A century ago today, Notre Dame and the nation grieved the death of George Gipp.

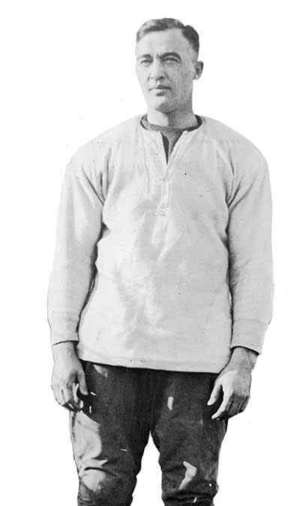

It didn’t seem possible that Gipp, the vibrant star halfback of coach Knute Rockne’s undefeated 1920 football team, could be gone. A denizen of South Bend gambling dens who spent most of his college years living off his winnings in a local hotel rather than in a campus residence hall, he could work the same magic with a pool cue, cards or dice in his hands as he did with a football.

Gipp died at 3:23 a.m. December 14, 1920 at St. Joseph Hospital in South Bend. He was 25. His passing stunned his family, classmates, sportswriters and football fans across the country.

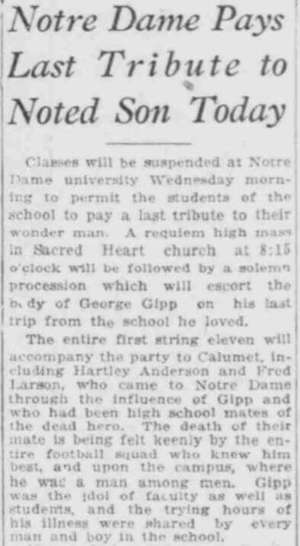

At Notre Dame on December 15, flags flew at half staff and classes were canceled so students could attend a Requiem Mass in Sacred Heart Church. Hundreds of students then accompanied Gipp’s coffin to the New York Central train station in South Bend, where it would be transported to his hometown of Laurium, Michigan. His teammates led the solemn procession, South Bend newspapers reported, walking in their football formation — with Gipp’s spot left vacant.

Gipp’s illness was first reported in late November. He didn’t accompany the team to the season’s final game against Michigan Agricultural College (today’s Michigan State University) in Lansing on Thanksgiving.

His ailment initially was described as tonsillitis, then pneumonia, then strep throat — or perhaps a combination of all three. This was in the era before penicillin and other antibiotics were available, and treatment options were limited. Daily updates appeared in the newspapers, reporting Gipp was failing, then doing better, then fighting for his life.

Gipp’s performance on the football field had led the gold and blue team (Notre Dame hadn’t yet adopted the Fighting Irish as a formal nickname) to 19 straight wins in the consecutive unbeaten seasons of 1919 and 1920.

The 1920 team outscored opponents 250-44. During his last two years, Gipp rushed for 1,556 yards (averaging 7.5 yards per carry), passed for 1,436 yards (over 20 yards per completion), intercepted six passes and kicked 20 PATs. He held the school’s career rushing record with 2,341 yards for more than 50 years. He died shortly after he was selected by Walter Camp as Notre Dame’s first All-American.

“To stop Gipp on the run was about as easy as damming Niagara, and an opposing runner needed an aeroplane to get to him,” a student reporter wrote in the Notre Dame Scholastic a few days before the star’s death.

Gipp was born and raised in Laurium, in copper mining country on the Keweenaw Peninsula in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Gipp dropped out of high school, and for the next several years drove a taxi, played semi-pro baseball and polished his billiards game in his hometown. One of his baseball friends, Wilbur “Dolly” Gray, had been an outstanding catcher on the Notre Dame baseball team in 1913-1914, and he urged Gipp to apply to the school. He was admitted as a “conditional freshman” because he hadn’t graduated from high school, which wasn’t unusual in those days.

Gipp headed to Notre Dame with the intention of playing baseball, his favorite sport. Rockne, then coach of the freshman football team and an assistant to varsity head coach Jesse Harper, saw Gipp kick a football and recruited him to the gridiron.

