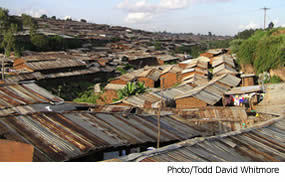

From the second floor of the Holy Cross congregation’s McCauley Formation House in Nairobi, Kenya, visitors have an unobstructed view down into what appears to be a vast and impossibly crowded rail yard. Weather-beaten boxcars extend to the horizon in three directions.

Except they aren’t boxcars.

The grim reality is visible only at ground level. The “boxcars” are actually rectangular shacks, their walls made of dried red-orange mud squished into a latticework of bamboo sticks. Some of the shacks have heavy rocks on their roofs, which keep the corrugated metal from blowing off. Crooked paths of red clay run between the fragile structures. The rutted surfaces are feathered everywhere with embedded scraps of plastic bags. Planks lie across rivulets carrying human and other waste down the hillside.

Welcome to Kibera, an obscenely photogenic warren of wretched poverty where an estimated 1 million people live. Kenya’s capital has more than 130 such slums or “informal settlements” housing more than half the city’s population on less than 2 percent of its land. Kibera is the largest such slum in Nairobi and, by some estimates, the world.

Conditions here are what international aid agencies term “extreme poverty,” people living on less than a dollar a day. In this case, a lot less. First-time visitors from developed countries—like the author of this article, part of a group of mostly faculty from Notre Dame and two other Holy Cross universities that toured the Holy Cross Missions in East Africa earlier this year—can hardly believe their eyes or imagine a more deprived existence. But something about the place doesn’t add up.

As we walk between rows of shacks on a sunny June afternoon, the slum dwellers in general appear clean and neatly dressed and even look contented. A herd of grinning dark-skinned boys begins to tag along behind the line of visibly shaken wazungu (Swahili for “white people”). “How are you?” one chirps, and then another and another until they are chanting it in unison like a cheer: “Howareyou. Howareyou. Howareyou. Howareyou.”

“Fine, how are you?” I respond to silenced faces that have run out of English.

Only later does it occur to me that the more accurate answer would have been, "Very confused.

***

After nearly two weeks in Kenya and Uganda visiting Holy Cross-assisted churches, schools, health clinics, family and youth centers, and formation houses (where young Africans starting on the road to becoming CSC priests, brothers or sisters live), we’ve grown accustomed to the warmth of the East Africans, their impeccable manners, the perpetual greeting of “You are most welcome.” But this is too much. Don’t these people know how to register misery?

We know better than to expect a simple explanation from the leader of our expedition, Father Paul Kollman, CSC, ‘84, ’90M.Div. The youthful 42-year-old Notre Dame assistant professor of theology has studied, taught and served in pastoral capacities in Uganda, Kenya and also in Tanzania, the third country that surrounds Lake Victoria, the world’s second-largest freshwater lake. He’s also written a history of origins of the Catholic Church in East Africa. The book is due out this fall. Almost always when we ask about Africa’s enduring conflicts and contradictions, Father Paul begins with a knowing and judicious, “It’s complicated.”

He’s not one to exaggerate.

One clue to the dearth of distress among the people is their heartfelt religious devotion. More than two-thirds of the populations of both Kenya and Uganda are classified as Christians. That includes mushrooming Pentecostal churches and similar charismatic movements within other denominations, including Catholicism. After Christianity comes Islam (16 percent and also growing), the remnants of indigenous beliefs and hybrids of various traditions. In Uganda, Catholics make up 45 percent of the population—10.4 million people—which, according to a report in the National Catholic Reporter, makes it the fourth-largest Catholic country where English is the dominant language. (The top three, in order, are India, the United States and Canada.)

