On July 31, 1835, Father Stephen Badin, the first priest ordained in the United States, transfers his claim to 524 acres of land at Sainte-Marie-des-Lacs, which he had intended for the creation of an orphan asylum, to the bishop of Vincennes, Indiana. Seven years later the bishop turns over the property to a 28-year-old missionary priest from France, Father Edward Frederick Sorin of the Congregation of Holy Cross, to build a school.

On November 26, 1842, or maybe November 27, Father Sorin and his Holy Cross brothers — grateful for a meal of hot soup and bread at the home of fur trapper Alexis Coquillard after an 11-days’ journey through “Siberian” cold — brush aside offers of a bed and ask to be led to their new mission field.

- God, Country, Notre Dame et cetera

- 175 and Counting

- En Route

- The Passing of Ancestral Lands

- The Stationmaster

- The Littlest Domers

- The original home-grown do-it-yourself meal plan

- Gettysburg, 1863

- Washington Hall

- Commencements through history

- Cartier Athletic Field

- The old ND&W

- As ND as football, Mother’s Day and community service

- Notre Dame vs. Army: The rivalry that shaped college football

- Bound volumes, illicit lit

- Mock political conventions

- The Collegiate Jazz Festival

- When the Irish got their fight back

- The damnedest experience we ever had

- 40291

- It takes a University Village

After spending a frigid winter exposed to the elements and trying to rebuild Badin’s dilapidated cabin-chapel, Sorin and his brothers finish patching the roof on March 19, 1843.

In July 1843 four sisters — Mary of the Sacred Heart, Mary of Bethlehem, Mary of Calvary and Mary of Nazareth — arrive in the company of two priests, a brother and a seminarian, having completed a trip from France every bit as harrowing as Sorin’s. They devote themselves to cooking, washing, mending, nursing and care of the animals, all for the good of the school.

An architect and two laborers arrive on August 24, 1843, to start work on what would become Old College and would survive as the only original landmark from Notre Dame’s founding years.

Sorin announces in the South Bend Free Press on December 2, 1843, his intention to create a college at Notre Dame. At the outset it was “little more than a tidy French boarding school.” Rise at 5:30, Mass at 6:30, then breakfast. Periods of study, reading and recitation throughout the day, punctuated by meals, play and an evening “spiritual conference.” Candles out sharply at 9 o’clock.

Through the intercession of South Bend’s state Senator John DeFrees and the action of the Indiana Legislature, Notre Dame becomes a university on January 15, 1844. The school has about 25 students. Sorin hosts his first weekly faculty meeting.

After several failed previous motions, Father Sorin finally accepts — on May 24, 1847 — the Council of Professors’ request to expel one Willie Ord, an older student who had gone drinking and skinny-dipping in the river and, on a separate occasion, punched his drawing professor — but only concedes the point this time because Ord’s family had finally paid his tuition.

In June 1849, the University issues its first baccalaureate degrees — “Bachelor of Arts and Letters,” to be precise — to Neal Gillespie, a 16-year-old from Ohio who had studied at Notre Dame for four years and had taken the “Latin Course,” and Richard Shortis, a seminarian. Both men would become Holy Cross priests and serve terms as vice presidents of the University.

In the 1850s, per their faculty contracts, professors are required to live on the college grounds, be in bed by 9, participate fully in the religious life of the school, and to abstain from drinking under any circumstances and going into South Bend without permission.

Desperate for money, Sorin organizes in March 1850 the ill-fated St. Joseph’s Company of four Holy Cross brothers and three laymen to go west and stake a claim in the California Gold Rush. They find no gold but pay the ultimate price when Brother Placidus dies en route without a priest to administer his last rites and burial.

On January 6, 1851, with a little help from Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky and some other friends, the University secures a commission for a Notre Dame post office, Edw. Sorin, postmaster.

Father Francis Cointet dies September 19, 1854, in the infirmary amid a nationwide cholera outbreak. “The glory, the light, the joy and the life of the community,” in Sorin’s words, was the 20th person buried on campus that year as a result of the disease; more students were sent home in coffins as administrators tried to downplay the numbers lest the University be closed for good.

Alarmed by another cholera death and suspecting that stagnant marsh water at the edge of Saint Mary’s Lake might be the source of the scourge, Sorin loses patience with the neighbor whose dam prevents the creek from draining into the St. Joseph River. So when the neighbor leaves town April 5, 1855, Sorin sends half a dozen workmen with hatchets and crowbars to tear out the dam. Later Sorin purchases the property, which becomes Saint Mary’s College.

Brickmaking, an important if not super-lucrative source of income for the Holy Cross order and the school from the 1840s through the 1880s, produces about half a million “Notre Dame bricks” per year, which are sold to builders all over the Midwest.

Father William Corby, CSC, chaplain of the Union’s famed Irish Brigade, blesses the soldiers as they enter the fighting on the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg, July 2, 1863.

The Annual Catalog for 1864-65 reminds students that they must wash their feet at 4 p.m. each Saturday in winter. They may skip this routine in summer, when instead they all bathe together twice weekly in St. Joseph Lake.

In June 1865, two months after the Confederate surrender at Appomattox, General William Tecumseh Sherman speaks at Notre Dame’s 21st commencement, urging the graduates to “perform bravely the battle of life.”

In 1866, college prep student Adrian Anson, age 14, of Marshalltown, Iowa, makes his first start for the Juanita baseball club as postwar baseball fever sweeps the school. By the 1880s, students field as many as 15 teams each year; an 1894 campus map shows five baseball diamonds to one football field. “Cap” Anson is the best product of this dustcloud of ball-crazy boys, destined for the 1939 class of inductees into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

The Scholastic Year, in its September 7, 1867, inaugural issue, reports that a student from Milwaukee has returned to school in the company of a “magnificent live bald eagle,” for which his friends helped him build a 10-foot-cage. The bird would escape by November.

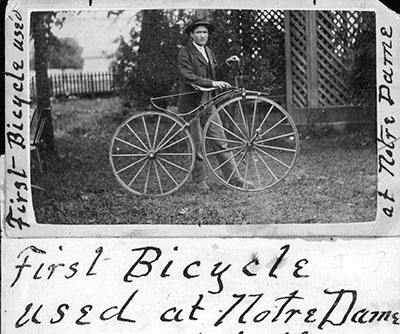

On December 10, 1868, Father Sorin sends home from Paris a velocipede, “one of the largest and best” bicycles yet made in the City of Lights.

The Law School opens in February 1869, becoming the nation’s first Catholic law school.

On May 31, 1871, Archbishop J.B. Purcell of Cincinnati and five of his hierarchical colleagues answer the age-old question, “How many U.S. bishops does it take to bless the cornerstone of Sacred Heart Church on the campus of Notre Dame?”

In 1871, Notre Dame permits students to go home for the holidays for the first time. Demand from those Chicago bound is so great that the Lake Shore Railway arranges for a special train to convey them (Notre Dame’s own “Polar Express,” you might say). Father Sorin rides with them as far as La Porte.

On June 7, 1872, the faculty and students express their gratitude toward the president, Father Corby, presenting him with a four-seater Studebaker carriage. During the fanfare and applause, the startled horses take off across the flower beds.

