Every Sunday morning, I read “By the Book” in The New York Times Book Review. The interviewee often is asked which guests they would invite to dinner. The combination might be as disparate as Michelangelo, Jane Austen, Nelson Mandela and Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Life spans rarely connect. So I decided to have a dinner party for four minims (French for “little ones”) from different decades of the 87 years of their existence at Notre Dame. My dinner would comprise one each from the 1840s, the 1860s, the 1890s and the 1920s. The Notre Dame boarding school took in minim boys ages 5 through 12 from 1842 through 1929, though occasionally a 3- or 4-year-old and even more 13-year-olds slipped through that net.

My first guest, from the 1840s, would be a descendant of the French-Canadian fur trappers who settled in the northern Indiana area. The French language would have attracted Father Edward Sorin to them as he explained his plan of turning a cluster of makeshift buildings surrounding a log cabin chapel a few miles north of South Bend into a school. There, elementary school-aged children in a school-deprived Indiana could learn. Outsiders liked the idea, too. Quickly some took the lake route: Chicago to St. Joseph, Michigan, then again on the St. Joseph River to South Bend. This outer world of Illinois (which Sorin called the “granary” for Notre Dame) heard about the school that taught grammar, reading, mathematics, music, science and more. The Catholic religion was supposed to be gleaned by just being there. All religions were welcomed.

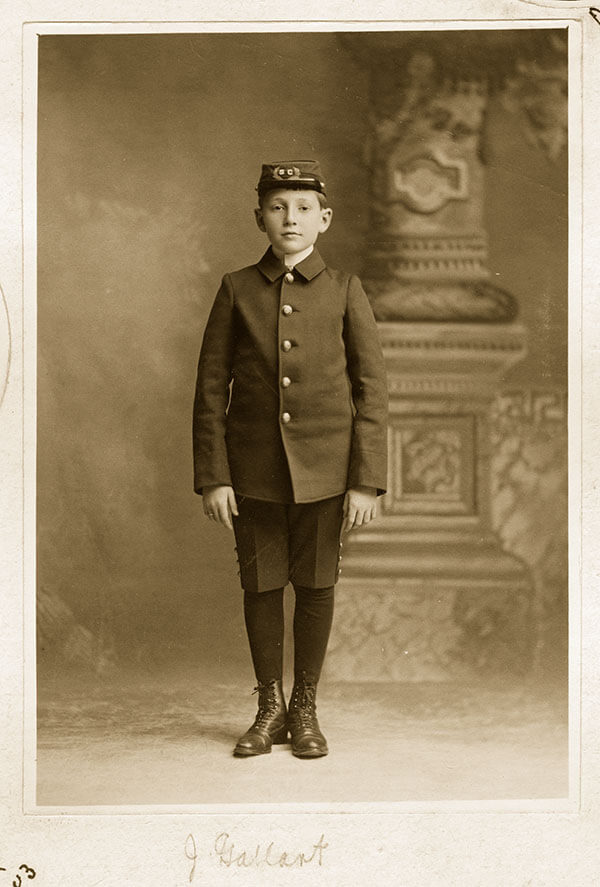

José Porfirio Gallart, courtesy University of Notre Dame Archives

José Porfirio Gallart, courtesy University of Notre Dame Archives

In 1844, with the stroke of a pen, the State of Indiana declared Notre Dame to be a university. Word spread. Upwardly mobile parents impressed by this auspicious title started sending sons by foot, by a water route, or by wagon. Since small boys were bona fide students of the University, they were charged the same rate as the upper division young men. An enormous cost. Despite that, some parents tendered more. Mrs. Conill from Iowa offered Father Sorin more cash if it would go toward her child’s access for tutors or advanced placement but not toward “puddings and pies.” (“Don’t tell him I wrote,” she added.) Education meant that much.

My second dinner guest, this one from the turbulent 1860s, would probably be a Southern boy from the Confederacy or a border state. Because of the hostilities, he might be escorting his sister destined for the newly relocated Saint Mary’s Academy. “We won’t send the boys until you take their sisters as well,” Sorin had been told, so he was delighted with the parallel school.

Because the Sisters of the Holy Cross taught the girls so effectively at Saint Mary’s, Sorin invited them in the early 1860s to run his boys’ school at Notre Dame. Sister M. Aloysius Macaire, CSC, ran the school for decades exactly as Sorin wanted. A minim from Tennessee, later Denver’s Judge Ben Lindsey, who became an advocate of the country’s juvenile justice system, would recall his time as a minim. In a letter to the University president, Father John Cavanaugh, CSC, Lindsey said of Sister Aloysius, “how much thousands of men like myself owe to her, no one . . . can estimate.”

The Notre Dame and Saint Mary campuses in the Civil War consisted mostly of Union supporters, but about 9 percent came from the Confederacy. Sorin clamped down on discussions. No snowball fights; no arguments. Some eruptions occurred between the Northern and Southern girls at Saint Mary’s, so the same rule was enforced. Union General William Tecumseh Sherman had young son Willy at Notre Dame and older daughter Minnie at Saint Mary’s. Maybe Willy, a Notre Dame minim, might come to my reunion.