The Church’s outsized influence is especially evident during our visit. The morning after our descent into Kibera, Father Tom Smith, CSC, ‘67, ’70M.A., director of Holy Cross Missions, celebrates Mass in the McCauley Formation House chapel. Smith has worked out of an office in Moreau Seminary at Notre Dame since 2001 but spent 23 of the last 35 years in East Africa. During Idi Amin’s reign of terror in the 1970s he smuggled Africans through military checkpoints hidden under blankets in his car.

In his homily he mentions that he learned all about the saints while growing up but says they have never been present for him in the way the Ugandan Martyrs are present in the lives of East Africans. He’s talking about some of the first natives of the East African interior to convert to Christianity after the arrival of a wave of Anglican and then Catholic missionaries in the 1870s.

When the Anglicans and Catholics came to Buganda, the largest kingdom in what would become Uganda, the local king gave them a warm reception. Many converts even became pages in the royal court. But the next king didn’t like his authority being relegated to second place behind a deity. He eventually began executing converts. A total of 45 Christians were made examples of in a variety of grisly ways, including decapitation and ravaging by wild dogs. On one particular day, June 3, 1886, 22 were burned alive in the village of Namugongo, east of the present-day Ugandan capital, Kampala.

June 3 is now a national holiday in Uganda, Uganda Martyrs Day. And that’s the occasion for Father Tom’s homily. The priest imagines the tens of thousands of pilgrims who will be in Namugongo today at the Catholic martyrs shrine. Some will have walked hundreds of miles to get there. It’s that sort of organic devotion, he says, that the Church has tried to tap into in Africa. And has tapped into successfully.

To the first-time visitor to Africa, Catholicism East African-style seems like a familiar piece of furniture upholstered in a different pattern and color. In every church or chapel our group visited, the tabernacle was a miniature banda, the traditional round African hut with a thatched roof. A mural dominating the sanctuary of the Holy Cross Catholic Church in Dandora—a poor, but not as poor as Kibera, neighborhood in eastern Nairobi—depicts the holy family as black Africans. Even a dark-skin hand reaches down from heaven.

On the second Sunday of our excursion we join the Christians of Kyarusozi, a rural parish in hilly western Uganda, for Mass in a simple meeting hall labeled Saint Joseph’s Church of Kyembogo. The place is packed, and we’re escorted to seats of honor on a platform flanking the altar. The liturgy is spoken entirely in the local language of the district, Rutoro, but we can easily pick out gestures common to any Mass.

The front rank of the church choir thumps drums and rattles small box-shaped percussion instruments filled with beans. Young women wearing hula-skirt-like decorations over their brightly colored clothing saunter down the aisle and then shake their hips energetically. Behind them other dancers wearing maraca-like balls, called orunyege, on their ankles stomp and rattle in time with the music.

After Mass I ask the white-haired celebrant, Father Richard Potthast, CSC, ’63, if this exuberant singing and dancing is regulation, liturgically speaking. The South Bend native, who has served in the parish since 1966, looks at me impatiently.

“Have you ever read the Psalms?” he asks. I sheepishly realize he’s talking about the psalmist’s exhortation to praise God with singing and dancing.

Kyarusozi Parish is about 50 miles northeast of the Ugandan town of Fort Portal, the original location of Holy Cross missionaries in Africa. Three newly ordained priests arrived there in 1958. They’d originally prepared to go to the order’s mission in Bengal (of Bengal Bouts fame) India, now part of Bangladesh. Their luggage had already been shipped there. But at the last minute they were redirected to Uganda. One of the three, Father Robert Hesse, CSC, who turns 79 in December, still lives in Uganda. Though technically retired, he continues to assist in pastoral work in the parish of Bugembe near the small city of Jinja in eastern Uganda.

In his history of Holy Cross in East Africa, Father William Blum, CSC, ’60, writes that the Holy See and early Catholic missionaries to Africa wanted to make sure the Church was on a solid footing when African countries gained independence from European colonial powers in the early 1960s. Missionary groups not already in Africa were encouraged to come help. Enter Holy Cross.

