William Corby lay dying, stretched out on a bare wooden plank aboard a Union army steamer that was transporting sick and wounded soldiers north up the Chesapeake Bay toward Washington, D.C.

It was June 1862. The staggering human costs of the four-year Civil War were only beginning to mount, and the notoriously deliberate commanders of the Army of the Potomac were pondering how to take the Confederate capital of Richmond with the fewest losses possible. Meanwhile, heat and disease were doing death’s dreaded work in the place of Southern bullets.

Burning with fever, the young Holy Cross priest was unable to eat and spent a delirious 24 hours on the journey from White House Landing, Virginia, to a hospital run by the Sisters of Charity. Yet Father Corby was among the fortunate. As he floated toward the promise of a hospital bed and a softer pillow than the heavy blue coat folded beneath his head, hundreds of Union men were languishing in tents pitched in the swamps east of Richmond.

Disease would account for two-thirds of soldier deaths in the war. The malaria that afflicted Corby was a leading killer. The overworked Catholic chaplains of the Irish Brigade had been riding up to 40 miles a day to keep up with sick calls and funerals. Out west, one week before Corby collapsed, Father Julian Bourget, CSC, died while caring for soldiers recuperating at the Navy hospital in Mound City, Illinois. In all, three of the seven priests whom Father Edward Sorin, CSC, had released from their peacetime ministries would perish from illnesses contracted during wartime service.

Corby, an otherwise healthy 28-year-old determined to resume his post, “lay insensible” for three more days, then gathered his strength and raced back to the front, “thanks to the good medical treatment and excellent care of the ‘angels of sick and wounded soldiers’ — the Sisters,” he later wrote. His bout with malaria drew him closer to the everyday hardships of his men.

One hundred and fifty years later, the episode reveals a little more to us about the priest known mostly for his heroic absolution of the troops at Gettysburg on July 2, 1863 — an act for which Father Corby is justly remembered but to which Notre Dame’s rich and multifaceted involvement in the Civil War has unfortunately been reduced.

News of the bombardment of Fort Sumter in April 1861 — the first shots of the war — found Notre Dame in much the same spirit as the rest of the country. “The excitement has sadly interfered with the lessons of some of the hotheaded ones,” the University’s first alumnus, Father Neal Gillespie, CSC, wrote his mother.

Gillespie thought few students would leave for the fight. He was wrong. Timothy Howard enlisted in a Michigan regiment in 1862, was wounded immediately at Shiloh and soon returned to Notre Dame where he enjoyed a long career as a professor of English. He later recalled “almost every member” of Notre Dame’s student militia, the Continental Cadets, enlisting early in the war — some 40 to 50 preparatory or college students. If accurate, that number would represent nearly a fifth of the entire student body. Most fought for the North, but James Schmidt, author of Notre Dame and the Civil War, identified two Southern boys — Michael Quinlan of Virginia and Felix Zeringue of Louisiana — who took up arms for the Confederacy.

A few former students served the Union with special distinction. One was William Lynch, captain of the Continental Cadets, described as earnest and “not a little tyrannical.” Lynch recruited his own regiment, the 58th Illinois Volunteer Infantry, was taken prisoner with his men at Shiloh and was released after six months. He re-formed his unit and returned to active duty, receiving a leg wound that would dog his health until his early death as a 37-year-old brigadier general in 1876.

Another was Lieutenant Orville Chamberlain, the son of an Elkhart, Indiana, druggist, who had received an accounting degree in the spring of 1861. At Chickamauga in northwestern Georgia in September 1863, Chamberlain ran, dodged and crawled his way around a two-and-a-half-mile circuit of trenches, trees and boulders, all the while exposed to a “galling” torrent of bullets, in order to resupply his regiment with ammunition and keep them in the fight. He would eventually win the nation’s highest military award, a Medal of Honor, for his bravery.

At Notre Dame, Father Sorin sought to keep the peace, referring privately to the “wicked rebellion” but forbidding war talk among the students. Some couldn’t help themselves. When fights inevitably erupted, boys were calmed down, cleaned up and quietly dismissed. The school’s reputation for firm discipline, along with improvements like the 1863 introduction of steam heat and Notre Dame’s distance from the front, no doubt contributed to a surprising enrollment surge, most notably among students from the border states of Missouri, Kentucky and Tennessee. In the fall of 1862, General William T. Sherman enrolled a son at Notre Dame and a daughter at Saint Mary’s College; his wife, Ellen, would move the whole family from Ohio to South Bend in 1864 to wait out the war.

Staffing the paltry ranks of the army chaplaincy was not the only service Notre Dame’s president could provide. In October 1861, Sorin received two noteworthy requests. One came from Father James Dillon, CSC, asking Sorin to send his friend Father Corby to help him minister to the men of the Irish Brigade, a collection of mostly Irish American volunteer regiments from New York, Massachusetts and Pennsylvania. The other came from Indiana Governor Oliver P. Morton, who wanted a dozen sisters to train as nurses. Several volunteered as readily as Corby did. By war’s end, more than 60 Holy Cross sisters would serve in 10 military hospitals, including the first women to staff a U.S. Navy hospital ship.

