University of Notre Dame Archives

University of Notre Dame Archives

- Sisterhood

- Sistering, Sheila Weller

- My Warm Spot, Genevieve Redsten ’22

- Who Do I Say I Am? Maraya Steadman ’89, ’90MBA

- The Ones Who Came Before, Elizabeth Hogan ’99

- A Benevolence of Friends, Mary McGreevy ’89

- Still Some Loose Threads, Maggie Green Cambria ’88

- Flame Launcher, Interview by Tess Gunty ’15

- Rider on the Storm, John Rosengren

- Under the Long Haul, Abby Jorgensen ’16, ’18M.A.

- Writing Her Own Script, Madeline Buckley ’11

- Callings Unanswered, Anna Keating ’06

- Much More than Baby Talk, Adriana Pratt ’12

- Undeterred, Abigail Pesta ’91

- The Good Place, John Nagy ’00M.A.

- Scene Setter, Jason Kelly ’95

- She’s Got Game, Lesley Visser

Notre Dame’s commencement in 1917 bustled with celebration. The year marked the diamond jubilee of Notre Dame’s founding, the long-awaited Lemonnier Library — the building now called Bond Hall — was dedicated, and two new graduates were cheered when their names were announced in Washington Hall. Sister Mary Lucretia Kearns, CSC, ’17M.S., ’23Ph.D. and Sister Mary Francis Jerome O’Laughlin, CSC, ’17M.A. became the first in a very long line of women to earn degrees at Notre Dame before coeducation fully took hold 55 years later in the fall of 1972.

It is unclear when Notre Dame first opened the door to female students, to how many and why. On November 17, 1916, Notre Dame’s president, Rev. John W. Cavanaugh, CSC, wrote to his counterpart at Saint Mary’s College, Mother Pauline O’Neill, CSC, to announce that a Notre Dame faculty committee, “appointed to consider the question of granting the Master’s Degree to Sisters or pupils of Saint Mary’s for post graduate work,” had decided to confer degrees on the following conditions:

1. Candidates must go through the form of matriculation at the University. This will be arranged conveniently whenever requested by you. The registrar will go to St. Mary’s for the purpose, if you so desire.

2. The degrees will be conferred for the same quantity and quality of work as that required of students of the University of Notre Dame.

3. The post graduate work must be done under the direction of [Notre Dame] teachers.

Cavanaugh trusted this was satisfactory to Mother Pauline and thus formally established a path for women to earn degrees at Notre Dame.

The first women recorded in Notre Dame’s student ledgers were six Sisters of the Holy Cross from Saint Mary’s for the 1916-17 academic year. It is likely these women earned their advanced degrees in a similar manner as male students — “under the direction of and by special arrangement with the faculty.”

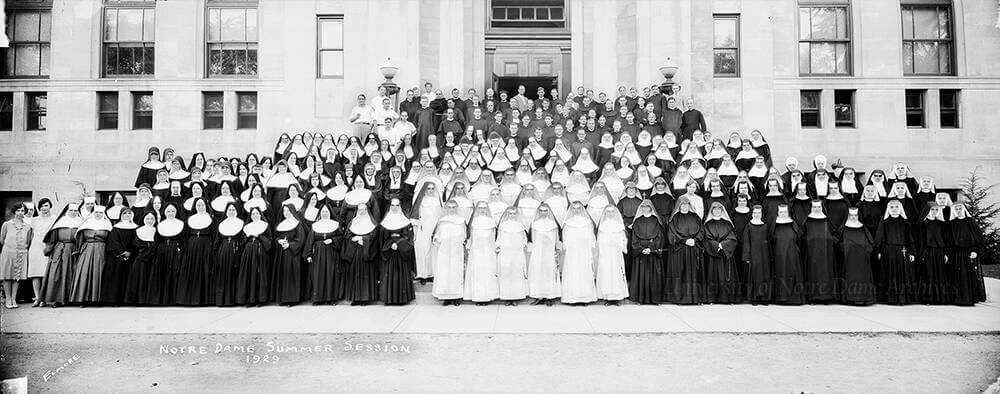

At the behest of Notre Dame’s director of studies, Rev. Matthew Schumacher, CSC, the arrangement between Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s quickly grew. In April 1918, Cavanaugh announced that Notre Dame would open a Summer School to priests, brothers and sisters from all orders, as well as laypeople of both sexes. This announcement met with resounding support from bishops across the country, and enrollment that summer exceeded 200 students.

Summer School instructors were members of the regular Notre Dame faculty, including William Hoynes in law, Francis Kervick in architecture, Rev. Julius Nieuwland, CSC, in science, Knute Rockne in physical education and Rev. John O’Hara, CSC, in history. At the time, male and female students could earn an advanced degree in three summers and an undergraduate degree in four. By 1921, women were also added to the Summer School faculty, although not to the regular faculty.

Rev. James A. Burns, CSC, the first University president with a doctoral degree, took the helm at Notre Dame in 1919. During his three-year tenure, he began molding Notre Dame into a modern institution by strengthening the curriculum and the quality of professors while expanding academic, residential and athletic facilities. The preparatory boarding school for high school students was dissolved in 1922, and the minims — boys under the age of 13 — moved out of St. Edward’s Hall in 1929. As noted in The Notre Dame Scholastic on May 11, 1918, “It is found that the summer sessions attract a more mature, and certainly a very earnest, class of students, drawn largely from the professions, and many of them graduate students. They create a demand for new and advanced courses, which, once begun, tend to become permanently fixed in the curriculum.” As predicted, the Summer School led to the establishment of Notre Dame’s Graduate School, which was coeducational from the outset.