In 1873, Notre Dame becomes the first Catholic college in the U.S. to found a school of engineering. That same year Father Sorin, having visited the grotto in Lourdes, France, where Saint Bernadette Soubirous had seen an apparition of the Virgin Mary 15 years earlier, decides campus should have a replica of it. The Notre Dame Grotto is completed 23 years later.

Father Auguste Lemonnier, CSC, University president, suggests the creation of a Circulating Library in the Main Building in 1873. The library opens each day at 3:45 p.m., costs one dollar for a semester subscription and boasts nearly 3,000 volumes within its first three years.

On May 8, 1876, Edwin Booth, brother of Lincoln’s assassin and reportedly the best Prince Hamlet of the century, visits campus in the afternoon and performs his most famous role at a South Bend theater that night.

Officials at Notre Dame and the Western Union Telegraph Company offices in South Bend celebrate the connection of campus and city via telephone wires. On the April 6, 1878, program is a performance of the Senior Orchestra with violin, cornet, guitar and flute solos appreciated by a “large audience, chiefly ladies” listening on the other end of the line.

Student Harry Kitz, rushing triumphantly out of the flaming Main Building with his arms full of books, is smashed to the ground by what he thinks in a moment of fateful imagination is a collapsing wall but is in fact a mattress tossed out from the fourth floor. By day’s end, April 23, 1879, much of the campus in ashes, Father Corby decides students must go home but promises they will return in September to a new and improved Notre Dame.

On April 27, 1879, four days after the “Great Fire” that all but consumed the six-story Main Building and neighboring structures, Father Sorin, perched on the altar steps inside Sacred Heart Church, informs the campus community, “If it were ALL gone, I should not give up!” The core of the “new” Main Building that stands today is ready in time to welcome students the following September.

The Notre Dame Scholastic reports August 14, 1880, that the statue of Mary, weighing 4,400 pounds and “destined for the dome,” is sitting on top of the front porch of the Main Building, “has been gilded and looks really beautiful.” It would remain there until 1882.

On June 22, 1882, Notre Dame confers six bachelor’s degrees — and 40 diplomas to students completing the commercial course. Entertainment during Commencement Week features a performance of Oedipus Tyrannus entirely in Greek, rescued by the public debut of electric light inside Washington Hall.

On June 23, 1883, American historian John Gilmary Shea receives the first Laetare Medal, conceived during an informal faculty conversation on the front porch of the Main Building as an American version of the papal Golden Rose. The idea was to encourage “faith, morals, education and good citizenship” among American Catholic laypeople, despite the objections of some present that “whatever backwardness the laity had shown in the matter was mainly attributable to their own indifference or lack of invigorating zeal.”

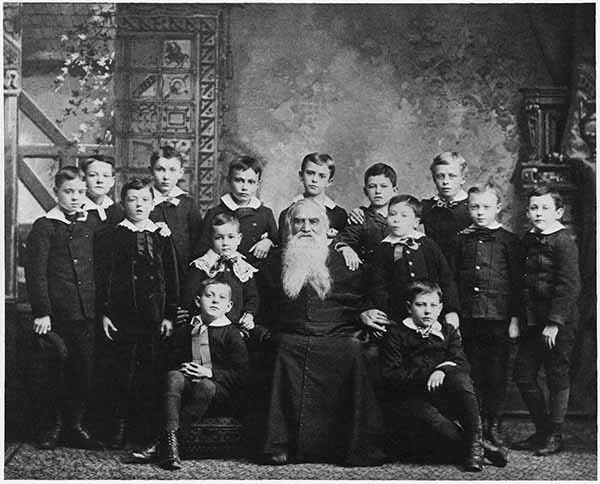

Father Sorin hosts a royal Parisian dinner November 24, 1883, and writes a play to celebrate the arrival of Edward Sorin Ewing of Lancaster, Ohio, the 100th minim — the term for pupils under the age of 12 — to take up residence in the new St. Edward’s Hall. Sorin calls the minims his “princes” and St. Ed’s their “palace.”

On March 29, 1884, having spent much of the previous three years in the American Southwest on a geological expedition, Father John A. Zahm, CSC, takes advantage of the recent completion of the Mexico Central Railway to organize the first train to travel from Mexico City to Chicago. Aboard are 10 Mexican students en route to their studies at Notre Dame.

The University announces on January 9, 1886, plans to wire all campus buildings for “Edison’s incandescent light” to replace gas lighting “in all the parlors, study-halls, class and lecture-rooms, as well as in the private rooms of professors and students.”

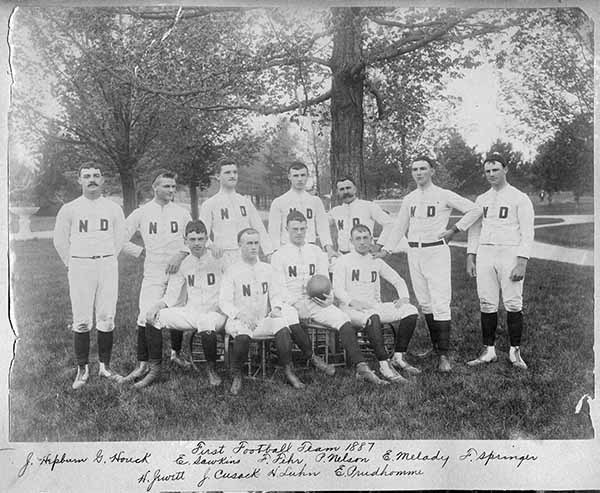

Independent and coachless, Notre Dame plays its first intercollegiate game of football, November 23, 1887, an 8-0 loss to a team from Ann Arbor, Michigan. The “champions of the West” regard the game as a warm-up to their Thanksgiving contest the next day in Chicago, and seem to consider Notre Dame mission country in football-religious terms.

Father Sorin receives a cablegram from Rome on February 20, 1888, affirming his purchase of an expensive altar attributed to the Baroque master sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini, but which is far likelier the product of one of Bernini’s students. Sacred Heart Church, finally complete, is consecrated the following August.

In May 1888, Albert Zahm, professor of mechanical engineering, cuts himself loose from a steel beam jutting out from the Science Building, now known as LaFortune Student Center, and sails to the ground in his handmade glider, an early experiment in flight that draws international attention to the campus.

The Notre Dame Scholastic announces the January 1889 opening of Sorin Hall for top college students, the first Catholic college dormitory in the United States with private rooms “large enough to encourage study and at the same time small enough to discourage visiting.”

Maurice Francis Egan, a Notre Dame professor of English, suggests in the February 1890 Catholic World that Catholic colleges should loosen outdated residential requirements to become genuine colleges instead of prep schools. But he also noted, “The rules of order and cleanliness are not more stringent or more scrupulously enforced at West Point than in Sorin Hall.” After listing the rules designed to maintain that order, he explains, “A college ought to stand in loco parentis. If it seeks to divest itself of all responsibility, it fulfills the lesser part of its mission.”

The new statue of the Sacred Heart in the “University park” (later known as God Quad), reported to be a “perfect copy” of the original in Montmartre in Paris, is consecrated June 18, 1893, to kick off Commencement Week.

Diagnosed with “Bright’s disease” or inflammation of the kidneys, and having suffered much of the year with hemorrhages and fatigue, Father Sorin, age 79, dies October 31, 1893, in his room in the Presbytery behind Sacred Heart Church.

