A few things indicated that the world premiere for the documentary film Hesburgh might be different, but nothing had prepared director Patrick Creadon ’89 for what he witnessed that night in the theater. He never expected to hear so many sniffles and choked-back sobs.

Washington, D.C., moviegoers had filled theater 1 at the E Street Cinema during the dinner hour on Father’s Day 2018. Dozens of others had lined up outside, hoping to grab seats left empty by those who’d bought advanced tickets.

After 104 minutes, the credits rolled on the story of Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, CSC, a leader in education and civil rights and a priest who could bridge divides, resolve conflicts and create new possibilities where none had previously existed.

As she led the post-screening Q&A, veteran journalist Anne Thompson ’79 of NBC News had to stop a couple of times because she had become so emotional.

“I realized that night we had something special,” Creadon said.

Before this premiere at the American Film Institute’s documentary festival, the team behind Hesburgh thought the film might get airtime on public television, and maybe would play in a few theaters in Chicago, New York and South Bend.

Members of the Hesburgh team during production in December 2016: (l to r) Adam Lawrence (archive producer), Liz Hynes '17 (production assistant), Tanner Cipriano '17 (production assistant), Patrick Creadon '89 (director), Caroline Clark '16 (associate producer), Julia Szromba '18 (additional editor), Daniel Clark (camera operator), William Neal '14 (editor).

Members of the Hesburgh team during production in December 2016: (l to r) Adam Lawrence (archive producer), Liz Hynes '17 (production assistant), Tanner Cipriano '17 (production assistant), Patrick Creadon '89 (director), Caroline Clark '16 (associate producer), Julia Szromba '18 (additional editor), Daniel Clark (camera operator), William Neal '14 (editor).

The response in Washington that night changed things: Hesburgh will screen in Chicago on April 26 and begin a theatrical run throughout the country starting on May 3.

How exactly did a documentary film about a Catholic priest make its way to a nationwide release? That story involves the FBI, a trip to 30 Rockefeller Center, a 26-year-old who bet on himself and Creadon’s vision for a story he believes the country needs to see right now.

It all started with another film. In October 2015, Creadon needed a place to conduct interviews for a different Notre Dame-related documentary. As the Los Angeles-based director planned the shooting of what would become Catholics vs. Convicts in ESPN Films’ 30 for 30 series, he reached out to a well-connected family friend in Chicago, John Scully ’64.

Creadon asked Scully to help him secure space at the Union League Club of Chicago, where the filmmaker would end up interviewing former Fighting Irish football stars Tony Rice ’90 and Pat Terrell ’90 as well as Dave Wannstedt, the former University of Miami defensive coordinator and Chicago Bears head coach.

Scully knew people constantly pitched Creadon ideas, so when he had him on the phone, he was tactful: “Pat, I think a film on Father Hesburgh could be your next project. There’s a great story there. I know you hear that all the time, but I think you should give that some thought.”

Give it some thought? Creadon was trying to plan the second day of shooting a film that would make its TV debut 14 months later. But Scully’s suggestion stuck with him.

|

|

|

|

|

|

While making Catholics vs. Convicts, Creadon reconnected with his time as a student. The film is about the all-time classic football game between Notre Dame and Miami in 1988, but it’s also a personal trip back to Creadon’s senior year and his Notre Dame roots. His grandfather, Francis Patrick Creadon ’28, had been recruited by Knute Rockne. His father, Francis Patrick Creadon II ’60, sang in the Glee Club.

During the spring before his phone call with Scully, Creadon had stood in the pulpit of St. Mary Church in his hometown of Riverside, Illinois, to eulogize his father. It had been three months since Hesburgh had passed away, and Creadon connected the two deaths because of a story his father had told the family over and over again. “As far back as I can remember, I recall my father talking about his graduation from Notre Dame. He told us, always with great astonishment, that the president of the United States and the future pope both spoke that day.”

For Catholics vs. Convicts, Creadon interviewed his old classmate, former Notre Dame walk-on Pat Eilers ’89, in the Guglielmino Athletics Complex. When the interview ended, Eilers, now a managing director at a leading investment firm, asked Creadon what he had on the horizon.

“We’re thinking about doing a film on Father Hesburgh.”

“Done,” Eilers responded with a reassuring head nod.

Creadon tilted his head and his eyes shifted into a quizzical squint. “What’s that mean? Done?”

“Done,” Eilers repeated. “You want to make that film, I’ll raise the money.”

“I knew in that moment we would tell this story,” Creadon says.

The project met a necessary threshold for Creadon’s producing partner and wife, Christine O’Malley. “We tend to be interested in people who are ordinary people who do extraordinary things with their lives. What they’re doing has a great effect on the world,” she says.

“The projects we pursue end up being ones that both fascinate me and intimidate me,” Creadon adds. “I need to have a deep desire to explore a subject and I need the challenge that I might not be able to pull it off. Fear of failing is probably my biggest and best motivator.”

