Library of Congress

Library of Congress

We have gone through serious experiences since my last letter to you. The influenza was almost the death of all human joy. — Letter from Notre Dame President Rev. John W. Cavanaugh, CSC, to theologian Francisco Marín-Sola, August 26, 1919

The first campus death that autumn was Robert “Bobby” Corrigan’s on October 13, 1918.

“On Sunday evening Bob Corrigan died from pneumonia and the boys of Carroll Hall lost a playfellow who will be sadly missed,” read the obituary in The Notre Dame Scholastic a few days later. Bobby Corrigan was one of the minims, young boys attending the boarding school on campus in that era.

Other deaths would follow.

As the University adapted to the spring 2020 campus shutdown and shifted to online classes as a result of the coronavirus pandemic, it was a reminder of the deadly contagion that began to sweep the globe more than 100 years earlier. That disease came to be known as the Spanish influenza, and it killed large numbers of adults ages 20 to 40, in contrast to the ordinary flu that typically strikes infants and the elderly the hardest.

The Spanish flu circled the globe during the final months of World War I, which ended in November 1918. Flu and pneumonia outbreaks continued around the world into the first months of 1920. In total, the pandemic may have killed more than 50 million people worldwide — more than the number of military and civilian deaths attributed to the war itself. In the United States, about 28 percent of the population became infected and more than half a million people died.

The disease spread in part because of troop movements to military camps around the U.S., on ships to and from Europe, and across European battlefields. In Indiana, the worst of the pandemic occurred in October 1918. During that month, South Bend’s newspapers printed long columns about local people who were struck ill or had just died of influenza or pneumonia.

The world’s first known cases were reported in March 1918 at Fort Riley, Kansas. By the end of the month, more than 1,100 men on the base were ill. Then, according to British science writer Catharine Arnold, author of Pandemic 1918, the illness seemed to fade as quickly as it had arrived.

A second round of the disease started in August. It was more widespread and deadly, and often complicated by pneumonia. It hit Great Lakes Naval Training Station, 30 miles north of Chicago, on September 11. By the end of the first week, 2,600 sailors at the camp were ill.

The initial cases in the South Bend area were reported soon thereafter. The South Bend News-Times reported the first local death, that of a one-year-old boy, in Mishawaka on September 27.

Many believed the unseasonably warm weather that autumn contributed to the persistence of the outbreak. “The month of October was particularly pleasant. Had it been unpleasant, had it only turned cold, said many, it would have been more healthful,” the historian Rev. Arthur J. Hope, CSC, a member of the Class of 1920, wrote in Notre Dame: One Hundred Years, published in 1943. “As it was, Spanish Influenza was sweeping through the country. It was the opinion of some that the germ would have been killed by cold weather. But October was unusually balmy and warm. Students fell ill by the scores. Classes had to be abandoned.”

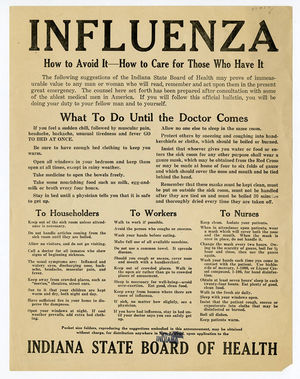

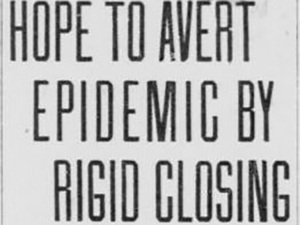

On October 11, Dr. Emil G. Freyermuth, South Bend’s city health officer, issued an order forbidding all public gatherings until further notice. All schools, theaters, clubs and religious institutions were closed. Public funerals, meetings, dances and other events were canceled. By that time, news reports tallied at least 6,000 cases of the flu in Indiana. Some 88,000 new cases were reported that week across the country.

In South Bend, the shutdown would continue until November 9. While restaurants weren’t required to close, the city ordered streetcars to operate with all windows open, in hopes of preventing the flu’s spread. Meanwhile, the Indiana state board of health required the homes of flu patients to be marked with a “QUARANTINE” sign.

