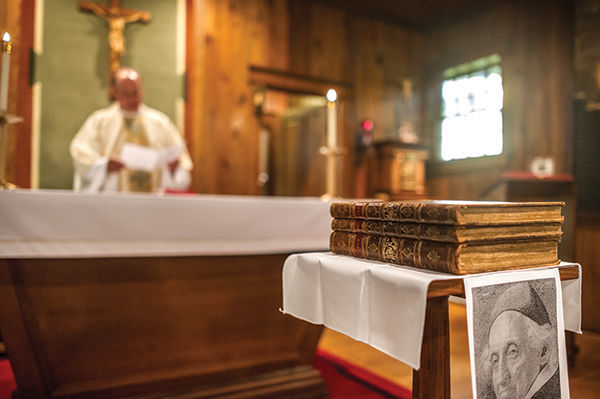

When three Sisters of Loretto processed into Notre Dame’s Log Chapel for Mass this summer, their delivery of a treasured artifact marked a moment evocative of the more than 200-year history of the Catholic Church in the United States.

The sisters were carrying a Bible bound in tooled, gold-lettered calfskin in three volumes — two for the Old Testament, one for the New. Printed in Philadelphia in 1790 by Mathew Carey, an Irish émigré who had apprenticed under Benjamin Franklin, the book was one of only 400 first-edition Catholic bibles Carey produced to serve what was then a tiny, far-flung and not especially wealthy population of American Catholics. Only a few dozen copies are accounted for today.

Among Carey’s customers was Father John Carroll, soon to be ordained — in England — as the first U.S. Catholic bishop. Carroll ordered 20 copies, each one costing about a month’s wages for a skilled artisan of that time. One copy he gave to 24-year-old Stephen Badin when Carroll ordained him in 1793 as the first man to become a Catholic priest on what was then U.S. soil.

Father Badin, a tough, assertive and prickly Frenchman who had left his native country in disgust with its revolution, almost certainly carried this weighty gift with him later that year when he set out on foot from Baltimore to Pittsburgh. There he boarded a riverboat, floated down the Ohio, disembarked at Limestone Creek and walked another 100 miles or more to the Catholic settlement in central Kentucky where he built his first cabin and began his frontier ministry.

Badin was a circuit-rider, a horseback missionary whose six-week sorties enabled him to reach the English-speaking Catholics pouring over the Appalachian Mountains, the French-speaking Catholics left behind by their empire, and Native Americans — some of whom encouraged his efforts to care for their souls even as the U.S. government forced many of them to leave the Old Northwest.

He also bought land in large quantities, like the 524 acres on the banks of pine-shaded waters in northern Indiana that later became the University of Notre Dame.

Too big to fit in saddlebags, Badin’s Bible always stayed behind in his Kentucky home. And when the middle-aged refugee returned to France for a decade starting in 1819, he left it behind for good. Soon it found its way into the hands of his neighbors, the Sisters of Loretto, who were busily turning their own rough-hewn school into an impressive, red-brick academy on Badin’s old farm. From there the holy books graced the school library’s shelves, then moved to the archives, then disappeared altogether into the vault beneath the sisters’ infirmary.

Last year, a volunteer librarian sorting through such forgotten holdings identified the three old tomes as a Carey Bible. “She looked up and said, ‘This is so rare, if you choose to let it go, you should talk to Notre Dame,’” recalls community archivist Sister Eleanor Craig, S.L.

After some research, thought and negotiation, the book’s final journey began. On the first Sunday in July, members of the Loretto Community walked it from their chapel down to Badin’s old house, pressed it to the bricks and read aloud from the Gospels.

One week later, a delegation climbed into cars that Badin could only have envied and drove to Notre Dame in time for the Log Chapel Mass at 7 p.m. celebrating the feast of the first Native American saint, Kateri Tekakwitha.

Within minutes, the leather-bound volumes were stacked in front of the altar on a tall table draped with a plain white cloth. The Bible stood just a few feet above the resting place of its former owner, who was reinterred at Notre Dame in 1904 shortly before the construction of the Log Chapel — the replica of Badin’s original log cabin — on the same site. The next day, at the Hesburgh Library, before a battery of local television cameras, Father Badin’s Carey Bible formally joined the University’s Rare Books collection, where it should prove especially useful to scholars of American religion.

Reflecting upon that reunion, Professor Kathleen Sprows Cummings, director of the Cushwa Center for the Study of American Catholicism, sees signs of a greater unity at a time when the Church could use them.

“Inscribed by a Catholic bishop, owned by a Catholic priest and a religious congregation, published by a lay leader, received on the feast of a lay woman, this Bible knits together the priestly, religious and lay vocations within the Church, all collaborating in the vineyard of the Lord,” she said after the Mass. “And surely that is something worth celebrating.”

John Nagy is an associate editor of this magazine.