After the death of Blessed Brother Andre Bessette, CSC, in 1937, Catholics removed his heart and placed it in Saint Joseph’s Oratory, a large church in Montreal founded by Brother Andre.

The mysteriously non-decomposed body of Saint Bernadette, who told of being visited by the Blessed Virgin at Lourdes in the 19th century, lies in a glass tomb in Nevers, France. A finger believed to be the one that doubting Saint Thomas stuck in Jesus’ wounds is on display at the Church of the Holy Cross of Jerusalem in Rome. These historical keepsakes belong to a category of revered objects known collectively in the Roman Catholic Church as relics, visual reminders of the saints. The Basilica of the Sacred Heart has its own large collection of them, including items believed to have come from each of the 12 Apostles and from the manger at Bethlehem, pieces of the veil and girdle of the Blessed Virgin and a splinter of the True Cross. Just as Catholics do not worship saints but rather venerate them as role models and ask them to offer prayers to God, relics are not worshiped or believed to hold any special powers.They serve as reminders of the lives of the saints and their sacrifices for Christianity.

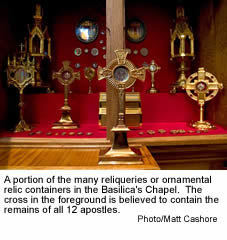

Relics are defined as the material remains of canonized and beatified saints. Some are bodily remains, such as a hair follicle or small bone. Others may strike us today as somewhat gruesome, like the two heads in Saint John Lateran Basilica in Rome believed to be those of the apostles Peter and Paul. The Basilica of Saint Anthony in Padua, Italy, displays what is thought to be Anthony’s tongue and jawbone. Objects believed to have been used during a saint’s lifetime or that touched their material remains also qualify as relics, but bones and flesh are considered the most sacred. Most of Notre Dame’s collection is housed in the Basilica’s reliquary chapel near a wax figure of Saint Severa, martyred for converting to Christianity in the 7th century. Cloth-covered lead boxes at the figure’s head and feet are said to contain her bones. It is traditional to place bones of saints in a case beneath the altar of a Catholic church as a reminder of Christ’s sacrifice and of those who sacrificed their lives for Christianity, says Father Peter Rocca, CSC, ‘70, ’73M.A., rector of the Basilica. Bones beneath the Basilica’s main altar are said to belong to Saint Marcellus, a third-century centurion beheaded for refusing to serve in the Roman army. Rocca believes most of Notre Dame’s relics were gifts to Notre Dame’s founder, Father Edward Sorin, CSC, from visiting bishops. Sorin also may have acquired some on his frequent trips to Rome, says John Zack, acting University sacristan. The use of relics emerged when people began honoring saints and martyrs in the early church. Christians would celebrate a saint’s feast day with the Eucharist at the saint’s gravesite. In the 6th century, officials began separating and moving remains because the church required altars to contain the bones of martyrs. In the Middle Ages abuse and fraud became problems as some people attributed magical powers to relics and churches competed to obtain unusual items to establish a reputation and recruit church-goers. Also, greedy charlatans pawned off animal bones as remains of saints. Measures agreed upon at the Council of Trent, 1545-1563, were aimed at ending these abuses. Today the Congregation for the Causes of Saints in the Vatican handles the authentication and preservation of relics, verifying legitimacy and issuing certificates of authenticity. The church forbids the sale or trade of bodily-remains relics.