Yeoman Third Class John Henry “Shilly” Shillington, captain of the 1897 basketball team, is one of 266 sailors killed February 15, 1898, when the USS Maine explodes and sinks in Havana Harbor, propelling the United States into a short war with Spain. A shell from the Maine honoring Shillington made several public but discreet appearances on campus before finding a “permanent” home near the ROTC’s Pasquerilla Center.

Reporters watch bug-eyed as Professor Jerome Green on April 20, 1899, shoots a message to Saint Mary’s College, confirming the Notre Dame electrical engineer as the first person to successfully transmit a message via wireless radio. Green calls the surprising media coverage “a great advertisement for Notre Dame.”

On January 17, 1903, The Notre Dame Scholastic extols the progressive triumph of the new two-story bakery and its modern mixers and dividers, capable of cranking out 300 buns a minute. The soft, doughy “Notre Dame bun” would become a staple of dining-hall breakfasts — and campus food fights — for decades.

Charming, brilliant, absentminded as a pig-tailed macaque, William Butler Yeats pays Notre Dame a visit in January 1904 and delivers a series of three lectures on Irish literature, poetry and theater. Having bid goodbye to Father John Cavanaugh, CSC, on Sunday morning, Yeats’ car returns moments later. Yeats steps out of the car and explains to the inquiring priest, “Upon my soul, Father, I’ve forgot my teeth.”

Law professor Frank E. Hering, a former ND football, basketball and baseball coach, delivers a speech February 7, 1904, in Indianapolis that is later credited for the idea of Mother’s Day.

Secretary of War William Howard Taft, future president of the United States and Supreme Court chief justice, lectures October 5, 1904, on “The Church and Our Government in the Philippines,” kicking off a lecture series that would culminate with the eminent novelist Henry James offering his thoughts on the French author Honoré de Balzac.

In April 1905, workmen finish construction of a front porch on Sorin Hall, where students couldn’t help but douse visitors with water as they came and went. It was all fun and games until they soaked the Law School dean, “Colonel” William Hoynes, Sorin’s professor-in-residence. Plans for a porch roof took shape immediately.

Carriages line up at the gymnasium to deliver dates to the seniors’ elegant Easter Ball, April 24, 1905. Complete with bunting, electric-light displays of the monogram and “’05” at either end of the ballroom and the music of Professor Charles Petersen’s student orchestra, it is reportedly the first class dance held at Notre Dame.

In 1906 two students living on the first floor of Sorin Hall, Michael and John Shea, write “The Notre Dame Victory March.”

Young poet and seminarian Charles O’Donnell, future president of the University, is selected in 1906 as editor-in-chief of the inaugural Dome, which sells 1,500 copies and turns a handsome $500 profit.

On May 3, 1906, draped in American and papal flags, a $25,000 statue of Father Sorin is unveiled at the entrance of the grounds. At 4 p.m., Father Badin’s remains, moved from Cincinnati, are re-interred in the replica of his original “Indian Chapel,” recently completed by a broadax-wielding ex-slave and foreman from Kentucky named William Arnett.

After decades of Notre Dame recruiting south of the U.S. border, an estimated 10 percent of its 1907 student body is from Latin America, mainly Cuba and Mexico.

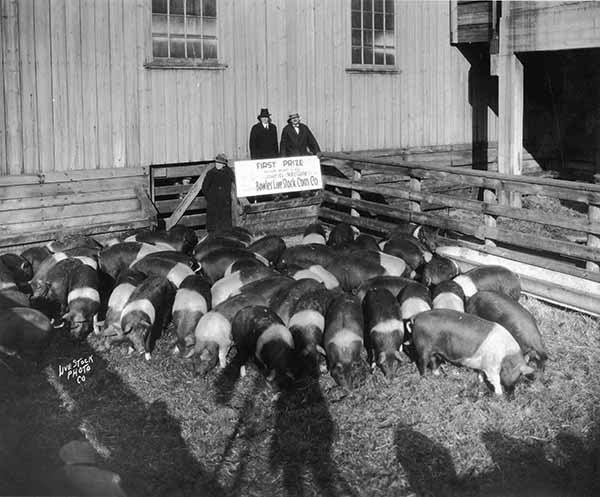

Brother Leo Donovan, who ran the University farms from 1900 to ’40, wins first prize for the best grain-fed cattle in the Hereford class at the 1912 International Stock Show in Chicago. Exhibiting beef, hogs and horses at state fairs and stock shows for 35 years, the agricultural innovator supplies and slaughters most of the beef and pork used in the University kitchens.

In September 1913, the University discontinues its policy of offering “hoboes” food and shelter each winter in “Rockefeller Hall,” a building that formed a quad with the old Fieldhouse and what’s now LaFortune Student Center, and which was otherwise a large outhouse.

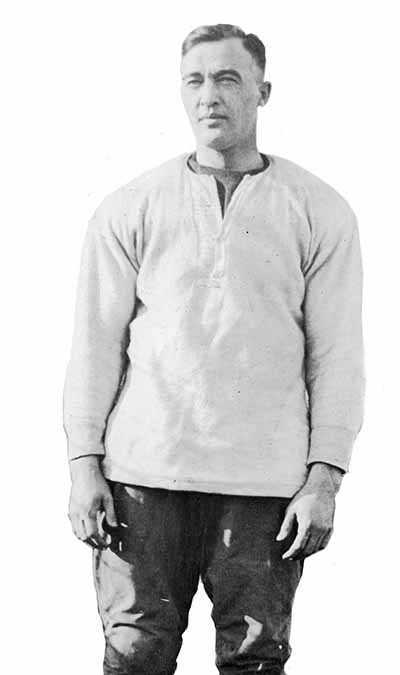

On November 1, 1913, Gus Dorais and Knute Rockne deploy the newfangled “forward pass” en route to a 35-13 upset over Army, a permanent, prominent place in the nation’s sports pages and the first profitable season in the history of Notre Dame athletics.

Making one of many appearances as a female character on the Washington Hall stage, Knute Rockne turns heads as the long-braided Pearly in What’s Next on April 13, 1914. Years later, Father John Cavanaugh remembers Rockne’s “vigorous and industrious” if not “virtuoso” performances as a flautist in the orchestra pit.

In February 1916, indignant at the poor quality of the Hill Street trolley and their rough treatment by company employees as it carried students back to campus from South Bend, students stop the ride near Cedar Grove Cemetery and begin to dismantle it, only to be dispersed by University president Father John W. Cavanaugh, CSC, while he makes his own return from town. That evening the students return and set the trolley on fire.

On April 21, 1917, two weeks after Congress declares war on the German Empire, Notre Dame students mobilize, sending 600 cadets, a Red Cross corps, a military band and a squad of chaplains to march in a patriotic parade in South Bend. Students leaving school for military training camps before the year’s end are encouraged to leave their forwarding address with the business manager of The Dome so they might have their yearbooks mailed to them.

On June 11, 1917, Sister Mary Frances Jerome, CSC, and Sister Mary Lucretia, CSC, become the first women to earn Notre Dame degrees — master’s degrees in Greek literature and chemistry, respectively.

In autumn 1917, envisioning itself as a Catholic land-grant university, the University opens a Department of Agriculture mostly on the strength of its 1,600-acre “General Farm,” eventually awarding bachelor’s degrees in seven agricultural areas before shutting its doors in 1932.

