One does not speak directly to the king of the world. A public audience with the monarch of the Mossi people in West Africa, the Mogho Naba — literally “head of the world” — involves standards of decorum that include addressing him through intermediaries.

It stands to reason that one also does not toss a soccer ball at the Mogho Naba’s head in the playful manner one might exhibit toward a schoolchild. But the German nonprofit Spirit of Football, an organization interested in education and international goodwill led by founder and president Andrew Aris ’00, has its own rituals.

Every four years the group carries a special soccer ball, in the fashion of the Olympic torch, from the game’s modern birthplace at Battersea Park in London around the globe toward the site of the World Cup. This spring they visited 15 countries in Europe and the Middle East over three months en route to Russia. In 2010, the journey to the tournament in South Africa included a visit to the city of Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso and a meeting with the Mogho Naba.

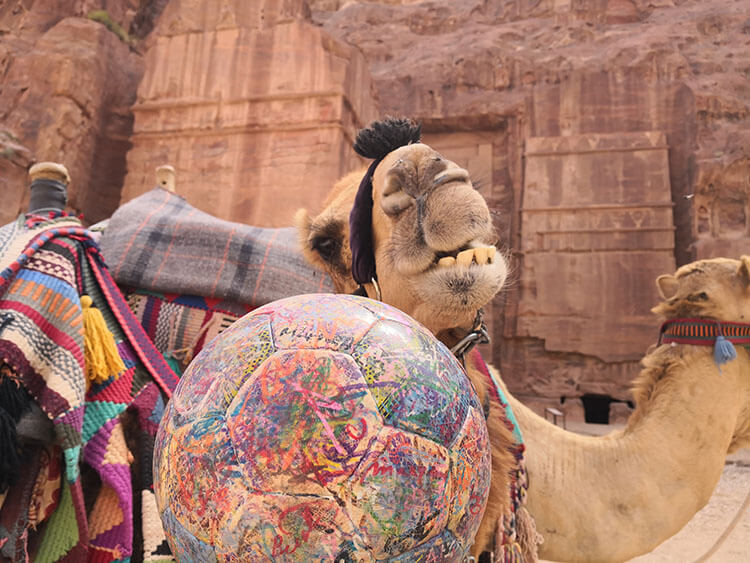

At each stop, whether from heads of state, religious leaders, international soccer stars, students, Special Olympics athletes or Middle Eastern refugees, they collect signatures on the ball. Over time it becomes a marker-smudged patchwork of names blurring together to represent soccer’s unifying force. “One ball, one world,” goes their hopeful refrain.

Photos courtesy of Spirit of Football

Photos courtesy of Spirit of Football

So, how about it, Mogho Naba?

Phil Wake, a musician, magician and Spirit of Football co-founder from England, held the ball and explained the autograph procedure to the king in Burkina Faso’s official French.

“We would love to have you sign the ball, but we have just one rule: everyone who signs it has to do a header first.” And up went the ball in an arc toward the throne.

“Everyone in the room was like, ‘Protocol broken! What’s going on here?’” Aris says.

The Mogho Naba did not follow the rule. Instead of heading the ball back, he caught it.

Aris recalls that Wake, “the cheeky devil,” immediately pulled a yellow card from his back pocket — regal status accorded no special treatment. When Wake tells the story, the card is not merely a warning yellow, but a disqualifying red. Aris chuckles with skepticism about that: “I don’t think he showed the king a red card.”

Whatever sanction he received, the Mogho Naba did not accept it.

“No, no, no,” he said, standing up. “I’m the goalkeeper. I’ve played football my whole life and I find your rule unfair because goalkeepers are allowed to use their hands.”

As quick to reconsider on the basis of that argument as he was to deploy the card in the first place, Wake withdrew the penalty and instituted an addendum in the Mogho Naba’s name: Everyone who signs the ball must perform a header except for goalkeepers, who may catch it.

The account of meeting the Mogho Naba is part of Spirit of Football’s repertoire for school presentations, not only because of the fairytale images of a retinue of attendants and majestic fang-baring lion statues at the king’s side, but for the moral of the story about rigidity and flexibility within the rules, about communication and compromise. And, most crucial to the organization’s mission, about the sport’s power to remind people from different worlds that we all inhabit the same one.

One ball, one world.

Scenes from YouTube videos of Spirit of Football’s journeys to the World Cup put flesh and bone on that sentiment. Games among players bundled up on snowy tundra or barefoot on hot dirt share the same enthusiastic pitch, oceans and continents apart. One punted ball floats through a Notre Dame Stadium goalpost, and a boisterous crowd bounces another off the head of a Nelson Mandela statue in Johannesburg. The president of Honduras and a wheelchair-bound Special Olympian head balls against backdrops of dignified statecraft and raucous celebration. Uniformed soldiers in Colombia and Chile play along with the rule of header first, then signature. A cop and a costumed Spiderman in Times Square, too.

All of which sounds like the kind of carnival Aris’ old friends would have expected him to be pied-piping around the world someday — serious in mission, but mischievous in spirit.

“He’s just a beautiful human being,” says his former roommate Adam Sargent ’99, now associate director of academic services for Notre Dame athletes. “It’s easy, when you first get to know him, to see that there’s depth to Andrew, great depth. He’s a very caring person, but there’s a levity, too. He embraces the absurd, even seeks it out. He has fun with it.”

