University of Notre Dame Archives

University of Notre Dame Archives

In an iconic photograph from The Observer of September 15, 1972, a large banner proclaiming “We’re Glad You’re Here” hangs above the doors of South Dining Hall while students gather for a campus picnic to celebrate the beginning of coeducation.

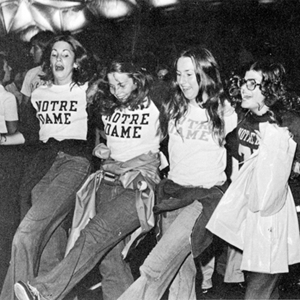

Some 365 female undergraduates enrolled at the University of Notre Dame that first autumn, and their arrival on a campus that for 130 years had served men almost exclusively could hardly have felt natural. Not only were those pioneers an obvious and distinct minority in an undergraduate student body of 6,722, but the tradition-laden institution had been converted for their arrival in a hasty nine months. Notre Dame had determined to pursue coeducation on its own only after merger plans with neighboring, all-female Saint Mary’s College fell through the previous November. Had the welcome of women been unanimous — which it wasn’t — the task of getting campus and classroom ready would hardly have been seamless.

The change took some getting used to.

Today, campus life has largely normalized for female undergrads, but not as fully as one might expect after a half-century. In some ways, Notre Dame still feels like a men’s institution. Much of this could be attributed to the disproportionately low number of women on the faculty and in the upper levels of the University’s administration, although each college and the Law School have had female deans. Less measurable is the sense that women have had to find their place here, to make room for themselves at an institution steeped in male legacies.

Still, female students excel in the classroom, hold leadership roles in all areas of campus life and win their share of victories and national championships in athletic venues. Women have embraced and adapted many Notre Dame traditions — see the Baraka Bouts, in existence since 1997, a women’s boxing competition modeled on the men’s Bengal Bouts.

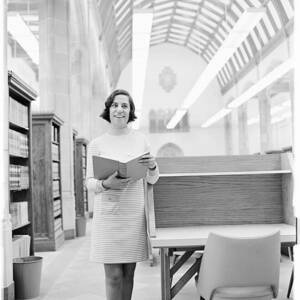

There were, of course, women at Notre Dame before 1972. Female students, mostly religious sisters, had earned degrees as far back as 1917.

Edwina Scanlan O’Toole ’64M.S. enrolled for her master’s degree in mathematics at the urging of one of her college professors, a nun who had earned a Notre Dame doctorate in the 1950s.

It was rare to cross paths on campus with another woman in those days. Female students and employees were required to wear skirts or dresses — no slacks. O’Toole’s classmates and professors were all men. One professor told her that women only attended college to find a husband.

After graduating, O’Toole worked at Notre Dame for several years as an associate research professor. One day, she went to a campus office that offered small loans to students and employees. She was told the program didn’t serve women, and she would need to return with her husband.

Despite such impediments, she says, “I had no regrets. I loved attending Notre Dame.”

Mary Davey Bliley ’72 was the sole woman who received a Notre Dame bachelor’s degree at commencement the spring before coeducation. After the collapse of the planned merger of Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s, Bliley was granted permission to complete her ND degree.

She was the only female student in her business classes. Most of her male classmates were welcoming, but one male professor greeted the class each day with, “Good morning, gentlemen.”

“I didn’t really care, because I knew I was going to get that Notre Dame degree,” she recalls. Bliley’s experiences prepared her for challenges she later faced during a long career in investment banking, where she found herself educating her bosses about the need to accept women in the workplace. One manager told her he didn’t hire women on the trading desks, because they were too distracting. Bliley says Notre Dame taught her a lasting lesson: “Believe in yourself, work hard and you can do it.”

In the fall of 1972, Congress had sent the proposed Equal Rights Amendment to the states for ratification. Title IX, the landmark gender-equity law that assured women equal access in education and expanded opportunities for girls and women in sports, had taken effect that summer.

In the early years of coeducation, the number of female students was restricted while the University converted residence halls to accommodate their growing numbers. Admission was more selective for women than men. The higher hurdle meant Notre Dame women were often considered brainier than their male counterparts. They were also stereotyped as more athletic and less feminine than women at Saint Mary’s and other women’s colleges.

“Little did I know by applying that I was going to be one of the lucky ones to get in,” recalls Carol Latronica ’77, who retired in May after eight years as rector of Welsh Family Hall.

As a student, Latronica lived in Farley Hall. The bathrooms still had urinals, which the women decorated with flowerpots. During freshman phys ed, she and one other female student found themselves in swimming suits in the Rockne Memorial pool with about 70 male classmates. She didn’t have a female professor until her junior year.

Latronica also faced the discomfort of the dining hall, where men sometimes held up number signs rating women on their looks. After the “Battle of the Sexes” — a nationally televised 1973 tennis exhibition match between Bobby Riggs and Billie Jean King, which King won — some female students decided to turn the tables on the men’s traditions of streaking and panty raids and conduct a “jock raid,” pilfering jock straps from a men’s residence hall. The men ended up tossing the women into the library reflecting pool.

Such obstructions helped Latronica forge a strong commitment to women’s leadership, which she applied in a long career as a teacher and counselor. “You always had to prove yourself, and you had to always work a little bit harder to get recognized and get the same things that the men got,” she says.

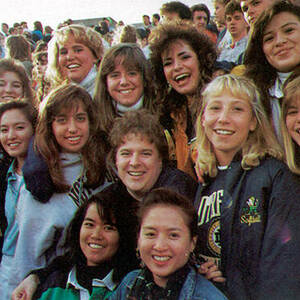

When Latronica returned to Notre Dame as an employee in 2014, campus had changed dramatically. Women made up nearly half of the student body, a far cry from her undergrad days. They’re now involved in every aspect of campus life, she says, which makes for a vibrant student experience.