In September 1917, Notre Dame becomes the first U.S. university to offer a four-year course in foreign commerce. The College of Commerce launches in 1921 with Father John O’Hara, CSC, as its first dean.

In 1918 Notre Dame launches its Summer School to help teachers — most of them sisters in religious orders — “to make their work more interesting and more effective.” It is the University’s first foray into serious graduate study.

The Notre Dame Scholastic readers learn that athletic director Jesse Harper, coach of ND’s perennially successful baseball, basketball and football teams, is leaving sports June 1, 1918, to return to ranching in Kansas. “His vacancy will be the hardest of all the missing stars to fill in the future teams,” the magazine frets. But that track coach, Rockne? He looks pretty good.

Selected in September 1918 by the U.S. government as one of 400 universities to facilitate the Students’ Army Training Corps, Notre Dame is more an armed camp than a college campus. The War Department underwrites the $120 tuition plus $30-per-month subsistence pay for each student-soldier.

During his 19-month speaking and fundraising tour of the United States on behalf of the yet-unrecognized Irish Republic and its army, Éamon de Valera stops at Notre Dame October 15, 1919, lays a wreath at the statue of Father Corby, plants a tree and speaks of Ireland’s cause to an ardent overflow crowd at Washington Hall. He later says, “It was the happiest day since coming to America.”

The Notre Dame Scholastic reports in November 1919 that the University has reorganized itself. Under the new president, Father James A. Burns, CSC, Notre Dame is divided into four distinct colleges of Arts & Letters, Science, Engineering and Law, with each college to be further subdivided into departments. Within months, Burns begins shutting down the prep school.

By 1920 Notre Dame boasts 1,200 students, 67 faculty members, 28 buildings and a tuition of $170 per year. Some 377 of those students — more than 30 percent of the student body — are enrolled in the commerce course.

George Gipp dies December 14, 1920, after a short illness, two weeks after being selected as Notre Dame’s first All-American. His ghost has reputedly frequented Washington Hall in the years since.

The Religious Bulletin, a one-page mimeographed collection of prayers, poems, news, quotes and priestly advice, is first slipped under the residence hall door of every student in 1921. The daily communique, started by Father John O’Hara, CSC, then prefect of religion and later University president, was distributed for the next 46 years.

In 1921 Father James A. Burns, CSC, University president, raises $750,000 to secure the first foundation grants Notre Dame ever received — $250,000 and $75,000 from the Rockefeller and Carnegie foundations, respectively. Together the $1.075 million establishes the school’s endowment, today valued at more than $10 billion.

Having taken up weightlifting as a Holy Cross priest, gymnasium director Father B.H.B. Lange is named the world’s fourth strongest man in the 1920s. His gym attracts generations of bodybuilders.

Father Charles Miltner, CSC, dean of the College of Arts and Letters, announces in January 1924 curriculum changes that eliminate the three to four years of Latin and two to three of Greek that were previously required for a bachelor’s degree.

About 2,000 students, local residents and undergrads from Catholic colleges in Chicago clash with 35,000 Ku Klux Klan members at a Klan rally in downtown South Bend, May 17, 1924.

Former army chaplain and University president Father Matthew Walsh, CSC, celebrates an outdoor Memorial Day Mass on May 26, 1924, to dedicate a new door to Sacred Heart’s east transept honoring Notre Dame students who had lost their lives in the Great War. The archway is inscribed, “Our Gallant Dead//God, Country, Notre Dame//In Glory Everlasting.”

Ground is broken in summer 1924 for the foundation of “Old Students Hall,” later Howard Hall, the first of three residence halls proposed in response to the rapid growth of the undergraduate student body and Notre Dame’s increasingly ambitious outlook as a modern research university.

On October 18, 1924, watching another Notre Dame upset of West Point, this one led by the team’s historic backfield, New York sportswriter Grantland Rice sits down to write his lede: “Outlined against a blue-gray October sky, the Four Horsemen rode again.”

Father Julius A. Nieuwland’s offhand remark during a presentation to the American Chemical Society’s 1925 Organic Chemistry Symposium attracts the attention of DuPont chemists, who hire the Holy Cross priest as a consultant and develop his discovery into what eventually becomes neoprene, a signature substitute for natural rubber.

Uncomfortable with the number of students living in the city — and despite the addition of Howard, the construction of Morrissey and the bidding out of Lyons Hall — the administration in summer 1925 temporarily freezes enrollment at 2,500 students.

Conceding defeat to various pejorative nicknames assigned to Notre Dame’s football teams based on the presumed ethnicity of the school’s student athletes, New York Post and New York Daily News sportswriter Frank Wallace, class of 1923, consistently writes his stories about the “Fighting Irish” in the fall of 1925. Within two years, University president Father Matthew Walsh, CSC, has given the moniker his formal blessing.

In a rite so private that not even his family is said to have known about it, Knute Kenneth Rockne is baptized in the Log Chapel November 20, 1925, by one of his former baseball players, Father Vincent Mooney, CSC. The next day he surprises his son, Knute Jr., a minim, by receiving his First Communion with him at the same Mass in the chapel of St. Edward’s Hall.

In June 1929 the minims go home for good. One faction in the administration argues to maintain Sorin’s “princes” via an experimental school, but the allure of converting St. Ed’s into an undergraduate residence hall proves too powerful.

The Notre Dame Alumnus reports in September 1929 that excavation for the new football stadium is complete and sales of the six-seat boxes along each sideline — the primary underwriting mechanism for the construction — are going quite swimmingly. Buyers are entitled to the boxes for 10 years and receive other privileges, including preference on away-game tickets and a bronze plaque marking their box with their name.

Two months after the Stock Market Crash of 1929, University President Charles O’Donnell, CSC, lays bare Notre Dame’s financial situation to the alumni, revealing the school’s dependence on “football money” to remain in operation and arguing for the endowment. He includes an “eloquent” table listing Notre Dame’s endowment ($1 million) vis-à-vis the endowments, ranging from $18 million to $82 million, of the Ivies, Chicago, MIT and Stanford. “Aspirational peers,” he might have called them.

G.K. Chesterton visits Notre Dame in the fall of 1930, lectures in Washington Hall on Victorian literature and politics, drinks beer with students in a Sorin Hall loft and writes “The Arena,” a 54-line mini-epic about Fighting Irish football and the new Notre Dame Stadium, dedicated October 11, 1930, during a game against Navy.

Knute Rockne and seven others die when their plane goes down in a field a few miles from Bazaar, Kansas, March 31, 1931. The crash spurs reforms in aircraft design and airline safety practices.

University band director Joseph Casasanta’s arrangement of Father Charles O’Donnell’s “Notre Dame, Our Mother,” debuts October 7, 1931, at the premiere of Universal Pictures’ The Spirit of Notre Dame. It is soon adopted as the alma mater and sung during halftime of the last home game of the 1931 football season to honor the late Coach Rockne.

On February 12, 1932, a crowd nearly 2,000 strong turns out for “The Scholastic’s Boxing Show,” a tournament organized to raise money for a favorite student charity, Holy Cross’ Bengal Missions. In the hands of Dominick Napolitano, class of 1932, the bouts become an annual tradition of clean, fair fighting in the name of a good cause.

