Summer arrived late to New York City, but when it finally got here it proved as intense and unapologetic as the people it came to afflict. I stood in a circle of fragrant strangers, pressing sweat from my hairline, discussing war and shareholders’ equity, two subjects I know virtually nothing about. It was a rooftop party in the Nolita neighborhood. The sky was full of smog and glass and cornflower light. The odor of traffic.

“So — you just finished an MFA at NYU, right?” one of them asked.

“Yes,” I said. “In May.”

“Creative writing!” she smiled. “That sounds fun! I’m jealous. So what’s next for you?”

I suddenly couldn’t recall how or why I had appeared on this roof, in a wrinkled sundress from high school, with a Solo cup of tap water and a bad headache. These people were equipped with practical degrees, retirement funds, mental health, engagement rings. Accustomed to the company of fellow aspiring writers — all doubt and debt and insomnia — I found myself bashful among the gainfully employed, observing their 10-year plans and sensible circadian rhythms the way I had observed the taxidermy at the American Museum of Natural History earlier that day: with admiration and a little sad fear.

“I mean long-term,” she clarified.

“So in other words,” grinned a young man in a very white shirt, “what do you want to be when you grow up?”

As a child, I secretly believed I was a mystic.

I don’t know when my attempt at mysticism ended or began, but ages 7 through 10 seem especially strange to me now. I recall hearing a story about a young woman who locked herself in a room without any food, sunlight or water. She did nothing but pray. I was instructed to imagine unimaginable happiness, because that’s what she felt when God finally spoke to her.

The adult who told me this story had surely not intended it as a career suggestion, but the pursuit appealed to me, and I figured I had a pretty good shot at success. When it came to contacting the divine, I possessed a confidence that I have tried and failed to lasso since; I believe it was a strain of confidence unique to childhood, one that can only thrive in a body too light to trigger an airbag.

The evidence that I used to reinforce my eligibility was tangential at best, and I feel a special blend of shame and amusement to recall it now. My qualifications included an aversion to fireworks, an intolerance for violent movies and the ability to smell oranges being peeled many rooms away. When I shut the door to my bedroom, perched my parakeet on my cat’s head and released my rabbit from her cage, a peaceful, unlikely coexistence ensued, for which I credited my (mystical) orchestration.

I recorded the evidence of these prerequisites in a notebook, certain that God would understand their relevance even if I didn’t. It was a time when everything was charged with overwhelming significance, everything reached outside of itself, and I was bad at coping. I held onto my potential mysticism in the hope that it might redeem my oversensitivity, my anxiety, my strangeness. If those three qualities weren’t helping me achieve unimaginable happiness, then they were merely obstructing the imaginable kind.

On a cold evening this past spring, I sat across from a writer at a restaurant in Brooklyn. “I will never be content,” he announced, sipping his wine and neglecting his fries. He addressed a clock on the wall behind me.

Anointed The Next Big Thing at a young age, his career is radiant with awards, critical declarations of brilliance, seven-figure book deals, film rights, celebrity circles, global attention — all the trappings of literary fame. He had been a mentor of sorts over the prevoius two years, and I arranged a meeting because it was the final stretch of my master’s and I wanted him to answer a question that had set up camp in my brain months prior: What’s the point of all this, anyway?

“Sure, I’ve written a few books,” he continued. “But I’ve never done anything that befits an only life.”

Under the table, my cuticle began to bleed. He transferred his gaze from the clock to my face as though surprised to see me there. “Sorry — what did you want to talk about?”

Back in South Bend, Indiana, the rituals I developed as a child to train for mysticism were as bizarre as my supposed eligibility. Sometimes I prayed until I fell asleep — the only ritual that fit the part and not the one I favored. More urgently, it felt necessary to master shuffling a deck of cards. I kept a tattered set on my shelf and practiced over and over in the dark, experimentally dedicating the effort to God. I once saw a teenage boy in a café who had cancer; I was 8 and he was beautiful and I felt very cold on the ride home. Every time I lost an eyelash after that, I would wish for him to survive. Because he didn’t have any, and I had a surplus, and even adults agreed that lost eyelashes were sort of supernatural, the equation seemed sound. Sometimes I would lie in bed and tug at my lashes, trying to free a few on his behalf.

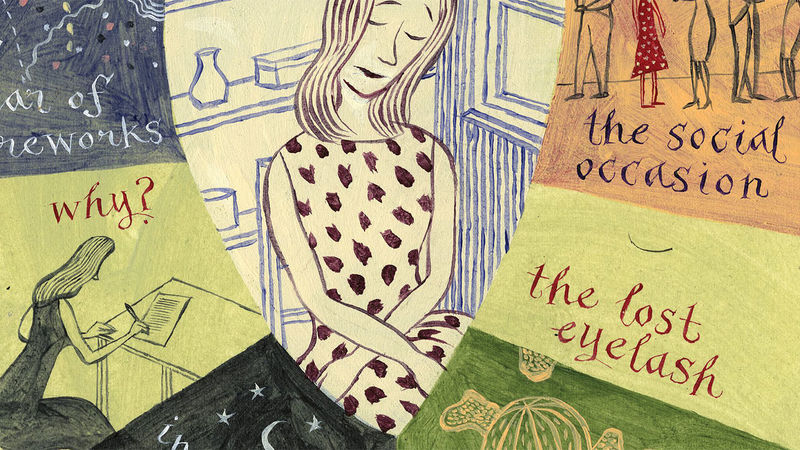

Illustrations by Jeffrey Fisher

Illustrations by Jeffrey Fisher

Occasionally I would forgo my sandwich at school, nebulously associating hunger and discomfort with self-denial, self-denial with God, God with — what? Unimaginable happiness, I suppose.