Gipp enrolled in 1916 at age 21, working a job as a campus waiter and earning extra money playing pool and cards in downtown South Bend, author Murray Sperber reported in his 1993 book, Shake Down the Thunder: The Creation of Notre Dame Football. Gipp was skilled at cards and pool, so good that he mostly lived in a room at the luxurious Oliver Hotel in South Bend after his first semester, according to Sperber’s research. (Gipp also was a talented dancer, reportedly winning a gold watch in a dance contest.)

“Gipp was a born gambler, on the gridiron and off,” his 1919 roommate and teammate Arthur “Dutch” Bergman later recalled, according to a 1978 Notre Dame Magazine article. “Nobody around South Bend could beat him at faro, craps, pool, billiards, poker or bridge. He studied the percentage in dice rolling and could fade those bones in a way that had a professional dizzy. At three-pocket pool, he was the terror of South Bend parlors.”

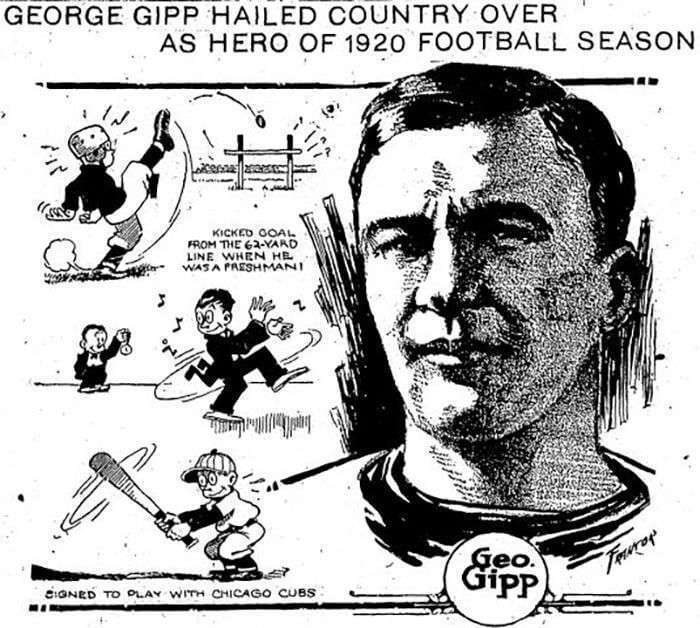

Gipp played the 1916 season on the freshman football squad. On October 7, 1916, during a game against Western State Normal College (today’s Western Michigan University) in Kalamazoo, he kicked a 62-yard field goal.

But he was always more enthusiastic about baseball. During Gipp’s hospitalization, Chicago Cubs manager Johnny Evers offered Gipp a contract to play beginning the next summer.

Gipp was a less than diligent student, prone to cutting classes. He was expelled in the spring of his junior year, but that decision was soon reversed after 80 prominent South Bend citizens petitioned University President Father James A. Burns to readmit the gridiron star. (He played five seasons because the influenza pandemic of 1918 canceled many college games and players were permitted an extra year of eligibility.)

Misconceptions about Gipp have spread over the years.

Despite the campus legend that Gipp’s ghost haunts Washington Hall, there is no evidence that the star player was locked out of his dorm and slept overnight on the steps of the building, thus contracting his fatal illness.