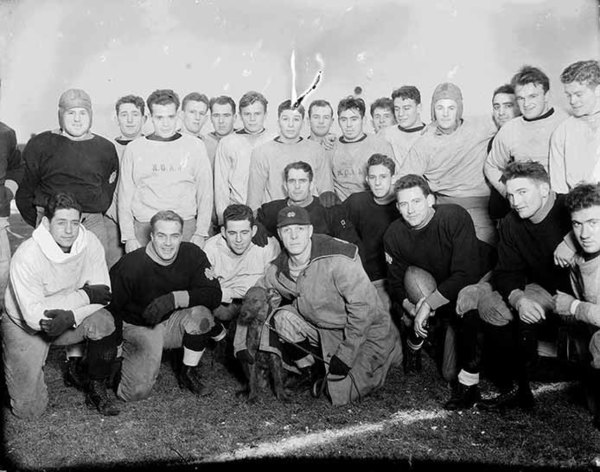

On November 19, 1932, dog breeder Charles Otis donates an Irish Terrier named Brick Top Shaun Rhue as a mascot for the football team, making him the latest in a line of canine precursors (such as Mike the bulldog and the Tipperary Terrences of the Rockne era) to the more familiar Clashmore Mikes of the later 1930s and ’40s. Shaun Rhue (Irish for “Old Red”) proves a bit of a rambler and disappears from campus altogether the following spring.

The University opens LOBUND — the Laboratories of Bacteriology at the University of Notre Dame — in 1935, building upon the work of Professor James A. Reyniers, class of 1928, attracting top scientists and establishing Notre Dame as the world leader in germ-free research, including Morris Pollard’s work combating cancer.

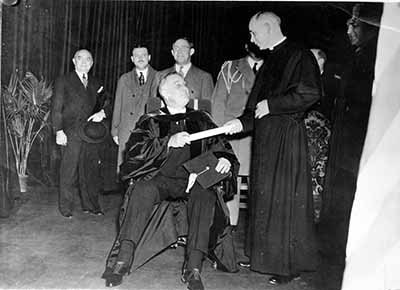

President Franklin D. Roosevelt delivers a speech at the Fieldhouse December 9, 1935, celebrating the establishment of the Philippines as an independent country, and receives an honorary degree, the first in a long but not unbroken line of presidential visits to campus.

Fathers Philip Moore and Leo R. Ward lay out plans in 1936 for a Ph.D. program in philosophy, the first humanities discipline at Notre Dame to ascend to that level of study. The University had begun awarding doctoral degrees in chemistry in the 1920s. Still, writes historian Father Arthur Hope, CSC, “fully ninety per cent of Notre Dame students are undergraduates who have no thought of graduate work.”

The Vatican’s secretary of state, Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, two-and-a-half years shy of his election as Holy Father, stops in at Notre Dame October 25, 1936, during a lengthy airplane tour of the United States. Greeted at Sacred Heart with the “Papal March,” he kneels in prayer at the steps of the altar, receives an honorary degree and gives the students the rest of the day off.

Austrian mathematician Karl Menger leaves the University of Vienna in 1937 to join the faculty at Notre Dame. His appointment begins to put the mathematics department on the international map; it also signals Notre Dame as a safe haven for European academics fleeing or forced to leave by the worsening political climate. Political theorist Waldemar Gurian makes a similar mark on the political science department, founding the influential Review of Politics in 1939.

On February 14, 1936, led by George Ireland and Johnny Hopkins, Notre Dame stuns roundball powerhouse NYU, 38-27, before a record crowd of 19,000 at Madison Square Garden, all but securing the school’s second of two national basketball championships, a title determined at the time by the Helms Athletic Foundation.

March 2, 1939: The pope is a Notre Dame alumnus (see 1936).

Working with their own homemade particle accelerator in Cushing Hall in 1939, Notre Dame physicists become the first to successfully smash atoms using electrons, a first step toward a graduate-level physics program — and involvement in the Manhattan Project three years later.

Knute Rockne, All American premieres at a South Bend movie theater, December 4, 1940, making the “Win One for the Gipper” speech part of American folklore.

The United States Navy sets up shop September 1941, installing several units of the Naval Reserve Officers’ Training Corps. The number of men in uniform on campus rises sharply after December 7 that year. An estimated 11,925 Navy officers would complete their training at Notre Dame between 1942 and ’46.

Monsignor Fulton J. Sheen, host of The Catholic Hour radio program, delivers a nationally broadcast homily from Sacred Heart Church during a Mass to celebrate Notre Dame’s centennial on November 27, 1942.

Physics professor Bernard Waldman begins a leave of absence from the University in March 1943 to work on the Manhattan Project, the research that created and tested the atomic bomb. Aboard a military observation plane when the Enola Gay drops the “Little Boy” bomb on Hiroshima, killing at least 90,000 people, he returns to Notre Dame after the war, serving as dean of the College of Science from 1967 to ’79.

Benefactor Martin J. Gillen dies September 22, 1943, leaving Notre Dame most of the remainder of his estate and expressing his preferences for the University’s use of a prior gift, more than 6,000 acres of land and water near the remote northern Wisconsin hamlet of Land O’Lakes. In 1951 the first whole-ecosystem experiment is performed there, and extensive biological investigations continue today through the University of Notre Dame Environmental Research Center — UNDERC.

Through its October 1, 1943, issue, The Notre Dame Scholastic readers catch up on the career of Sister Mary Aquinas Kinskey, OSF, ’42M.S., “the flying nun,” who is serving as an educational adviser to the Civil Aeronautics Authority and teaching aviation at Catholic University in Washington, D.C. In 1957, the Air Force would cite her for “outstanding contributions” to national security and let her take the controls of a T-33 Shooting Star during a training flight, becoming the first nun to fly a jet.

Brother Canute Lardner, known for his generosity and “a sly sense of humor that was quoted all over campus,” dies February 2, 1946, during the showing of a matinee at Washington Hall, “as unobtrusively as he had lived.”

Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander-in-chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet during World War II, receives an honorary degree May 15, 1946, at the Navy Drill Hall, thanking Father Hugh O’Donnell for sending him “men who had become imbued with more than the mechanical knowledge of warfare.”

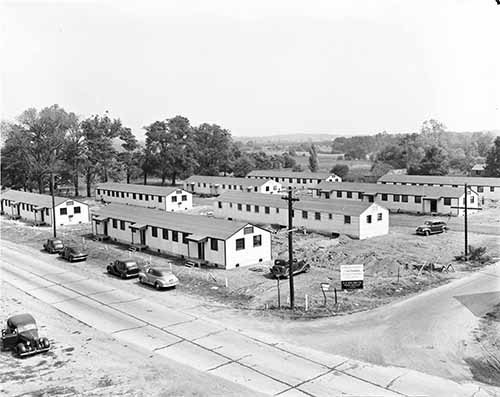

“Vetville” opens in September 1946, as 117 former soldiers and sailors enroll as students on the GI Bill and move their families into 39 former prisoner-of-war barracks reconstructed on campus’ northeastern corner. Soon the housing complex becomes a village with its own mayor, newspaper, paved streets and playgrounds. Another new thing under the Notre Dame sun is the lineup of baby buggies outside Sacred Heart Church on Sunday mornings.

