Heading off into the suburban night, I make my way to a 24-hour IHOP.

Illustrations by Brett Affrunti

Illustrations by Brett Affrunti

The place is full of kids, plus a smattering of adults with nowhere better to go. On one side of me, four high school boys dressed in red, their team’s colors, have just come from a football game. On the other side, an older couple has covered their table in napkins. I’m not sure why.

I sit in a booth by myself and wait, reading a book while people around me talk and laugh. I know soon enough that what I’m searching for isn’t here.

When the waitress finally brings my eggs and scurries off, I have to chase her down for my hash browns. I resist having coffee. Then I would never go to bed, which would leave me with even more hours to kill.

My 6-year-old goes to bed by 9, my wife by 9:30, but I’m not wired that way. I’m a night owl. During the day, our home is full of arts and crafts projects and PBS kid shows and imaginary worlds of mermaids and fairies, but all that life and activity disappears in the night. When my wife and daughter go to sleep, the house is mine alone. In the quiet, I can hear our old house creak and settle.

Night after night, I stay up late. Even when the work day has worn me out, I reach for the iPad and sink into the couch. Thirty minutes, 60 minutes, 90 minutes later, I’m still on the tablet, scrolling from one alarming article to another. I have no reason to resist sleep, no need to put off the inevitable, but still I do. My head in a fog, I stay up till the fuse is burned down. Sometimes I wish I had the nerve to take a hammer to the iPad and put myself out of my misery.

Other nights go differently. I’ll be full of energy, and a familiar restlessness will slink under my skin. I’ll need to get out.

I’ve roamed all over in the nighttime. I’ve gone to Target and walked the nearly deserted aisles, debating whether to buy deodorant, dish soap or who knows what, while workers load shelves and count the minutes till close.

Under the glow of streetlights, I’ve taken runs around the town common, passing the post office, funeral home and city hall, all of them shut and dark after the day’s business. I’ve taken late-night drives, riding on lonely roads past houses with the twinkle of a TV in the living room.

Illustrations by Brett Affrunti

Illustrations by Brett Affrunti

I’ve gone to jazz jams, blues jams and folk open mics. The music, sometimes brilliant, sometimes not, was never enough to keep me coming. I’ve sat in bars surrounded by serious drinkers who know each other, but becoming a regular would require spending a significant amount of time on a barstool, a dedication to the drinking life that I don’t need or want.

A nearby Dunkin’ Donuts is open till midnight, and I’ve sat there sipping hot chocolate, watching as nurses and snowplow drivers fuel up on caffeine and hustle off to their late shifts. The atmosphere is sterile and unremarkable. I could be in a thousand other Dunkins and they would all be the same. This particular one once had a TV, but customers argued so much over whether to turn on CNN or Fox News that the owner tore it out.

I venture everywhere alone. One night I go to a movie, and after it lets out, I walk into an almost empty parking lot and see two people just standing around and chatting. And I recognize myself. Years before, my friends and I went to the movies all the time, and sometimes we weren’t ready to go home when the film was over. So we stood outside the theater and talked about anything and everything, the parking lot emptying around us.

Now, years later, I have no movie buddies. I live in a town where I don’t know many people. My old friends are scattered about the country, and making new ones isn’t easy. I assume most people my age have mortgages and children and are more interested in decompressing at night and going to bed than wandering around the suburbs with me. I don’t blame them.

Looking at the two friends talking in the parking lot, I think of old times before hopping in my car and driving away.

My restlessness keeps me moving. It always has been with me, this need to meander and explore. I assumed the onslaught of grown-up responsibilities would have cured me of it, that I would feel at peace with my job, home and family, with the stability that comes with adulthood. Still, I grow antsy. If I’m home for too many nights in a row, I can feel the walls narrow.

Why? Why can’t I be at rest? Is it a longing to connect with others? A need to distract myself from the thoughts rattling around my head? The biggest reason, I suspect, is that I’m trying to break out of the never-ending routine. That routine of life, of waking and working, of eating and sleeping, is comforting in its predictability. It’s also constraining. Often, as many of us do, I yearn for more.

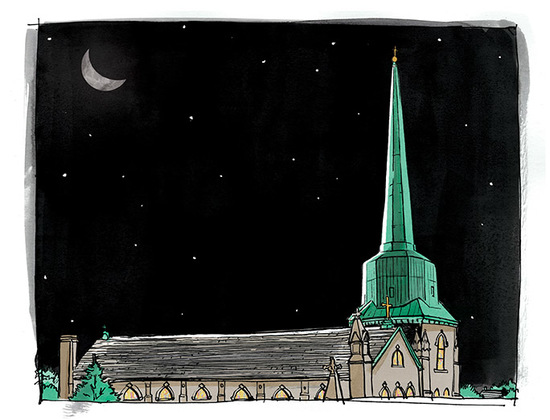

The place I return to most is the adoration chapel at St. Patrick’s. It’s located down the street from our house, next to the fire station, where a piece of twisted metal from the World Trade Center is displayed as part of a 9/11 memorial.

Sitting in the rectory basement, the chapel is small, with maybe three dozen chairs. Plastic rosaries hang from every seat. On the altar rests the tabernacle with the Eucharist, a solitary candle burning next to it. To one side hangs a crucifix, to the other a picture of Mary and Baby Jesus. Otherwise, the walls are unadorned. Nothing to distract from the Eucharist.