The third guest, this one from the 1890s, would be from Cuba. An influx of Cuban students had enrolled, thanks to the recruitment energy of Brother Paul the Hermit McIntyre, CSC, dispatched from President Andrew Morrissey’s office. Quite taken with the coffee, he stayed as long as he could. Strong backing from Indiana and Michigan businessmen with connections in Cuba also promoted the value of a Notre Dame education. The school catalog with photos was printed in Spanish in the 1890s. Would I be lucky enough to entertain José Porfirio Gallart from Guantanamo? He came as a minim in the 1890s, finished his B.S. in chemical engineering at Notre Dame and then earned a doctorate in England in music. He became one of Cuba’s most famous composers.

- God, Country, Notre Dame et cetera

- 175 and Counting

- En Route

- The Passing of Ancestral Lands

- The Stationmaster

- The Littlest Domers

- The original home-grown do-it-yourself meal plan

- Gettysburg, 1863

- Washington Hall

- Commencements through history

- Cartier Athletic Field

- The old ND&W

- As ND as football, Mother’s Day and community service

- Notre Dame vs. Army: The rivalry that shaped college football

- Bound volumes, illicit lit

- Mock political conventions

- The Collegiate Jazz Festival

- When the Irish got their fight back

- The damnedest experience we ever had

- 40291

- It takes a University Village

The fourth minim, this one from the 1920s, might have traveled to Notre Dame from a distant city by streamliner to Chicago’s Union Station. Trains had eliminated the previously formidable barriers, smoothing the way for students from both coasts. He was as crazed about sports as others in the Roaring ’20s. He lived in St. Edward’s Hall, the Sorin-designed edifice built as a palace to house the “princes” forever. In 1929, this fourth guest at my dinner might be Leonard A. Hauf, eighth grade valedictorian who was lucky enough to graduate. Could he recall a bit of his speech as the last diplomas were conferred in 1929? Would he tell what it was like to be the last minim out, the one who closed the door? Was he one of the ones who promised their friends he would return four years later as a freshman?

During my imaginary dinner, the four minims’ spirited conversation showed me that a blue and gold thread joined them all. They laughed at the same memories. The first hoot erupted at mention of the inflexible rising hour of 6:30 a.m., actually an improvement over the 5:30 recorded in earlier years. One minim explained that in the earliest days grammar was taught by Brothers with French accents followed later by Brothers with thick Irish accents. Civilization was saved when the Sisters of the Holy Cross took over and explained everything in perfect English. The minims remembered “Caj” (Cajetan Gallagher, CSC), the brother who was their friend, tutor, lifeguard, provider of first aid and assistant with their weekly letters home. Professor John Zahm, CSC, was a favorite guest lecturer, capable of making theology and evolution fascinating. He, like Paul the Hermit, had gone on recruiting trips, his to Mexico. The four remembered when the honor roll was published and their names appeared along with degree students, thus convincing them that they belonged. They remembered marching in matching uniforms in step right behind the older cadets. And the games! The cheering! The biggest fans known to the sports heroes of Notre Dame were the smallest ones on campus, and my guests remembered well the statistics on players and the odds for victory. They also had their own meets in swimming, racing, handball, “base ball” and certainly in the newfangled game of football, at first played with innings. Music! It was almost expected that they played an instrument in the band or the orchestra. Three of the four were contemporaries of Father Edward Sorin, who lived on the campus to the end of his days and played marbles with them. He even sent a velocipede from France.

The boys’ congenial recollections made me believe that 1929 was too soon for this world to end, but by the mid-1920s the value of the presence of the “toddlers” (a critic’s term) on campus was questioned. Desiring a reputation as a national research university and considering the noisy playground at St. Ed’s a distraction, the administration under President Charles L. O’Donnell, CSC, decided to terminate the program as the decade closed. He himself presided at the graduation, giving out 20 diplomas to the eighth grade class as the entire school participated with skits and music. Washington Hall rang out with “Hike, Notre Dame” and “The Victory March” as the minim orchestra played for the last time.

The minims were the ones who had contributed Yankee dollars, Confederate certificates and gold from Cuba and Mexico, as well as in-kind merchandise to keep the University afloat. Without this influx of tuition money or one-tenth of a farmer’s field or even, on occasion, cases of Kentucky bourbon, would Notre Dame ever have reached this point where minims were no longer necessary? Students from such illustrious families as Sherman, Studebaker, Coquillard, Rockne, O’Neill and Lindsey were now memories.

As my fitting farewell to the four minim alumni bound by that blue and gold thread, for the last course of my dinner I would serve apple pie, because no food is mentioned more in the students’ Scholastic magazine than apples. Apples were there in all forms: directly from an Indiana orchard; eaten singly; in pies and tarts; as applesauce, apple juice or cider. To a victorious team went a whole bushel. After an academic achievement an apple was bestowed. Father Sorin would bring apples to St. Ed’s Hall as the best treat possible. One student who got permission to take a walk around St. Joseph Lake revealed what he really did. He confessed in the November 23, 1867, issue of Scholastic that he “went to a farmhouse for cider and apples — bully for me!” Later that month, the same student continued in his journal: “a letter from pa — too full of morals.”

Did I mention that these minims had a streak of independence in them?

Marion T. Casey is collegiate professor of history at the University of Maryland's University College, teaching online students studying abroad. Contact her with minim stories at caseyemery@aol.com.