With as much claim to the title “Game of the Century” as any other, the November 9, 1946, contest between Army and Notre Dame is hyped as a battle of unstoppable offenses and quickly turns instead into a clash of titanic defenses, ending in a dramatic and astounding — but scoreless — tie.

The Medieval Institute formally opens February 2, 1947. The inheritor of a “Program in Mediaeval Studies” created in 1933, it is destined to become headquarters for “the largest contingent of medievalists of any North American university.”

On October 25, 1947, Notre Dame v. Iowa becomes the first Fighting Irish football game broadcast on television, but it would be a long time before Father Ted Hesburgh and athletic director Edward “Moose” Krause fulfill their dream of regular TV coverage, much less the exclusive NBC deal.

Notre Dame’s Radiation Laboratory — Rad Lab — is established in 1949 and today is home to the largest concentration of radiation chemists in the world.

Rev. John J. Cavanaugh hands over the keys to his presidential office to Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh in the spring of 1952, along with the responsibility to give a talk that night to campus members of the Catholic Family Movement.

In autumn 1952 the “Milk Riot” erupts, a dining-hall protest against the University’s attempt to reduce milk waste by replacing 8 oz. glasses with 6 oz. glasses. Students raised the impostors as if in a toast to the wild-eyed prefect of discipline as he desperately circled the room in vain, then let the glasses fall to the ground to shouts of “Fire one!” “Fire two!”

Parents, many booking rooms in the brand-new Morris Inn, descend on Notre Dame April 18, 1953, for the first “Parent-Son Day,” an opportunity to “better acquaint students’ parents with the everyday life their sons lead on campus” and not merely with the atmosphere of football weekends, planners say. Expanded and moved to February, the event is eventually renamed “Junior Parents Weekend.”

Father Sorin (well, a 3-foot-tall bronze statue of him) mysteriously returns in June 1953 after a world tour that started the previous Christmas, documented by telegrams and postcards sent from Washington, D.C., Tokyo, the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in London and an audience with Pope Pius XII in Rome. The statue actually had spent the intervening time in a sand trap of the Burke Golf Course and the Chicago home of student August Manier’s girlfriend.

The celebrated Croatian artist Ivan Mestrovic comes to Notre Dame in 1955 and continues until his death in 1962 to sculpt pieces now installed in Europe and America, including Christ and the Samaritan Woman at Jacob’s Well, in front of O’Shag.

Adam Arnold joins the finance department in 1957, becoming the University’s first African-American faculty member and the first to get tenure, teaching at Notre Dame for 30 years. In 2003 the World War II veteran receives the William Sexton Award, given to a non-alumnus faculty or staff person whose life exemplifies Notre Dame values.

In 1957 novelist and short-story writer Flannery O’Connor speaks on campus about faith and fiction-writing: “I have heard it said that belief in Christian dogma is a hindrance to the writer, but I myself have found nothing further from the truth. Actually, it frees the storyteller to observe. It is not a set of rules which fixes what he sees in the world. It affects his writing primarily by guaranteeing his respect for mystery.”

Professor George Craig becomes director of the Vector Biology Laboratory in 1957 and for two decades performs internationally acclaimed research into the genetics of Aedes aegypti, to combat the scourge of mosquito-borne diseases.

In April 1959, the Collegiate Jazz Festival, once described by Time magazine as “the biggest college bash of them all,” fills the old Fieldhouse with a smoking medley of jazz style, launching its run as the nation’s premier jam of its kind.

Tom Dooley ’48, dying of cancer in Hong Kong, writes Father Hesburgh on December 2, 1960, that the Grotto is “the rock to which my life is anchored,” adding, “If I could go to the Grotto now then I think I could sing inside. I could be full of faith and poetry and loveliness and know more beauty, tenderness and compassion.”

Father Ted Hesburgh appears on the cover of Time magazine, February 9, 1962.

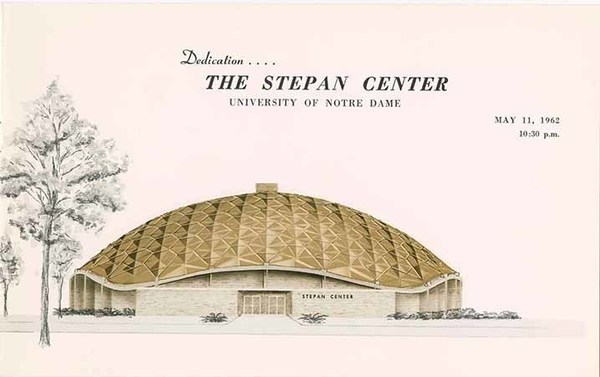

The University dedicates on May 11, 1962, the Stepan Center, the most distinctive of its midcentury steps away from the dominant Collegiate Gothic style of campus architecture in favor of Midcentury Modern.

On February 21, 1963, the annual student-organized Mardi Gras celebration with its casino games, big-prize charity raffle, dances and jazz concerts is cited as one of the top three in the United States . . . maybe on the strength of Duke Ellington’s performance at the Mardi Gras Ball the year before.

The Memorial Library, later renamed the Hesburgh Library, opens its doors for use September 21, 1963, although the building has yet to be formally dedicated and its south face has yet to be decorated with artist Millard Sheets’ iconic Word of Life mural, depicting Christ the Teacher surrounded by saints and scholars, eventually known as Touchdown Jesus.

Invited by local citizens, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. speaks at Stepan Center October 18, 1963, as a fundraiser for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. “The world has shrunk into a neighborhood,” he tells the audience of some 3,000 guests. “Now we must make it a brotherhood, or we will die together as fools.”

Notre Dame sends students to Innsbruck, Austria, in 1964 — its first group of students to study abroad. Today more than 1,200 students study at more than 60 foreign locations annually, while 1,573 international students and scholars came to Notre Dame from 94 countries.

With final passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 imminent, the Illinois Rally for Civil Rights draws a crowd estimated at more than 75,000 people, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh among them as top-of-the-bill speakers. The June 21, 1964, photograph of the two men singing “We Shall Overcome,” hands clasped with each other and with other prominent clergymen, would become an icon of the movement, a print of it hanging in the National Portrait Gallery and a statue inspired by it slated for unveiling in downtown South Bend this year.

The University sues 20th Century Fox in December 1964 to prevent the distribution of John Goldfarb, Please Come Home!, a camp classic centered on a football game between Notre Dame and the fictitious Middle Eastern Fawz University. Father Hesburgh, whose name appears in the novel, objects to the depiction of the Fighting Irish as “undisciplined gluttons and drunks,” but the New York Court of Appeals dismisses the school’s argument, rules in the studio’s favor and the film flops.

Sister Suzanne Kelly, OSB, and Josephine Massyngbaerde Ford become the first women in modern times to receive full-time, academic-year faculty appointments — in 1965.

Lewis Hall is opened August 10, 1965, and dedicated as the first ND residence hall built for women — at that time, mostly religious women pursuing graduate and professional degrees. It would later accommodate lay graduate students before being rehabbed and repurposed as an undergraduate women’s hall in 1975.