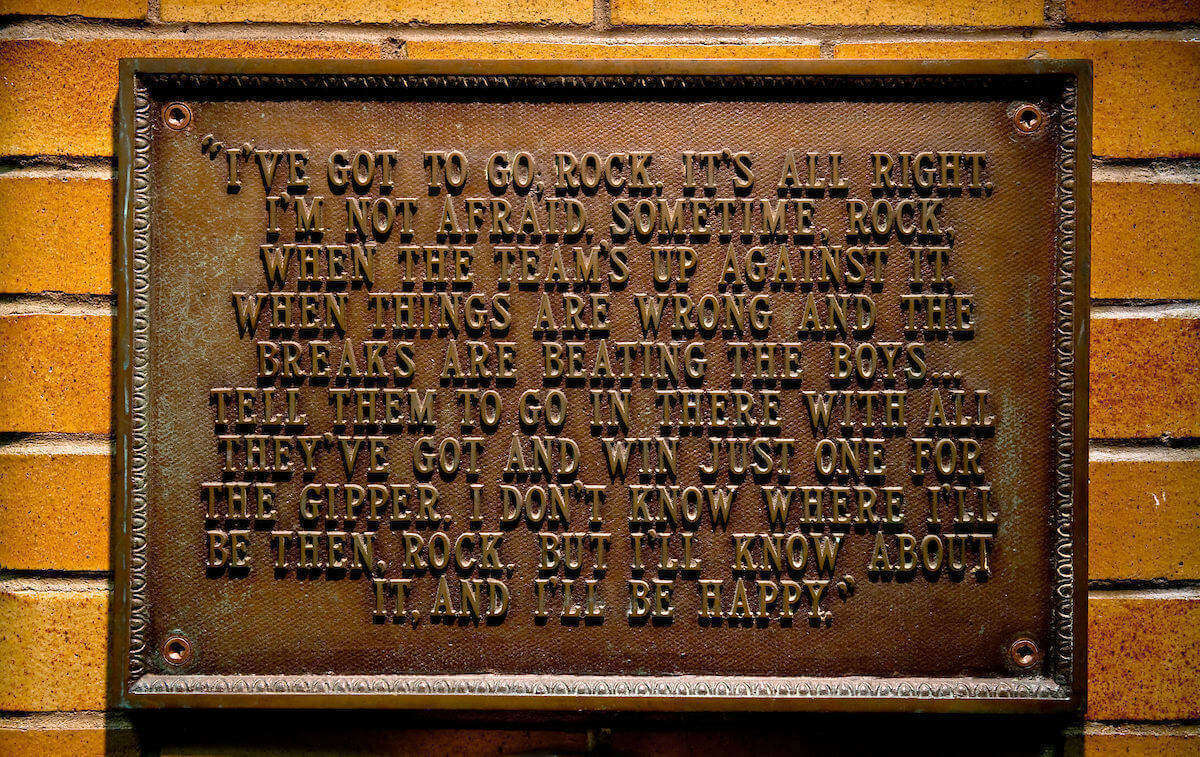

And then there’s Rockne’s famous “Win One for the Gipper” speech, which lives on in college football lore. The Fighting Irish were playing Army on November 10, 1928 at Yankee Stadium in front of a crowd of 78,000. At halftime, Rockne recounted for his players the story of Gipp’s tragic death eight years earlier — and what he told the team was the star player’s deathbed request.

Rockne said the dying Gipp told him that someday, when Notre Dame was down and desperate for a victory, the coach should ask the team to “go in there with all they’ve got and win just one for the Gipper.” The speech rallied the Irish to a 12-6 victory over Army. (A plaque with Rockne’s complete speech hangs in the Irish locker room at Notre Dame Stadium.)

There’s no evidence Gipp ever made such a request of Rockne, who had never mentioned it before 1928, according to Sperber. And nobody remembered the star player in his lifetime being called “the Gipper.”

The speech was immortalized after Rockne’s own 1931 tragic death in the 1940 feature film Knute Rockne, All American, in which Gipp was played by actor and future President Ronald Reagan.

“I’ve always suspected that there might have been many actors in Hollywood who could have played the part better, but no one could have wanted to play it more than I did. And I was given the part largely because the star of that picture, Pat O’Brien (who portrayed Rockne), kindly and generously held out a helping hand to a beginning young actor,” Reagan said during his address as Notre Dame’s 1981 commencement speaker. O’Brien attended that commencement as well, receiving an honorary degree along with his former co-star.

The tale of Gipp’s supposed request and Rockne’s “Win One for the Gipper” speech to the team was recounted in a retrospective video.

Gipp’s story and legacy was kept alive over the years by sportswriters, including Francis Wallace ’23, later a broadcast commentator and author of several books, including a 1960 Rockne biography. Wallace wrote the New York Daily News article reporting Rockne’s halftime Gipper speech to the team.

After a funeral service in his hometown, Gipp was buried in Lakeview Cemetery overlooking Lake Superior. Because of heavy snowfall, the casket was transported five miles to the cemetery on a horse-drawn sled.

“George Gipp 1895-1920” reads the simple gravestone.

Margaret Fosmoe is an associate editor of this magazine.