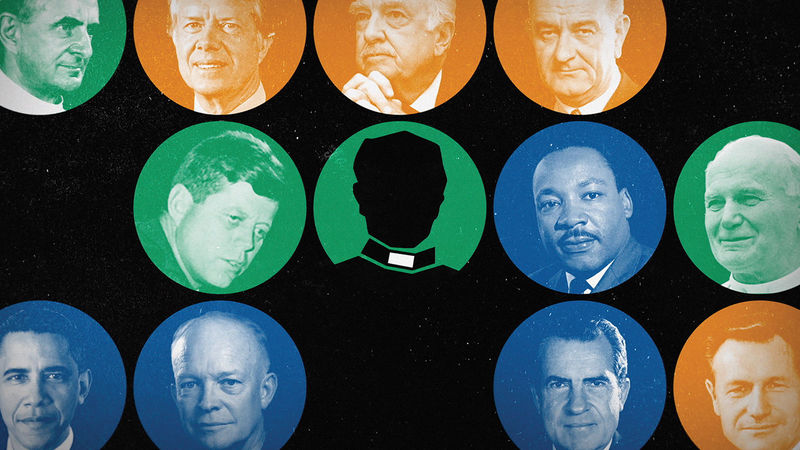

Hesburgh served the University of Notre Dame as its president for 35 years. His image graced the cover of Time magazine. He was appointed to 16 presidential commissions. He had a bestselling autobiography, God, Country, Notre Dame, that sold more than 300,000 copies before its second edition. He holds the Guinness World Record for receiving the most honorary degrees. He went Mach 3 during a ride in the SR-71 Blackbird spy plane. He lived a massive life, and his Wikipedia page shows it. It’s well over 4,000 words long.

“I wanted to make something original. The play Hamilton was a big inspiration. I wanted to make this film cool and fun. And we had to find stuff that hasn’t been reported or hadn’t been seen,” Creadon says.

To succeed, the film had to be made independently. The filmmakers did not solicit or receive any financial support from Notre Dame. Creadon and his team had complete editorial control.

Including Creadon, more than a dozen Domers worked on Hesburgh. Caroline Clark ’16 served as an associate producer, Julia Szromba ’18 provided additional editing and senior Alex Mansour composed the music. Even though most members of the team hold Notre Dame degrees, the goal was to make a film for a general audience. O’Malley didn’t go to Notre Dame (though her father, James P. O’Malley ’61, and grandfather, George O’Malley ’30, did). As the story began to take shape, she asked herself, What is the first-time viewer going to take away from this film?

“We had to have a balance in the storytelling. This had to be something for a person with no perspective on Father Ted and for someone who knew him,” she says.

The production team sifted mountains of research. They combed through books — ones Hesburgh wrote and others written about him — and more than 20 hours of never-before-released audio interviews.

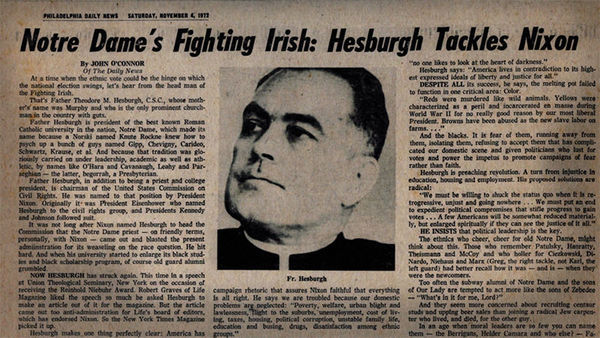

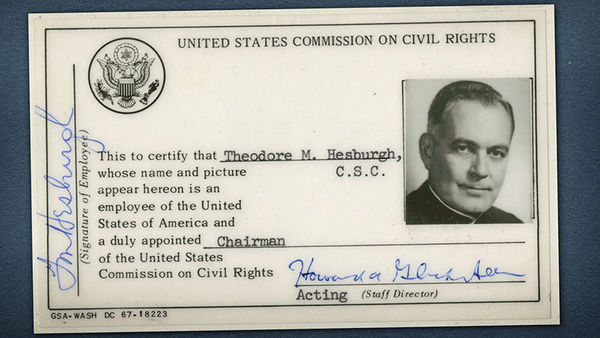

They acquired a 436-page document comprising the FBI’s Hesburgh files. It contains notes on the priest’s plans to have dinner with a Soviet ambassador and details the routine background checks required when U.S. presidents appointed him to commissions. It includes a February 1962 letter signed by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover in which Hesburgh is called a “loyal American of excellent character.”

CIA documents offered a personal touch: a formal letter with a handwritten note at the bottom informing Hesburgh they were never able to find the scarf he thought he left behind.

An audiotape records a president in the Oval Office bashing Hesburgh. Another president’s journal notes Hesburgh’s off-the-record meeting with the leader of the free world.

Archive producer Adam Lawrence camped out at the University Archives on the sixth floor of the Hesburgh Library. He spent countless hours going through stacks of letters, newspaper clippings, pictures and other artifacts the staff brought him. “They’re pushing up carts of material to my table,” he says. “To me, that’s a good time.”