Four Holy Cross chaplains, including Father Dillon, stood out for their courage under fire and their devotion to their men. Of them, Father William Corby’s service was not the longest — Father Paul Gillen, CSC, faithfully labored all four years from Bull Run to Appomattox. Nor was it the best documented. Like many soldiers, Father Peter Cooney, CSC, chronicled his tour of duty through regular letters from camp. Corby only penned his engaging Memoirs of Chaplain Life 30 years after he famously raised his hand in prayer at Gettysburg.

The son of a wealthy Detroit land broker, the young Corby worked for his father before enrolling at Notre Dame in 1853 to prepare for the seminary. When he was ordained in 1860, Sorin’s protégé was already responsible for discipline at the University and was soon named director of the Manual Labor School and pastor of a South Bend parish. But when Dillon’s letter arrived and Corby resigned these duties to board the train for Washington, it was the first time he had traveled east of Detroit. What he lacked in life experience, he would supply with character.

Respect for chaplains was a rare commodity among soldiers of the era. Few earned it. Corby, historian Lawrence F. Kohl wrote, “was certainly one of these rare men.” Having beaten malaria, he rejoined General George B. McClellan’s massive force in time for a week of hard combat in its ill-fated push toward Richmond.

Surprised by a Confederate strike during the Seven Days Battles, the Union troops pared down to essentials. The chaplains of the Irish Brigade abandoned their expensive chapel tent. Corby left behind his clothing, some books “and all the sermons I had ever written.” By week’s end, he reported, the brigade had lost 700 men, “nearly every one of them Catholics, and we may almost say none without having shortly before received the sacraments.”

The armies disengaged, and in Virginia the summer of 1862 passed mostly with camp life, marching and, for the chaplains, works of mercy. Corby celebrated Mass at every opportunity, heard confessions, attended to the sick and prayed for his men. At Harper’s Ferry he baptized an unchurched soldier condemned to death by firing squad.

The statue outside Notre Dame’s Corby Hall might as easily depict him on horseback. At the Battle of Antietam in September 1862, the Irish Brigade was ordered into the fight at a full run. Corby spurred his horse and galloped along the line, shouting for the men to make an Act of Contrition. He offered absolution and watched them go. Hundreds fell within minutes and Corby dismounted to hear the confessions of the dying men. “I shall never forget,” he wrote, “how wicked the whiz of the enemy’s bullets seemed as we advanced into that battle.”

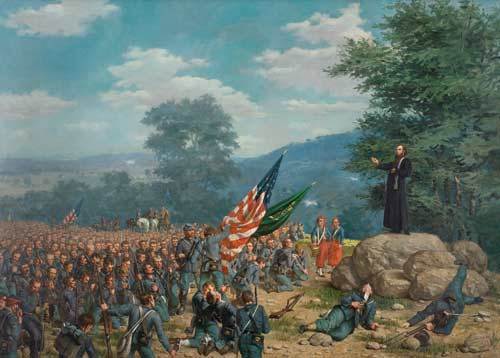

He witnessed the “slaughter pen” of Fredericksburg that December and the burning forests of Chancellorsville in spring, the months passing in blood and withering tragedy before his climactic moment at Gettysburg the following July. By the time the Irish Brigade reached the hills south of town on that battle’s second day, Corby had seen enough death to know what to do. At 4 o’clock, with Rebel cannons aiming at their lines and the orders given to “fall in” and “take arms,” Corby reminded Colonel Patrick Kelly that weeks of marching had left no time for spiritual preparations and requested a moment to pray with the men.

“The roar of the battle rose and swelled and re-echoed through the woods, making music more sublime than ever sounded through cathedral aisle,” one observer later wrote. For Corby the scene evoked the day of judgment. His eye passing over thousands of men, Catholics and non-Catholics alike, Corby explained what he was going to do, urged an Act of Contrition and fresh commitment to their duty, then raised his hand as he uttered the words of absolution. Officers removed their hats; many dropped to their knees in prayer. The attack order came and Corby turned once more to watch hundreds of men running toward the last minutes of their lives.

Young no more, Corby would see much of the Union’s final campaign before the war ended and duty called him home to what would be a succession of distinguished terms as the president of Notre Dame and of the short-lived Sacred Heart College in Watertown, Wisconsin. As historian Kohl adjudged in his introduction to the 100th anniversary edition of Corby’s Memoirs, his “splendid moment on a boulder in Gettysburg’s wheatfield was not distinctive, but representative in a life of devotion to his faith and to the people he served.”

John Nagy is an associate editor of this magazine. He recommends both James M. Schmidt’s Notre Dame and the Civil War (The History Press, 2010) and Lawrence F. Kohl’s edition of Memoirs of Chaplain Life (Fordham University Press, 1992) for your summer reading list.