Dr. Frankenstein’s big green monster always takes up a prominent place in society around Halloween, but in 2018, both monster and doctor (and the novel that inspired it all) zombie-walked their way into the mainstream all year long. Mary Shelley’s famous book turned 200 last year, and the bicentennial was celebrated in almost too many forms of media to count.

Photo by Matt Cashore '94

Photo by Matt Cashore '94

Frankenstein-themed articles, reports and special issues appeared everywhere from The New York Times to Parade. A Frankenstein musical — the latest in a long line — debuted off-Broadway and a Dr. F-inspired puppet show took the stage in Chicago. A Frankenstein-tinged subplot animated Chilling Adventures of Sabrina, Netflix’s viral-hit Sabrina the Teenage Witch reboot. In the United Kingdom, a commemorative two-pound coin marked the book’s anniversary.

Unsurprisingly, universities got in on the anniversary action, too — and Notre Dame was the celebration’s beating, built-from-scratch heart.

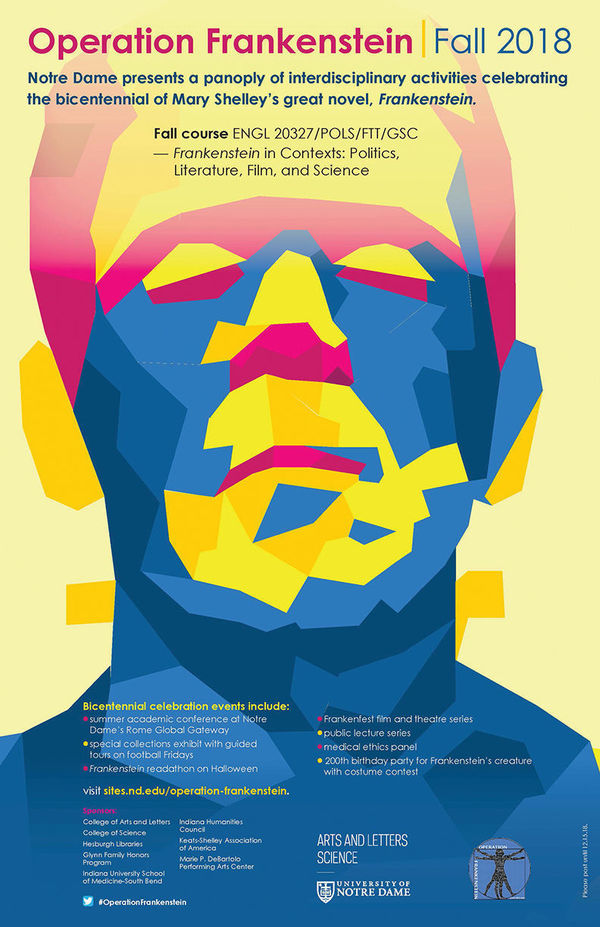

“Operation Frankenstein” boasted a film and lecture series, a semester-long Special Collections exhibit, a new Frankenstein-themed class and an international conference on the novel held at the University’s global gateway property in Rome.

“There have been many conferences on Frankenstein this year, but I think ours was one of the most fun and engaging,” says Eileen Hunt Botting, professor of political theory and co-chair of Operation Frankenstein. One of the most appealing parts of the novel, Botting says, is how many fields of study can draw inspiration from it — from literature and political science to genetics, bioethics and even film studies. At many universities, the focus was singular, devoted to just one of the impacted fields. Notre Dame went broad, drawing scholars from anthropology, medicine, law, psychology, neuroscience, literature, history, film, philosophy and political science.

“The range of scholarship was impressive,” notes Botting, a scholar of the political thought of Shelley’s time, “and the risk-taking that came with that was as well.”

Botting and her co-organizer, English professor Greg Kucich, an expert in British Romanticism and women’s writing, hatched the idea of an international conference for the bicentennial back in 2014, and the event went essentially as they’d hoped. Two other conferences — one in Bologna and another at Smith College in Massachusetts — cited it as inspiration for their programs, and at least two scholars found publishers for new works based on their Rome presentations.

More surprising, Botting and Kucich say, was the response back on campus.

“I would not have guessed that it would be on this level that it seems to be on in the popular imagination,” Botting says. Operation Frankenstein screened eight Frankenstein-related films in the DPAC’s Browning Cinema during the fall semester — including the 1931 Boris Karloff adaptation, Mel Brooks’ Young Frankenstein and a National Theatre Live production starring Benedict Cumberbatch — and the seats were generally filled, with both students and area residents.

Shelley’s work poses a lot of big questions, Botting adds, and the turnout at these film adaptations shows a widespread desire to engage them.

Central, says Kucich, is the question of creation. “Who creates human life? What is human life? Who is our creator? Those are huge metaphysical issues that come up in the novel.”

If the proliferation of public tributes is any indication, these questions resonated in 2018. But Frankenstein’s fundamental themes fit particularly well at Notre Dame, where ethics and Catholic social teaching sit at the center of the campus ethos.

The tale of the doctor and his creature, Botting says, forces us to consider what it means to be human. Frankenstein’s monster is humanlike, but was assembled in a laboratory — does he make the cut? If not, what makes him different from a person with an artificial knee or a 3-D printed heart valve? These nuances are harder to articulate than they may initially seem.

“I think it says a lot about Notre Dame,” Botting says, “that [it is] a Catholic university that takes tough questions about the ethics of science and technology really to be at its core.” Some Catholic institutions, she says, may try to shy away from such questions, for fear that the answers — or even the asking — may run counter to their mission. Not so at Notre Dame. “I actually find the opposite here, that there’s been this really admirable push to go straight to those questions, rather than to avoid them.”

If the monster makes us consider who is and isn’t human, the figure of Dr. Frankenstein begs an even bigger question — who gets to decide? In a world where you can build a baby in a test tube, or alter the sequence of the human genome, or instill a genius-level IQ in a computer, whom do we entrust with that power? How do we know when it has gone too far?

“All of those questions, I think, are in everyone’s minds,” Botting says. “So in some ways the novel’s coming into its own.”

Shelley was only 18 years old when she began writing Frankenstein, living in a world without electric light or the telegraph, let alone the fledgling genetic experiments that would emerge in the mid-1800s. It’s impossible for her to have known the relevance that her little horror story would have to technologies that would emerge in the centuries after her death. But Botting posits that she may have had some idea.

“Could she have known that she could have spoken to our moment so clearly? I don’t think so. I don’t think any author could know that,” she says. “But do I think that she was a futuristic author, somebody who was really interested in this question of influencing the future, or coming up with something that would really blow people’s minds in her own time and in the future? Yes, I do.”

The last screening in the fall semester’s Frankenstein film series was the 1997 sci-fi flick Gattaca. In it, society is divided into two castes — the “valids,” who are created through genetic engineering, and the “invalids,” who are not. Barely two decades ago, the story was pure science fiction. Today, it’s a not-at-all-impossible potentiality, and one that scientists and ethicists must contend with every day. No green man with bolts in his neck appears in Gattaca, but it’s clearly a descendant of Shelley’s masterpiece. It, like the novel, asks: What can go wrong when human beings play God?

“There are many ways in which the novel can be read,” Botting says. “Historically for sure, rooted in contemporary debates on science, or the politics of the French Revolution. Those are all valid readings.

“But there is also a way in which [Shelley] takes all those historical ingredients and she literally pushes us to look far, far ahead. Even for us to look far ahead in our time — not solely people in her time, but for us to keep looking ahead.”

Operation Frankenstein 3018, here we come.

Sarah Cahalan is an associate editor of this magazine.