As I left Mass one Sunday in May, the first words in my pastor’s parish bulletin column got my attention: “I am ashamed of my University.”

My pastor and I share Notre Dame. Thirty-four years separate our degrees, but the gulf in our opinion about The Obama Affair, with its unprecedented media scrutiny, began in 1967. It was the year a group of progressive Catholic educators, led by Father Theodore Hesburgh, CSC, issued the so-called “Land O’Lakes Statement on the Nature of the Contemporary Catholic University,” a declaration that was destined to make the campus ground-zero in the Catholic culture wars.

An opening sentence of that document was as arresting as the beginning of my pastor’s column: “To perform its teaching and research functions effectively, the Catholic university must have true autonomy and academic freedom in the face of authority of whatever kind, lay or clerical, external to the academic community itself.”

- Related Articles

- Day of Reckoning

- The Time and the Place

- Defining Moment

It was the Declaration of Independence for American Catholic higher education, recognizing that it could not credibly enter the conversation about national goals unless it had the academic freedom enjoyed by the secular academy.

At the same time, Notre Dame and Saint Louis University were pioneering a changeover in governance from religious communities to predominantly lay boards of trustees, a move that was to become standard for the nation’s Catholic institutions of higher learning. As president of the International Federation of Catholic Universities during the years following the Land O’Lakes statement, Father Hesburgh worked to get its core ideas adopted by the Vatican.

Rome, however, was much more comfortable with Catholic universities chartered by the Vatican with a juridical relationship with the institutional church. Hesburgh was moderately successful in promoting the American model, a state-chartered institution held in public trust by an independent board of trustees, but it was, all the way into the 21st century, a two-steps-forward, one-step-back nudging of the Vatican toward an acceptance of the Lake O’Lakes statement.

Other presidents

In retrospect, it should be noted what did not happen at a Notre Dame commencement a decade after Land O’Lakes. Jimmy Carter, a born-again Christian who supported abortion rights as governor of Georgia, won the first presidential election since Roe v. Wade had legalized abortion. He was invited to speak a year later at the 1977 Notre Dame commencement. No objection was raised to Carter’s abortion position.

If a bishop had inquired, the answer would have been that Carter was being honored — along with other honorary degree recipients that year — not for his views on abortion but for his advocacy of human rights, in his case as a dimension of U.S. foreign policy. However, Republicans roundly criticized his speech as soft on Communism, and it was no accident that Catholic conservative icon William F. Buckley Jr. followed Carter on the commencement podium a year later. The fact that Buckley had earlier rejected a papal encyclical on Catholic social teaching stimulated no protest.

The next flashpoint came in 1981, when President Ronald Reagan, only a few weeks past an assassination attempt, honored a commitment to speak at the University’s commencement. In many ways, it was a mirror image of the Obama event, with the important exception that no bishops weighed in as they did on Obama. While Reagan exists in memory as a congenial conservative who suffered a debilitating disease with great grace, it was decidedly not his patina among liberals at the time. They tried to launch a national protest over the “Gipper’s” record on peace and justice issues.

After an attempt on the life of the pope the week before commencement, the Secret Service introduced new security protocols that ratcheted up the tension already surrounding a graduation featuring a president still recovering from his wounds and wearing a bullet-proof vest under his white shirt.

This time, it was the Catholic Left’s turn to challenge what Hesburgh had earlier described as the mission of a Catholic university: “Notre Dame must be a crossroads where all the vital currents of our time meet in dialogue, where the great issues of the Church and the world today are plumbed to their depths, where every sincere inquirer is welcomed and listened to . . . where differences of culture and religion and conviction can co-exist with friendship, civility, hospitality, respect and love.”

Three years later, New York Governor Mario Cuomo arrived on campus for a nationally publicized defense of Catholic politicians who said they personally opposed abortion but would not try to impose their views on a pluralistic country that thought otherwise. He was substituting for Democratic vice presidential candidate Geraldine Ferraro, whose bishop had warned her to change her pro-choice stand. Abortion was now center stage.

Criticism of Notre Dame for providing Cuomo a platform was so intense that Hesburgh wrote a widely syndicated article arguing that Catholics ought to concede that an absolute prohibition of abortion was probably not a political possibility in the United States and they should work instead to make abortion law more restrictive.