As a rector, Latronica dedicated herself to helping her residents set aside “impostor syndrome” — the notion that they aren’t suitable for a certain job or leadership role. Women tend to feel they must be perfect to qualify, the theory goes, while many men simply assume themselves to be qualified.

While some aspects of coeducation evolved smoothly, progress was hard-fought in other arenas. In 1981, Notre Dame reached an out-of-court settlement of a class-action federal lawsuit involving more than 60 female faculty members who claimed gender discrimination in hiring and tenure decisions. The agreement established an appeals process for professors who felt they had been unfairly treated.

Some men who initially opposed the idea of a coeducational Notre Dame changed their minds after their daughters — or granddaughters — were admitted and enrolled as students.

“After 10 years, genuine coeducation appears within reach,” Notre Dame Magazine reported in 1982. That year, women composed 28 percent of the freshman class. A decade later, 44 percent of first-year students were female. Today, the undergraduate student body is 48 percent female and 52 percent male, a ratio determined by the University’s residence hall capacities. Balancing the number of men and women has dramatically improved campus life.

Still, women attending at the same time have sometimes had very different experiences based on their field of study, their professors, their extracurricular activities and their friendships.

When Molly Kinder ’01 was chosen to serve as the first female member of the Irish Guard, she was shunned by the nine other guardsmen, and her selection was harshly criticized by some alumni. Standing 6-foot-3, Kinder had met the Guard’s height requirement — since eliminated — and she passed the rigorous tryout.

Her struggles were only beginning. She received negative comments from strangers and read chat room messages and letters to the editor of campus publications claiming that her presence forever marred the Guard’s image. “It exposed that this issue of gender at Notre Dame in the year 2000 was a very touchy subject,” revealing truths the University was still grappling with, she says. “How does Notre Dame change and be inclusive . . . and what does that mean for the men on campus — or the men alums — in terms of how open they were to accepting those changes?”

Kinder has since spoken about her time on the Guard and the institutional challenge — and importance — of evolving cherished traditions. “Otherwise we’re just ossified. We don’t progress,” she says.

Since Kinder, a dozen other women have served on the Irish Guard. Current students find her story bewildering: The Guard has included women since before many of them were born.

Kinder’s contemporary, Brooke Norton Lais ’02, was Notre Dame’s first female student body president. It had taken nearly three decades of coeducation before a woman was elected to the top student government position.

Lais had served as student body vice president as a junior and Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, CSC, University president emeritus, encouraged her to run for the top job. “He said bringing women to Notre Dame was his greatest achievement, but it wouldn’t be totally fulfilled until there was a woman student body president,” she says.

Lais experienced no pushback to breaking a significant gender barrier. “I felt very supported. It was a great place to become a woman leader,” she says.

There’s still room for improvement today. Men and women seem integrated in the classroom, but less so when it comes to social life. The attitude that college fun must intertwine with alcohol persists, which doesn’t necessarily encourage healthy and respectful friendships between women and men. The system of single-sex residence halls prompts perennial student gripes — from a disparity in the enforcement of rules to the effects of segregation by gender. But no plans are afoot for coed dorms.

The faculty needs more women to mirror the growing diversity of the student body and American society. Women are underrepresented on the faculty of some academic departments, particularly in the sciences and engineering. Today’s students notice when a course syllabus draws primarily — or exclusively — on the work of male scholars. The mostly white, mostly male Notre Dame central administration is another topic of discussion. University leaders recognize and are actively working to improve this lack of representative diversity.

Julianne Downing ’22 doesn’t feel she was ever treated as less than a male student in her classes. Still, some memories endure, such as the time a male professor called her writing “sassy” — an adjective that likely wouldn’t be applied to a man. She recalls, on her first day as a student, a professor introducing himself to the class with the claim of being “known as the sexist professor on campus,” He added: “If you’re going to have a problem with that, you should probably leave.” Downing left. “That was the first impression I had of the University,” she says, “which luckily did not come to be characteristic of my experience.”

Downing served as president of FeministND, a student group that educates and advocates for gender equality, consistent with Notre Dame’s mission. The group provides a space — via social media and in-person events — for peers and University employees to join in conversation and advocacy regarding equality of the sexes.

To students of this generation, Downing says, the single-sex residence hall system “is impressively outdated.” Parietals and other rules, she adds, are strictly enforced in women’s dorms but not in many men’s halls.

“I would love to see a woman president of the University,” she says, noting that Fordham University — a Jesuit institution — is inaugurating a woman as president, the first noncleric in the school’s history. Notre Dame’s bylaws stipulate that the University president must be a Holy Cross priest.

Zakiya George ’22 majored in computer science, where most of her instructors and classmates were men. She never felt marginalized in a classroom, she says. “We’re treated as equals. I think my opinion is valued just as much as my male counterparts’ in class.”

George served as president of Shades of Ebony, a student organization formed 20 years ago for women of color to empower themselves and build community. She notes the largely male and white University leadership. “We’re very rarely exposed to people that look like us,” she says. “You just don’t see yourself in those positions, so you internalize the fact that they’re not made for you.”

Still, when these students hear about the rating of women in the dining halls or the disdain Molly Kinder faced, they recognize progress is occurring — albeit more slowly than they would like.

“It’s so easy to feel like your problems are the worst of it,” George says. “And then when you hear stories about other decades and other generations, you’re like: ‘Wow. I’m experiencing nothing comparatively.’”

Margaret Fosmoe is an associate editor of this magazine. Contact her at mfosmoe@nd.edu or @mfosmoe.