Lawrence’s search took him around the country. He headed to the Chicago Public Library, the Chicago History Museum, the Vanderbilt Television News Archive and the NBCUniversal Archives. He tapped the UCLA Film & Television Archive, the Associated Press, ABC, Getty, Reuters and the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. In the Alabama state archives, he found footage of Hesburgh conducting hearings with the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. He also found segregationist politician George Wallace rallying against the commission’s work. “That was a gold mine,” he says.

He dug into the presidential libraries of John Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon. His research stretched to Vienna as he gathered material on Hesburgh’s work with the International Atomic Energy Agency.

The trip to NBCUniversal in New York was probably the strangest. At Rockefeller Center, the 37-year-old researcher unearthed news footage unseen since before he was born. A guide helped him enter a windowless room cramped by a maze of film canisters stacked in towers. There Lawrence picked out some canisters by dates and chose others blindly because their labels had faded blank. The guide then fed the film through a machine and the motion pictures lit up what had passed for a TV screen in the 1950s. By using some of the footage, O’Malley Creadon Productions became the first group to digitize these pieces of history.

The crew shot interviews on campus at Notre Dame and in Chicago, Boston, Los Angeles and Washington, D.C.; in Monterey Bay, California, and in Cheyenne, Wyoming. They ate beignets in New Orleans, conducted an interview, and then drove three hours to Mobile, Alabama, to shoot another the same day. Notable interviewees included Ted Koppel of Nightline, former Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta and former Senator Alan Simpson.

“The biggest challenge was finding the small private stories and private moments that impacted him,” says Creadon.

For those, he interviewed Hesburgh’s brother, niece, bartender, administrative assistant, caregiver and driver. “Those interviews are going to tell you more about Father Ted than Wikipedia can. We needed those to provide a full picture of who this man was.”

As all the interviews and archival research landed back in Los Angeles, an editor had to put them together. Nick Andert ’10, who edited Catholics vs. Convicts, had started on Hesburgh, but had always planned to step away before it was completed.

This left Creadon and Co. searching for the right replacement. They tried a pair of seasoned professionals who spent a few weeks with the project, cutting together a couple scenes that didn’t quite fit. This project wasn’t for them.

“The editor is the person who has to make it all work. They take a million ideas and they have to make it flow seamlessly. They’re the most important position on the filmmaking team,” Creadon explains.

Andert went to bat for William Neal ’14, an assistant editor on Catholics vs. Convicts who had worked alongside him on Hesburgh but was unproven to lead on a project of this magnitude. “William’s your guy to finish this movie,” he told the director.

Neal, then 26, spent more than a year working full-time to edit the film. He locked himself in his office stringing scenes together and finishing the voiceover narration that he and Andert had started to write. Days would go by without Creadon hearing a word.

“He’s a quiet worker. Then he’d show me a three-minute sequence and it worked. It was really good storytelling. He gets an MVP ball on our team.”

Something else happened during the making of Hesburgh. The life of this priest began to have impact on the production team. One producer started going back to daily Mass. Neal, despite being raised a devout Catholic, had stopped being a regular Sunday churchgoer — it’s not the typical thing for young people in Los Angeles. “Working on this got me going back every Sunday,” he says. And during production meetings, whenever a topic aroused disagreement, O’Malley would suggest they try “to be a little ‘Father Ted’ about this.”

Creadon thinks about Hesburgh daily. “For me personally, a subject has never rubbed off on me so profoundly.”

About the time of the film’s world premiere, Creadon taped something to the wall at his bedside, just beyond the books on his nightstand and next to the phrase, “Be a Great Dad Today”: a small, red piece of paper on which he had written “Kindness.”

“If Hesburgh had a secret weapon, it was his kindness,” Creadon says. “We’re missing that in the world today, and a little bit of kindness goes a long way.”

Creadon’s film has made its way through the festival circuit, receiving awards and building momentum for the nationwide theatrical release. At the Waimea Ocean Film Festival in Hawaii, it picked up a “Best Film” award. More than 100 people woke up early for a morning showing at the Napa Valley Film Festival, and an Indianapolis theater filled on a Tuesday afternoon during the Heartland International Film Festival. After the screening, a woman raised her hand and told Creadon, “I don’t have a question. I just want to thank you for restoring my faith in humanity.”

Hesburgh continues to receive this type of response. When the filmmakers started, they figured they had embarked on a historical project, but given the times the movie has become a timely story. That’s why Creadon wants as many people as possible to see it.

“We’ve lost our way,” he says. “We can’t speak to each other. We’d rather shout over each other. Father Ted’s story of leadership and kindness shows there is another way, and it’s something we can all live up to.”

Jerry Barca, who has produced two 30 for 30 films for ESPN, including Catholics vs. Convicts, is a producer and co-writer for Hesburgh. He is the author of Unbeatable: Notre Dame’s 1988 Championship and the Last Great College Football Season (St. Martin’s Press, 2013).