The chapel is open all night. I usually stop by at 10 or 11 p.m., and a few faithful souls are always in the seats. The parishioners try to make sure someone is adoring the Eucharist at all times. At the door is a schedule where people sign up for hour-long “adorer” shifts. If they can’t make it one night, they search for others to substitute.

I take a seat in the back row. Many in the chapel know each other. Regulars in the faith, they wave to one another as they come and go. Staring at the Eucharist, they say the rosary or flip through the weathered Bibles and prayer books kept at each seat. They also peek at their phones. The adorers may be devout, but they aren’t monks. The pervasiveness of technology can’t be avoided, even here.

The chapel is quiet, so quiet you feel self-conscious if you cough. The sounds of people turning pages and shifting in their seats amplify in the silence. Some of the adorers whisper their prayers, but in the softness, you can hear their mutterings, like you’re eavesdropping on their private thoughts.

The sound of cars rolling by on Route 135 drifts in through the window. During the morning rush the road teems with traffic, but at this hour cars are sporadic. When a late-night train pulls into a nearby station, the chapel fills with the rumble of the train’s diesel engine.

The adoration chapel is a funny place for me to end up, considering the Church stopped being a regular part of my life a long time ago. As a kid, I attended Mass devoutly every Sunday, but I lost that sense of obligation in college. I grew and learned and questioned, and the Church no longer felt like an essential part of who I was.

But no one exits Catholicism completely. It may be the ultimate “Hotel California”: You can check out anytime you like / But you can never leave. My family and I live within a stone’s throw of St. Patrick’s. We are part of the rhythm of the church, even if we don’t enter its doors. We know the Mass schedule because our street fills with churchgoers’ cars. Out our windows, we see the steeple. We’ve watched brides and grooms pose for pictures and heard bagpipers play for funerals. The bells, which chime on the hour, keep time in our lives. If I’m reading to my daughter and they chime 9 p.m., I know to wrap up the story and get her to sleep.

Walking into the adoration chapel, I don’t feel out of place. This is a world I know. I grew up in it and, despite my best efforts, have not gotten away from it. Sitting in the chapel feels familiar, like returning to an old haunt. Its stillness reminds me of when I was a kid, when my family and I would visit churches on the night of Holy Thursday. The churches were quiet and dim, and you could almost picture the struggle and betrayal in a garden a long time ago.

Before leaving the house at night, I talk to my wife. “I’m going out,” I tell her.

“Where are you going?” she asks.

“The chapel.”

She chuckles. She’s amused by my need to go off into the night. I suppose other husbands would be content to ease out their waking hours by drinking beer and flipping on a meaningless game, but my wife understands that’s not me.

Shuffling off to bed, she’ll stare at her phone and the latest outrages on Twitter for a bit before calling it a day. Unlike me, she doesn’t feel the need to fight and wrestle with sleep. If she’s tired, she goes to bed. Simple as that. She welcomes the respite of pillow, blankets and slumber.

In her bedroom, our daughter sleeps surrounded by stuffed animals. I’m amazed by how quickly she falls asleep. She has no restlessness, no worries to keep her awake. Bless her.

As I stand outside the chapel, our town is sleepy and still. A man walking his dog may pass by, and the lawn sprinklers by the fire station may come to life, hissing and rotating, but the night is otherwise hushed and calm. You would never know that, behind the nondescript door, adorers are awake, alert and full of purpose.

Sitting in my usual spot, I watch them. One woman prays with her palms open to the ceiling, while another stares at Mary and Jesus, her gaze unflinching. Another woman sits on the floor in front of the altar, as if she needs to be as close to the Eucharist as possible.

I wonder what personal concerns compel them to come here at such hours. A book sits near the door where people write their intentions. One person wrote, “Thank you for this sweet world,” while another hoped a family in need would find a “safe home with a yard.” One adorer wrote simply, “For Nana and Papa.”

I don’t pray when I’m at the chapel. As with going to church, praying is not a regular part of my life anymore. But when I sit in the quiet, I think and reflect. I like the sense of mystery there. It’s not something you can easily summon if you don’t go to church. You can’t order an egg, cheese and sausage sandwich at Dunkin’ Donuts and expect to be confronted by the great questions of our universe. At the chapel, I’m reminded that I don’t have all the answers, that much that makes up our existence is unknowable.

My favorite part of the Mass as a child was the sign of peace. Shaking hands, wishing “peace be with you,” I was forced to reach out, to make a connection with others, something I can’t seem to find in my late-night wanderings at IHOP and the local bar.

One night at the chapel, a man in gym shorts hustles to a seat. Checking the time, he breaks the silence. “The 10 o’clock Liturgy of the Hours will begin on page 1010,” he says. He looks about the room, curious who might join him in prayer. Turning around, he looks right at me. I don’t meet his eye.

Only four people are in the chapel. The man hurls himself into prayer, his voice deep and strong. One other man follows his lead. They recite from a section of the prayer book called Night Prayer. The readings include passages from Psalms, Revelation and the Gospel of Luke. “You shall not fear the terror of the night,” reads the verse from Psalm 91.

Here at the chapel, I fear not the night, for I am not alone. There are no new drinking buddies here, no friends to hang out with in the parking lot, but these people of faith provide good company. My nights are long and restless, but at the chapel, I am at ease and my mind is clear, surrounded by people of good hearts and warm intentions.

“May the all-powerful Lord grant us a restful night,” the adorers recite as the prayer concludes. The chapel once again returned to silence, I embrace that promise.

A resident of Natick, Massachusetts, John Crawford is senior editor of Babson Magazine, the alumni publication of Babson College. His Twitter handle is @crawfordwriter.