Throughout the fall, The Notre Dame Scholastic published news about alumni and those relatives of faculty and Holy Cross priests who had died elsewhere of influenza or pneumonia.

Father John W. Cavanaugh, CSC, Notre Dame’s president since 1905, sought to downplay the campus illnesses, hoping to avoid a panic. He spoke to the student body during the annual Columbus Day celebration on October 14. “First he made it very plain there is no influenza whatever at Notre Dame. Then, for the protection of the University, he announced that permission to go to the city can not be had,” the Scholastic reported.

On October 20 came the death of Sister M. Claudine, a nurse who had been caring for students in the college infirmary. Three days later, Cavanaugh issued a letter to the campus community reporting the deaths of four students and the illnesses of at least 50 others, but still saying the outbreak wasn’t a major problem. In addition to Bobby Corrigan, the priest announced the deaths of students Lester Burrill, William Conway and George Guilfoyle. “In general, we have had very little evidence of the presence of the so-called Spanish Influenza,” he wrote. “This may be due to the fact that the Notre Dame boy, as a rule, is in exceptionally good shape physically.”

Cavanaugh’s underestimation of the threat mirrored local concerns that not all cases were being reported to the health department. Based on interviews conducted with 14 physicians on October 25, state health official John Willett declared an epidemic in South Bend, with at least 750 active flu cases — far more than the number reported to the city health office.

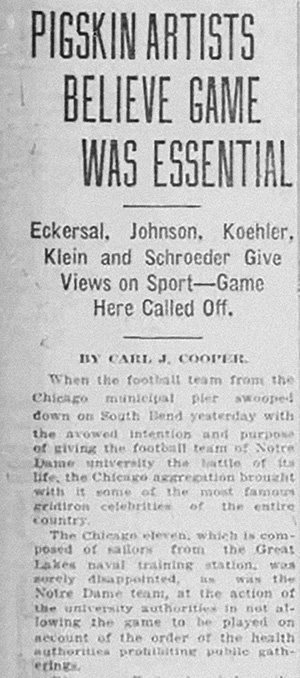

The Notre Dame football team — led by new head coach Knute Rockne and including star player George Gipp — canceled or postponed three October games because of the ban on public gatherings, including a match with the team from Great Lakes Naval Station. Gipp, for his part, remained healthy during the outbreak, but died two years later of strep throat and pneumonia.

Newspaper advertisements touted remedies that claimed to combat the flu. Some urged people to use Vicks VapoRub at the first sign of a cold. Others advertised a popular patent medicine called Peruna, which was mostly alcohol and water.

In all, Indiana physicians treated nearly 59,000 flu cases in October 1918, with St. Joseph County accounting for at least 1,500. By mid-November, flu diagnoses were still being reported in South Bend, but they appeared to be milder.

At Notre Dame, classes resumed October 28 after a lapse of more than a week. “This week marks, apparently, the end of the influenza epidemic at Notre Dame,” the Scholastic reported on November 2. “Distressing as this was for a time at the University, it was nothing here in its ravages as at other institutions. No new cases have been reported now for more than a week, and the isolation hospital is practically cleared.”

The epidemic continued to take lives across the country. Cavanaugh’s only sister died of pneumonia on November 5 at her home in Ohio. The priest was at her bedside.

Notre Dame resumed its football schedule in November, playing its final five games to finish the 1918 season at 3-1-2.

On November 16, cadets in Notre Dame’s branch of the Students’ Army Training Corps, a precursor to ROTC that allowed young men to receive military training while continuing their college classes, were permitted to leave campus to participate in a downtown South Bend parade celebrating the armistice that had been declared November 11. An estimated 50,000 people participated in the gathering, according to newspaper reports.

By November 20, Indiana reported 3,386 deaths statewide from the influenza and pneumonia outbreak. Among Indiana cities, South Bend, with 152 of the 185 deaths counted in St. Joseph County, was second only to Indianapolis, where 379 people died.

The University had about 1,500 students in fall 1918. Notre Dame shared in the international pain and sacrifice. “We had more than two hundred cases of the disease,” Cavanaugh wrote to his friend Francisco Marín-Sola the following summer, “and there were nine deaths among the students.”

Margaret Fosmoe is an associate editor of this magazine.