In 1992, during the presidency of Father Edward (Monk) Malloy, CSC, the commencement speaker was George H.W. Bush. There were objections to inviting an incumbent president in an election year, but the real furor was over giving pro-abortion rights Senator Daniel Moynihan the Laetare Medal as an outstanding Catholic. The committee recommending candidates for the honor relied on an analysis (by a Catholic organization) that showed his voting record in accord with Church positions about 70 percent of the time.

The seamless garment

If one agreed with Chicago Cardinal Joseph Bernardin’s “seamless garment of life,” which gave moral primacy to a consistent ethic of protecting life, including issues ranging from nuclear proliferation to welfare programs, a case could be made for the New York Democrat. However, abortion was the issue trumping all others. Notre Dame’s local ordinary, Bishop John D’Arcy, boycotted commencement, as he would do this year.

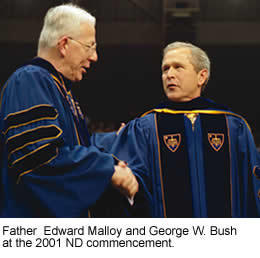

It was perhaps not coincidental that the very next year, 1993, saw the formation of the Cardinal Newman Society, a self-appointed guardian of orthodoxy in Catholic higher education. The society focused on recipients of honors at graduation ceremonies on Catholic campuses, but it did so with its own litmus test. The junior Bush, a pro-life president (who, unlike Reagan, expended political capital on the issue) was given a pass to speak at Notre Dame in 2001 despite the fact that as governor of Texas he had approved far more death row executions than any of his counterparts. The Church was against capital punishment, it was explained, but it was not an “intrinsic evil” like abortion.

In between George W. Bush and Obama, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops in 2004 issued a provisional statement on “Catholics in Political Life.” It stated, “Catholic institutions should not honor those who act in defiance of our fundamental moral principles. They should not be given awards, honors and platforms which would suggest support for their actions.” Given the document’s title, some, including Notre Dame, have taken its injunctions as referring only to Catholic politicians. It was evident by the reaction to honoring President Obama, a Protestant, that many of the nation’s bishops applied it more widely.

If one were to adopt the wider interpretation and read its implications backward, the Notre Dame commencement appearances of presidents Carter and Ford, who favored controlling but not banning abortion at the state level, would fail the abortion test. Reagan and both presidents Bush would have trouble with Church teaching against capital punishment, which would seem to meet the test of a “fundamental moral principle.” The 2004 document also casts a shadow of speciousness over the argument that the problem with Obama was the honorary degree. Even without this customary token of esteem, an invitation to address graduates can be reasonably construed as a prohibited honor if the invitee holds views contrary to Church teaching, not to mention the document’s forbidding such a person a “platform.”

The respected English Catholic publication The Tablet put the issue this way: “It is the equivalent to saying that a president, despite representing a social revolution in relations between the races, despite having a political agenda aimed at greater social justice and equality, must nevertheless be regarded as tainted by evil and shunned accordingly, because of the issue of abortion. It is not a view that would find much sympathy in most Catholic circles in Europe.”

There are two views of Church vying here. One defines the Church as at root a countercultural force, confronting an increasing secular society at every turn while steering clear of common ground it perceives as cooperating in any way with evil. The other approach is to be in a culture but not of it, engaging a pluralistic society and trying to effect change in values through argument that respects, even as it disagrees with, other opinion. Notre Dame has opted for the latter.

Lost in the heat of the Obama debate was an April international conference at Notre Dame praised in The New York Times for advancing an intellectual reform movement in the Islamic world. It was, noted the Times columnist, a scholarly meeting that “probably could not have occurred in a Muslim country.” And it was exactly what fathers Hesburgh and Jenkins meant by the “crossroads” metaphor.

My wife and I happened to be talking to Father Hesburgh in his office on a Friday last March. We were discussing how he and fellow members of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission had paved the way for Obama’s election by recommending federal voting rights legislation passed in 1964 and ’65. We had just touched on the president’s views on abortion and stem-cell research when his secretary brought in a fax. His eyes are bad, so I read it to him. It was the announcement to trustees of Obama’s acceptance.

Hesburgh said simply, “Well, if you have disagreements with someone, you may as well have him over to your place.”

It was the Land O’Lakes Statement, briefly put.

Dick Conklin retired in 2001 as associate vice president of University Relations at Notre Dame.