room of the best ophthalmologist in Tehran, I heard him tell my father he wanted to operate.

“No,” my father said. I cowered behind him holding the leg of his khaki pants. Then he added — “George and his mother are flying to America tomorrow.”

I wore dark glasses that day. In the cloudless sky I looked out the window down at the glittering Atlantic. “Everything’s going to be OK,” I thought. “I’m going to America.” In some way, I, too, was an immigrant to the New World, the place where dreams come true. For me, they did, and for that I thank my parents, my American doctor, and Pan American World Airways.

And its stewardesses.

George Spencer is a freelance writer who lives in Hillsborough, North Carolina.