In college, Sargent says, the New Zealand native (pictured at center above) gave off a “no worries” vibe. Aris remains the same free spirit today, a leader of the global educational initiatives his organization sponsors, but also the flailing arms that conduct the playground whooping wherever he goes.

The essence of it, for Aris: “I think that within each of us, there’s a little kid.”

Soccer’s cultural connective tissue has been the leitmotif of Aris’ life. In New Zealand as a boy, with a father from Scotland and mother from England, he grew up feeling isolated while playing the world’s game “with a bit of a chip on my shoulder” in a nation that was apathetic about it. People could even be hostile, questioning his manhood for preferring “the beautiful game” to the country’s beloved rugby scrums.

His motivation never wavered, and he played on New Zealand’s under-17 and under-20 national teams. New Zealand’s coach in the mid-1990s? Bobby Clark, the former professional goalkeeper from Scotland who would go on to coach for 17 years at Notre Dame. Then a friend of the Aris family in Auckland, Clark suggested that Andrew play college soccer in the United States.

Aris ended up at Notre Dame, becoming a key player as a forward from 1996 to 1999 under Clark’s predecessor, Mike Berticelli. From South Bend, Aris went on to play for the Rot-Weiss professional club in Erfurt, Germany.

“My whole life was really based around traveling and football and feeling that the game was this sort of international passport for me,” Aris says, “because wherever I went, I met people, connected with them, played football with them.”

Studying for his master’s degree at the Erfurt School of Public Policy, he conceived of a way to extend that connection beyond his playing days. Theoretical questions about how soccer could promote education, economic growth and social cohesion became the practical focus of Spirit of Football.

With a few partners, Aris opened the doors in 2005 with the objective of creating international goodwill around the World Cup that Germany would host the following year. Since then, from their Erfurt offices, they have taken their ideas — and, in World Cup years, the ball — around the world.

The focus is education, not competition, with the game as a means to teach children values that transcend sports — fair play, collaboration, empathy and acceptance. Everybody plays regardless of ability when Spirit of Football visits a school. Students must exhibit mutual respect. When a goal is scored, even the opposing team joins in the celebration.

After the games, groups develop skits, perform song and dance routines or create artwork based on the principles they’ve learned. The curriculum adapts to the needs of the schools or communities they’re visiting, but at the heart of it is a belief in active learning, and in participation and cooperation as the most effective ways to open minds to our common humanity.

Global upheaval has tested that idea — and Spirit of Football’s vision of “an educational institution that could also become a hub of the community” in its own hometown. In 2015, when hundreds of thousands of refugees from the Middle East began fleeing to Germany, the organization’s board convened via Skype to consider its response to the burgeoning humanitarian crisis.

“When we travel with the ball, people have opened their hearts to us,” Aris says, recalling that conversation. “We have an obligation to help people that are fleeing from war or other circumstances . . . to give them the feeling that other people care about them and really to help them get a foot in a new community.”

How they helped demonstrates Spirit of Football’s broad and adaptive approach. Bearing balls and goals and bibs, they started pickup games at refugee emergency centers.

“Before we knew it,” Aris says, “we had made friends.”

Weekly community events with food, music and movies, art projects and games for the kids strengthened the bonds. Practical support included assistance for refugees in learning German, navigating bureaucracy, finding jobs. Students from the university where Spirit of Football conducts a seminar volunteered ideas and time.

A dark shadow hovered over those everyday needs: the reality of what the refugees had fled. For some it was the murder, imprisonment or torture of family members, for all the destruction of life as they knew it. Guiding the suffering toward psychological help became a priority.

In the years since, many refugees have established themselves in Germany, owing an assist to Spirit of Football. Then, as the 2018 World Cup approached, the ball’s path from England to Russia offered an opportunity for these new members of the Erfurt community to be Spirit of Football representatives in their native region.

“That was our dream,” Aris says. “To have those guys carry the ball, carry the torch.”

Not all their stories have a happy ending. Denied visas to enter Turkey, Lebanon or Jordan, the refugees could not make the trip, but the official Spirit of Football contingent did — with corporate funding for the first time. They also lengthened each stop to deepen their impact in those scarred communities, replacing the “in-and-out” whirlwind of previous workshop tours.

At the Azraq refugee camp in Jordan, which shelters tens of thousands of people, the organization didn’t need much time to accomplish what some there considered impossible. First they were told the training must be limited to men, but Spirit of Football insisted on gender balance. That was granted, with a stipulation requiring separate demonstrations for men and women because they would refuse to participate together.

“Within a matter of days we had men and women playing football together,” Aris says. “It’s possible.”

On a return visit, Azraq residents presented Aris with a banner they made to represent what Spirit of Football means to them. It’s a communal work, expressing their collective idea of the game, experienced through the organization’s outreach as a source of love and peace, “a vision of how they want their world to be,” Aris says, his voice catching a little at the memory.

Traveling to Russia and the World Cup, Aris also had occasion to speak with the imam of Istanbul’s famous Blue Mosque. At a time of division and of disappointment in institutions expected to promote peace and stability, the imam said, people hunger for other symbols of unity.

“The ball,” Aris says, “is a beautiful symbol for bringing people together.”

Jason Kelly is an associate editor of this magazine.