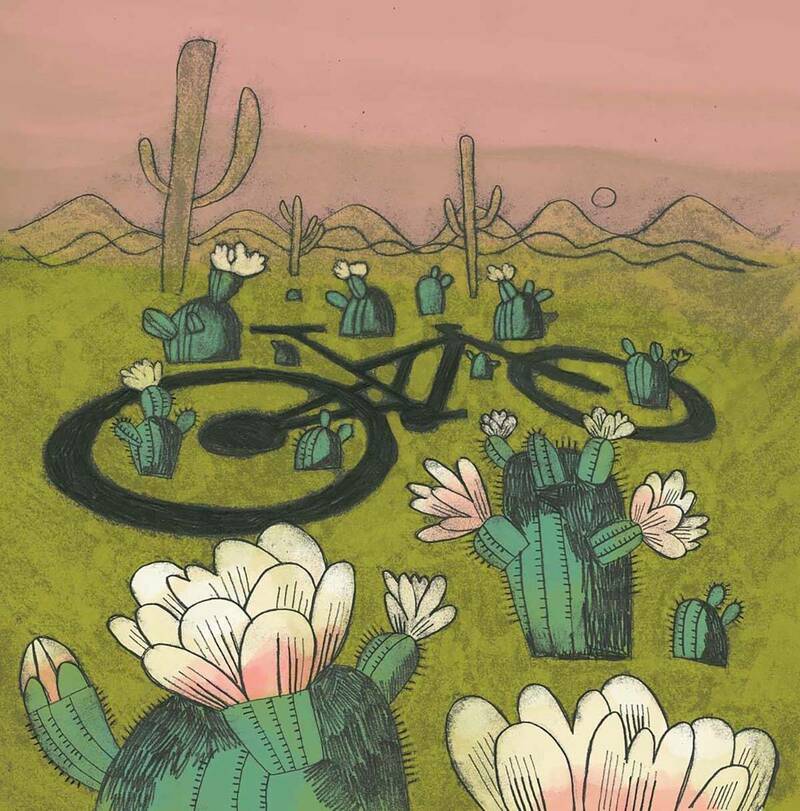

Illustration by Elissa Turnbull

Illustration by Elissa Turnbull

I’m on my knees in the kitchen with a bucket, suds, sponge and rags, cleaning my bike. Running my damp rag over the handlebars, I dig at grit in small crevices where joints meet. Wipe my eyes with the back of my wrist. Give up and let my tears splash on the floor for the dog to lick up. Laugh at how life is just like that.

I remember the first mountain bike race I ever watched. I was 20 years old, camping with a boyfriend. We set up our tents at the base of Mount Humphreys — a quiet slice of woods, until the mountain bikers came zooming past.

Tires kicked up the red Arizona dirt. Spokes whizzed. Gleeful shouts echoed in the timbers. My boyfriend lost interest fast, cracked open a beer and fell asleep in the hammock. But I stood there, a dream kicking up dirt in my mind. I was gonna be one of those bad-ass girls — tearing down the mountain like a grizzly.

When I turned 42, I decided I could do anything. After I trained for an Ironman, I told myself it was time. I fell in love with desert mountain trails — specifically Trail 100, a winding spine of dirt connecting the Phoenix mountains like vertebrae, dipping and climbing through the city.

I got lost for hours out there, exploring alone. Once I popped a tire on cactus needles. Another time, I skidded to a standstill for a trail-crossing tortoise. I think I ran over a rattlesnake on one ride, but I didn’t stop to check.

I fell often, and I fell hard. I kept getting up.

Moving into my 50s, I sponsored the mountain bike club at the high school where I teach, keeping pace with 18-year-old boys. I was convinced I would never stop riding. Always. On trails. Into my 70s. My 80s.

I scrub harder. The derailleur’s grimy. The gears’ peaks and grooves require a toothbrush.

It’s OK, I reassure myself. Wisdom tells me it’s important to feel the disappointment when it comes, because if I don’t, it will take up residence somewhere within me, impatient to be felt. I don’t have room for that.

I whisper to no one in particular, although maybe it’s meant for the bike, “It’s not what I thought it was going to be.”

The air around the bike and me is still, but inside my chest, heat rolls from my heart into my throat. I’m selling the bike.

I keep breathing.

This isn’t my first bike. This one is lightweight and more than we could afford. One day while I was teaching via computer screen in my bedroom, commotion in the living room interrupted a stressful class. I came out to find a giant box leaned against the wall, my husband’s messy handwriting scribbled on a sticky note. “For Mommo.”

He’s a man who doesn’t need all the words I do.

I ripped into the cardboard. The bike was slick, a pretty, muted turquoise. I wanted to take it out to the trails right away so I’d be seen. Canyon bikes were the latest craze. It would be butter on warm toast, handling itself. Grown men would be jealous of me.

“I got one too,” my husband beamed. The rest of the world fell away.

Together, with our shiny, new full-suspension bikes, we rode nearly every night for a year in the dark. Warm wind cooled our damp skin. With cactus shadows floating past, reality shifted, and an hour and a half crossed into eternity.

Some lucky person will buy my bike, but they won’t get my memories: creamy coral sunsets at the summit of a trail, pink dust settling as I hold my breath because the moment is so damn precious with the bike resting beneath me.

Then tearing down the winding trail to make it back for dinner. No one tells you that biking is the closest thing to flying, but it is.

I haven’t ridden for a year now, and I haven’t worried about it too much — life handed me a small heart attack, a pacemaker and a diagnosis of heart failure, which I really don’t believe and never will. I don’t obsess about it — instead I get to feel the new ways to experience the love of my husband and the strength of my will. Trail 100 is just as brilliant when you’re walking.

One last time, I run my fingertips over chips in the paint and vow to keep healing my own. I put my palms on my chest. Feel the sturdy little pacemaker doing its job.

It’s going to be OK.

Thank you, body, for being tough. I don’t know another woman who can fall as much and keep getting up. Just as bad ass as I once dreamed.

What I’m most grateful for is the gift, the surprise from my husband, so we wouldn’t go crazy in the house with our three teenagers during lockdown.

I toss my rag into the bucket. Tell myself it’s OK to grieve for the quad-crushing hills I won’t climb. For the daring descents I’ll miss. For the lovely season of life that was desert night rides.

Feeling lighter, I dump the bucket and wheel the bike out to the garage. I might not be at the top of a mountain, but heaven can still touch me — this time on the kitchen floor.

Kerith Mickelson lives in Phoenix with her husband, three kids and pets. When she’s not teaching English at her old high school, she’s leading classes in yoga and tai chi. Her next goal is to relearn how to skateboard — not tricks, but for balance.