The secrecy of my endeavor seemed essential, and I guarded it the same way I clenched my eyes shut after bedtime when I lost a tooth, certain that if I glimpsed the Tooth Fairy she would stop appearing. The fear of killing something wondrous by looking it directly in the eye has trailed me into the pseudo-adulthood I’ve come to occupy.

I resemble a mystic even less now than I did during my peculiar pursuit of the vocation. I wear perfume, order champagne, fall in love. Things like throw pillows matter to me. I keep an Instagram account, and if there is one realm that’s decisively antithetical to mysticism, it’s social media.

Now 24 years old, I’ve been thinking about my childhood attempt at mysticism a lot lately — not only because writers spend a gluttonous amount of time analyzing their childhoods, but also because I suspect there are instructive parallels between writing and mysticism, the yearning I felt as a 9-year-old and the yearning I feel now.

Mystics and writers generally agree that close attention, the willful participation in the suffering of others, and the translation of solitude into communion are required of those who seek fulfillment. Writers and mystics spend most of their time alone in a room, trying to milk meaning from the mundane, searching for an antidote to loneliness.

When 9-year-old me appears in my mind, I recognize her at once. She knew a few things I’ve since forgotten.

In an attempt to pacify some familiar unrest, I recently consulted an anthology of writings by the French philosopher, activist and mystic Simone Weil. I was particularly eager to reread the essay “Attention and Will,” which I first encountered in a Notre Dame theology course. The essay portrays radical attention as the remedy for human fault, and it argues that “attention, taken to its highest degree, is the same thing as prayer. It presupposes faith and love.” When I first read the piece, I was 20 years old, and I hastily deemed it the thesis statement of my life. Weil argues, “The poet produces the beautiful by fixing his attention on something real. It is the same with the act of love. To know that this man who is hungry and thirsty really exists as much as I do — that is enough, the rest follows of itself.”

For Weil, pure attention is only achievable once the self gets out of the way. “Attention alone — that attention which is so full that the ‘I’ disappears — is required of me,” she writes.

I am less certain now than I was when I entered my master’s program what prose and poetry are for, but when 9-year-old me appears in my mind, I recognize her at once. She knew a few things I’ve since forgotten.

I spent my MFA years drafting five novels and one prose-poetry collection, finishing none, scrapping most. I typically read, edited and despaired during the day, then wrote from dinner until dawn, stopping when screenlight surrendered to daylight and language no longer made sense. I slept too little or too much, ate too little or too much, always at the wrong times. Courted every project with infatuation until the pages began to read as humiliating, repulsive, irredeemably bad. My shift from devotion to nausea was sudden and inevitable and not at all unique. It usually happened around page 100; I possessed neither the confidence nor the stamina to write through it. I trusted no praise and amplified every criticism, flummoxed when, months after a workshop, I picked up a professor’s copy of a submission I had since abandoned to find that half of his comments were positive, and his last note read, Do not give up on this. In my memory, he had advised the opposite.

In February, a pair of mice made a 10-day hotel of my bedroom. They were Brooklyn mice and therefore nearly immortal. At night I would listen to them merrily squeak as they chewed my walls; they were always so busy. Jealous of their work ethic and the clarity with which they went about their business, I did not sleep at all.

Even when everything was going well, my default psychological setting was apocalyptic. I spent a bewildering amount of time crying on trains, in elevators, in scarves, insensibly, and if not in silence, then with music, often Icelandic. What do you want to be when you grow up? my friends and I would ask each other like it was our favorite joke. We ransacked novels, poetry, essays, our teachers and each other for the answer.

In an essay she penned when she was just two years older than I am now, Joan Didion states that to lack self-respect is to be incapable of both love and indifference:

“If we do not respect ourselves, we are on the one hand forced to despise those who have so few resources as to consort with us, so little perception as to remain blind to our fatal weaknesses. On the other hand, we are peculiarly in thrall to everyone we see, curiously determined to live out — since our self-image is untenable — their false notions of us.”

Didion’s idea of self-respect and Weil’s idea of attention constitute the crucial difference between the 20-something who threw away five novels because she felt too much, and the child who sought union with the divine for precisely the same reason.

I have met writers who are beloved and successful, cheerless and cruel. I have stood in beautiful houses waded in the periphery of a sparkly literary scene, replete with bright victories and miserable victors who will “never be content.” Enchantment collapsed into disillusion. Clichés revealed themselves to be true: Material success often varies inversely with happiness. Sleep medicine and ragged cuticles and excuses to leave the party early accumulated.

Put simply, I don’t know what to call the desire that filled me all those years ago, but I know that it was indispensable, and I know it’s the same one that fills me now. Everything is still charged with overwhelming significance, and I am still bad at coping. Still determined to generate meaning from the mundane, still in search of an antidote to loneliness. I face a blank screen, deep in my imagination, desperate to prove the significance of life in general and my life in particular.

Despite the similarities, though, there are some differences. However misguided she was, my childhood-self understood that happiness has nothing to do with book deals and everything to do with paying attention — to the world and, crucially, to other people. Real people.

I don’t know what’s next for me, and I’m not a mystic, never was, but I want very badly to believe that orange peels, playing cards and lost eyelashes mean something. I am trying to develop enough self-respect to disappear the I. When I grow up, I want to be someone who pays attention.

Tess Gunty's creative writing has been read on NPR, and a short story is forthcoming in The Iowa Review. She is currently a New York University Graduate Research Institute fellow in Paris, where she is working on a manuscript.