While the Summer School was open to all, the sisters were the stars of the show and became synonymous with the program. Most of these women were teachers or administrators in their religious orders looking to bolster their credentials. A Catholic university like Notre Dame was a natural choice.

As the program grew, the women’s studies seeped into the regular academic year. Clarence Manion, a former dean of the Law School, noted that he remembered Sister Mary Aloysi Kiener, SND, of Cleveland in the history classes he taught during the year while he was a law student in the early 1920s. Kiener was in the first cohort of two lay and three religious women to earn bachelor’s degrees in 1922. Adding a master’s degree in 1923 and a doctorate in 1930, she became Notre Dame’s first female triple Domer.

Overall, between 1917 and August 1971, Notre Dame conferred 342 bachelor’s degrees, 4,128 master’s degrees, 184 doctoral degrees and two law degrees on women.

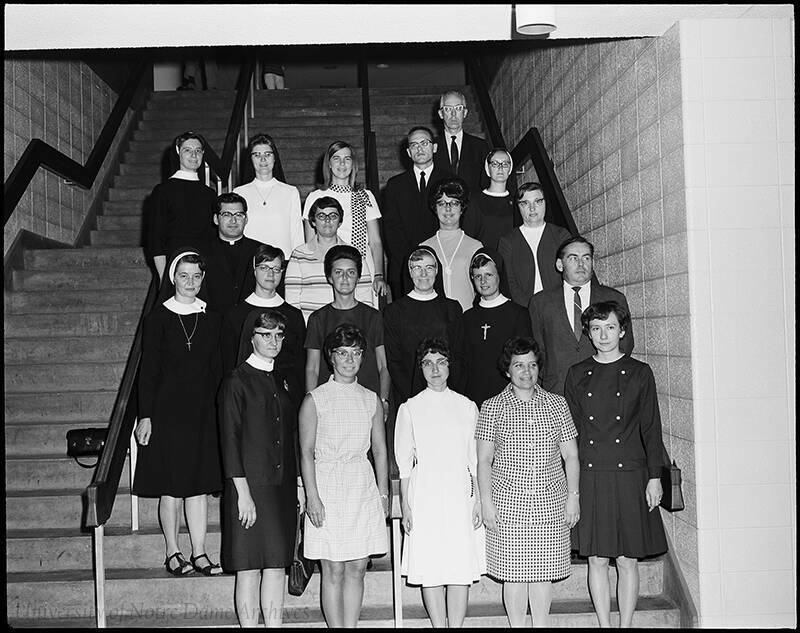

By 1959, some 61 women representing 40 religious communities were working on their degrees throughout the regular academic year. As more women were determined to earn their degrees quicker than the summer session allowed, Notre Dame broke ground on Lewis Hall in 1964 to accommodate about 150 female students. This new residence hall allowed women to earn advanced degrees in 15 consecutive months rather than across five summers. Overall, between 1917 and August 1971, Notre Dame conferred 342 bachelor’s degrees, 4,128 master’s degrees, 184 doctoral degrees and two law degrees on women.

Acknowledgment of these alumnae as members of the Notre Dame family waxed and waned. In 1927, the women formed an Alumnae Association, and over 100 women attended the first meeting to elect officers to it — the Alumni Association’s first affinity group. The Women’s Club, as it was sometimes called, was given space in The Notre Dame Alumnus, a publication of the Alumni Association, and recaps of the summer session appeared in the Scholastic. Many of these women had a strong bond with Notre Dame and were honored to be counted among the alumni.

Occasionally, University publications reminded their readers that, yes, Notre Dame did have female students. In 1955, a story in Notre Dame: A Magazine acknowledged that “the nuns at Notre Dame during the summer school session are as much a part of the University as those husky lads who trod the campus from September to June.” Six years later, the magazine again declared that “the University salutes these ‘Coeds of the Cloth,’ and welcomes them to the Notre Dame family.”

The growing presence of women on campus in the late 1950s and ’60s prompted Ave Maria Press to publish an identification chart of the habits of the orders of sisters, brothers and priests represented among the student body. The brochure challenged readers, who may have had a full inventory of the birds and flowers on campus, to see how many different orders they could identify.

In 1965 Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s established a Co-Exchange Program where students of one institution could take classes at the other, filling Notre Dame’s classrooms with even more women. By the time rumblings of full coeducation — in particular a merger with Saint Mary’s — came about in the late ’60s, the effort spurred a backlash among a small faction of alumni. Notre Dame had been an all-male bastion for over 125 years, they complained. Why change?

Had these men been paying attention, they would have known women had been in the classrooms alongside them for over five decades. Women made up about 10 percent of Notre Dame’s living alumni in 1970, when the Alumni Association published a first-in-a-long-time directory of over 30,000 graduates; however, acknowledgment in campus publications of the sisters with advanced degrees was rare, and the laywomen and undergraduate alumnae were almost never mentioned.

In 1971, Notre Dame’s Board of Trustees announced that, “In the light of the changing role of women today, particular concern must be exercised for the full and equal participation by women in the intellectual and social life of ND.” Women had long been a part of the intellectual life at Notre Dame, but full integration into the social life was yet to be accomplished. The fall of 1972 marked the beginning of true coeducation at Notre Dame, but it is important to continue to salute the thousands of women who preceded those pioneers and to embrace these loyal daughters as members of the Notre Dame family.

Elizabeth Hogan is senior archivist for graphic materials in the University of Notre Dame Archives.