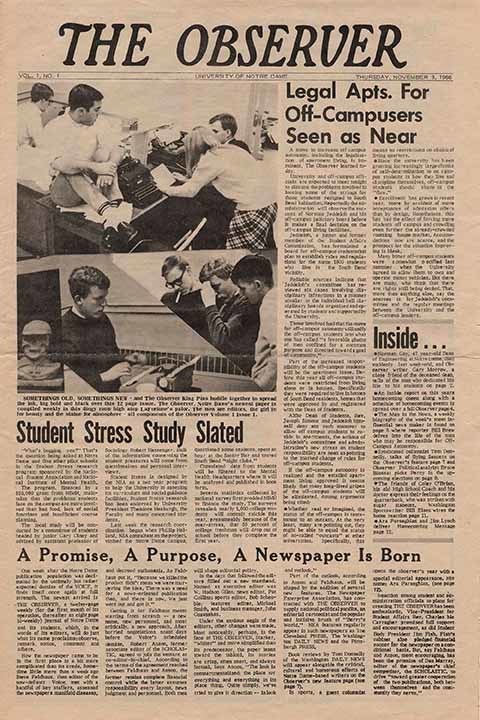

November 3, 1966, the first issue of The Observer boldly claims to be a newspaper meant to appeal to “the liberal . . . a man who is always on special assignments, who eschews the automatic response, the doctrinaire formula,” and who “is wary of ideologies and absolutes.”

In 1967 the rites of spring take form in AnTostal (Irish for “the pageant”) originally a student-initiated festival of joy, competition, silliness, rustic pastimes, cream pies, mud pits and fun. Over the years, it spins off such signature events as the Fisher Hall Regatta and the Bookstore Basketball tournament.

After four days of closed debate in the summer of 1967, the provincial chapter of the Congregation of Holy Cross concludes its deliberations in Sacred Heart Church and announces its decision to transfer ownership of the Notre Dame campus to a predominantly lay board of trustees, and provide legal ownership and governance to a 12-member executive group — the University fellows, composed of six laypersons and six Holy Cross priests. The University’s “Catholic character” will be the focus of scrutiny and debate for decades to come.

In only its second year, the 1968 Sophomore Literary Festival — created and organized entirely by the sophomore class — attracts Norman Mailer, Ralph Ellison, Kurt Vonnegut, Joseph Heller, William F. Buckley Jr. and write-ups in both the Saturday Review and The New York Times.

In 1969 students, faculty and staff hold a peace rally at “the circle,” then march to the ROTC Building where they plant wooden crosses to commemorate each Notre Dame graduate killed in the Vietnam War before assembling near the Memorial Library for a Mass for peace.

In January 1969, the Alumni Association takes charge of Andre House on Eddy Street, once a house of formation for Holy Cross brothers and more recently the site of the Faculty Club. Drinking-age seniors soon take over, both in the sheer numbers of drinking, dancing, pool-playing patrons and in business operations. By 1974, “Alumni Club” would be out and “Senior Bar” would be in.

On February 7, 1969, St. Joseph County police raid Nieuwland 127, seizing a banned film that students attempt to show during the University-approved “Pornography and Censorship Conference.” The ensuing altercation marks the first violent confrontation on campus between students and police in Notre Dame history.

Student opposition to Dow Chemical and the CIA recruiting on campus in 1969 erupts in a confrontation that results in the expulsion of five students and the suspension of five others — known as the Notre Dame Ten — who were in violation of Father Hesburgh’s previously announced 15-minute rule.

In 1970, outraged by the military invasion of Cambodia and horrified by the killing of students at Kent State University and Jackson State University, students hold protest rallies, attend Masses for peace and go on strike. Father Hesburgh issues a public statement condemning the Vietnam War, and 1,000 students collect 23,000 signatures from local residents expressing their opposition to the war.

Notre Dame’s Ecumenical Institute for Advanced Theological Studies, established by Father Hesburgh at the request of Pope Paul VI, opens its doors in 1971 at Tantur in Jerusalem to try to bring peace and understanding to the ancient site of ages-old religious, cultural and political hostilities.

“Merger hopes killed; speculation rampant” reads the November 20, 1971, front-page headline in The Observer, reporting the decision not to move forward with the proposed marriage between Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s College.

On April 21, 1972, “The Family” wins the first “Bookstore Hysteria Tournament,” the original round of Bookstore Basketball — proclaimed the world’s largest five-on-five outdoor basketball tournament by the Guinness Book of World Records in 1983. It has only grown larger since.

Crowned and robed R. Calhoun Kersten, aka “King,” aka “Prime Mover,” wins the 1972 student body presidential election with a cat named Uncandidate as his running mate and a platform advocating oligarchy, consistent drug quality and the distribution of scholarships by lottery.

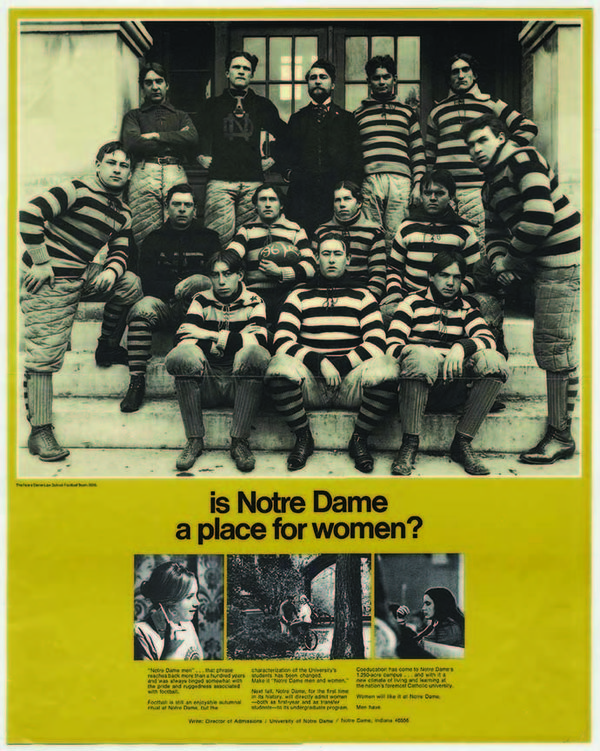

On September 6, 1972, female Notre Dame undergraduates take their seats in classrooms all over campus for the first time — and gamely try to reply when repeatedly asked to explain the woman’s point of view.

Sister Isabel Charles, O.P., named in 1973 to lead the College of Arts and Letters, becomes Notre Dame’s first female dean. She serves until 1981.

The Fighting Irish hoopsters, coached by Digger Phelps, end UCLA’s 88-game winning streak with a dramatic win on national TV on January 19, 1974.

Frank O’Malley ’32, bachelor don, beloved teacher, literary figure and legendary avatar of the liberal arts education, dies on May 7, 1974.

Sister Jean Lenz, rector of Farley Hall, confronts a mob of some 100 streaking men at the door of the women’s residence hall just as a purloined detex card grants them entrance. She disperses the crowd by shouting, “You’re not coming in here like that!”

On New Year’s Day 1979, chilled by the worst ice storm in Dallas history, Joe Montana, fighting the flu with chicken soup at halftime, leads the Irish back from a 34-12 fourth quarter deficit by throwing the winning touchdown on the game’s final play. A jubilant Ted Hesburgh could be seen conducting the band after Notre Dame’s 35-34 win over the University of Houston.

The Snite Museum of Art is dedicated in November 1980, tripling the University’s exhibition space.

The first issue of Catholicism in Crisis, a monthly journal edited by Notre Dame’s Jacques Maritain Center, is published in January 1983. Its purpose, says editor Ralph McInerny, the Grace Professor of Medieval Studies, is “to provide a place for Catholic lay people to speak out on a variety of contemporary issues, applying Catholic principles to items in dispute.”

The Center for Social Concerns is established in 1983 to coordinate student volunteer programs dedicated to experiential education and social justice. It is described by Msgr. John J. Egan, director of Notre Dame’s Institute for Pastoral and Social Ministry, as “one of the most important steps that the University has taken in relation to its Catholicity.” The center’s first home is the former WNDU studios.

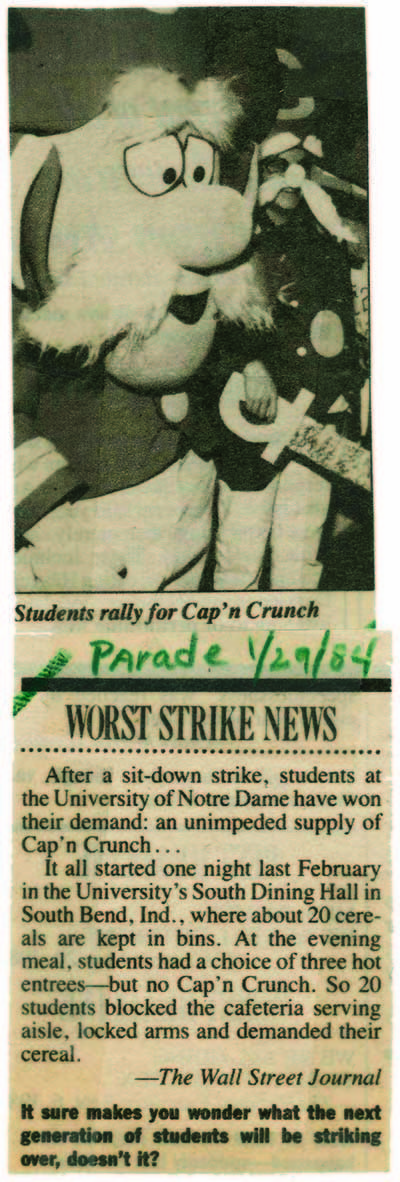

Cap’n Crunch comes to campus October 21, 1983, to supervise an eating contest featuring the breakfast cereal, an event organized by Notre Dame and Quaker Oats officials after sit-ins the previous February protested the cereal’s sudden removal from the dining halls.

More than 2,000 students fill the Main Building April 18, 1984, tossing rolls of toilet paper and empty beer cans down from the balconies and shouting down Dean of Students Jim Roemer, all to protest a new alcohol policy banning private parties, hard liquor and underage drinking.

September 1985: How many students does it take to set the world record for the largest game of musical chairs in the history of the universe? Exactly 5,151.

About 500 students, protesting apartheid in South Africa, gather on the steps of the Main Building in October 1985, calling for the University to divest of its investments in companies doing business there. Father Hesburgh tells the crowd the University is pursuing more effective strategies to end institutionalized racism.

1986: Stonehenge erected. Also known as a war memorial honoring patriots and peacekeepers.

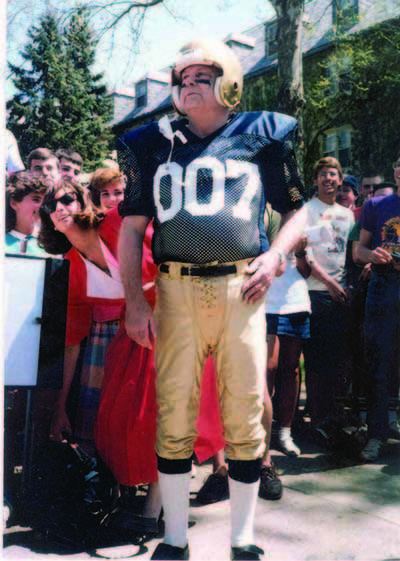

Preceded by a marching band and wearing full football regalia (uniform number 007) Emil T. Hofman (he of the Friday quiz fame) proctors his final final exam in May 1987, after 35 years of teaching students about the elements of chemistry.

In April 1991, about 100 students, armed with pillows, blankets, radios and food, gather outside the registrar’s office on the second floor of the Main Building to begin their 11-hour sit-in to demonstrate their dissatisfaction with University diversity efforts. They are Students United for Respect — SUFR, pronounced “suffer.”

Film crews, actors, cameras, producers, gaffers, grips and student extras turn campus into a movie set in 1992 to cinematically re-create the story of Daniel E. Ruettiger ’76. Ru-dy!

The Notre Dame women’s soccer team wins the national championship in 1995, capturing the title again in 2004 and 2010.

The Center for Zebrafish Research opens in 2000, examining the regeneration of retinal neurons in some 200,000 zebrafish in pursuit of therapies to treat human neurological diseases, such as macular degeneration, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

Muffet McGraw’s women’s basketball team goes 34-2 and captures the 2001 national championship.

Thousands of students gather on the South Quad on September 11, 2001, as Father Monk Malloy, CSC, celebrates Mass in honor of the victims of that day’s terrorist attacks.

Taking the stage a month after the 9/11 attacks, Bono greets the raucous crowd inside the Joyce Center: “The heart is a bloom, it shoots up through the stony ground.” The U2 concert that follows on this October 10, 2001, night is one for the ages.

In 2006 the University announces a major construction project south of campus. Eddy Street Commons will include housing, retail, restaurants and commercial enterprises in an attempt to create a “college town atmosphere” and bridge to the South Bend community — long declared off-limits to the impressionable Catholic lads schooled on the sequestered campus.

The University opens Innovation Park in 2009 to help convert the fruits of research into commercial applications and ventures.

Established in 2009, Notre Dame’s center dedicated to developing life-saving treatments for rare and neglected diseases is renamed in 2014 because of substantial support from the Boler and Parseghian families.

Notre Dame welcomes President Barack Obama, the nation’s first African-American president, to commencement May 17, 2009, eliciting impassioned demonstrations of disapproval. In their addresses Obama and University President John Jenkins, CSC, call for reasonable dialogue in resolving differences of faith and culture. “Easing the hateful divisions between human beings,” says Jenkins, “is the supreme challenge of this age.”

In October 2009 about 115 members of America’s oldest university marching band join the rock group OK Go to produce a video of the pop song, “This Too Shall Pass.” The two bands also collaborate on the track for OK Go’s album, Of The Blue Colour of the Sky, released in January 2010.

The University establishes the Keough School for Global Affairs in 2014 to apply scholarship in service to the common good. With an emphasis on integral human development, the Keough School brings together seven distinct centers and institutes that have long supported the University’s tradition of international engagement, education, research and policy-making.

Notre Dame President John Jenkins, CSC, members of his leadership team and the University’s Board of Trustees meet with Pope Francis on January 30, 2014, during an hour-long audience in the Apostolic Palace. “From its founding,” the pope says, “the University of Notre Dame has made an outstanding contribution to the Church in your country through its commitment to religious education of the young and to serious scholarship inspired by confidence in the harmony of faith and reason and in pursuit of truth and virtue.”