For the next 20-some years, that’s mainly what the CSCs did—help build up the local Church. It wasn’t until 1980 that the order began accepting Africans as candidates for religious formation. Today, 23 East Africans have become CSC priests and brothers. The area also has produced eight Sisters of the Holy Cross; three more are in Ghana in West Africa.

In addition to Kyarosozi in western Uganda and Bugembe in the east, the order is responsible for parishes in Nairobi (Dandora) and its most recently acquired outpost, Saint Brendan’s Parish in Kitete in north-central Tanzania, added in 2000. Holy Cross members also continue to assist with various Church activities in Fort Portal.

In each location the CSCs have helped found and operate churches, medical facilities, schools and even colleges that educate seminarians of their own and those in formation for other religious orders. School officials proudly show off their new computer labs and libraries and recite statistics on test scores and growing enrollments. Father Potthast tells us that seven years ago the Catholic high school in Kyembogo had five students; now the enrollment surpasses 300.

The visitor comes away with the impression that things are not so bad here in this corner of the Third World. The Church is making a difference, a big difference. Not every problem has been solved, for sure, but with special offerings from well-heeled parishes back home, platoons more missionaries, an injection of management skill. . . .

And then you climb down into Kibera, see the sewerless and malnourished multitudes, and the scale of the problem seems monumental.

If only it were that small.

***

Africa is the poorest continent on Earth. Of the 700 million people living in the sub-Saharan part, nearly half—a number greater than the entire population of the United States—subsist on 65 cents or less a day.

It’s also the only continent to have grown poorer in the last 20 years. According to a United Nations report, the percentage of people living on less than a dollar a day dropped worldwide from 40 percent to 20 percent between 1980 and 2003. But in Africa it actually edged up, from 45 to 46 percent. To put in perspective how bad off Africa is, in the second-poorest area of the globe, South Asia, the poverty rate is 17 percentage points lower.

How the continent came to be such a basket case is a long story, and, as Father Paul would say, “It’s complicated.”

Those familiar with physiologist Jared Diamond’s book Guns, Germs and Steel and the PBS series based on it that aired earlier this year know his theory that European societies advanced faster than those elsewhere because of an early advantage they enjoyed at the dawn of man’s switch from hunter/gatherer to farmer. Namely, the Europeans had native species of animals that could be domesticated. Goats and sheep could feed off the stubble from harvested fields and later be eaten to provide high-protein food or shorn or skinned to provide clothing. Larger animals like horses and cattle could be harnessed to do the grunt work of farming.

Diamond speculates that draft animals increased crop productivity so much that it freed individuals to develop new technologies. That led to the production of weaponry, which gave European explorers and fortune-seekers the firepower to conquer and exploit.

As was the case almost everywhere else in the world, Africa was saddled with native animal species such as zebra and rhinoceros that proved impossible to domesticate. Without animal help, the theory goes, the Africans had to work all day just to feed themselves.

Many still do. Uganda is lucky compared with such famine-prone African countries as Ethiopia. What it lacks in easily exportable energy resources like coal or oil, it makes up for in fertile soils. The country’s lush, green countryside led Winston Churchill to dub it the Pearl of Africa. So even during violent conflicts and disease pandemics, Kollman says, Uganda’s rural poor can usually grow enough to survive.

In Bugembe Parish, 55-year-old Godfrey Waswa, his wife, Alice Apolote, and 10 children subsist on corn, avocados and papaya they cultivate on a small plot of land surrounding their mud hut. It’s a labor-intensive existence and not helped by the fact that they, like most rural poor, have no running water. They have to buy it from a neighbor with a standpipe or from a business in town and then lug home however much they need that day in a jerry can.

Many of Africa’s rural poor flock to the city in search of a better life, but few find it. A short story published in The New Yorker earlier this year by a Jesuit priest from Nigeria, Uwem Akpan, describes the day-to-day existence of an imaginary family evicted from Kibera for failing to pay their rent. Rooms sans electricity and flooring rent for as little as $5 a month in Kibera, so you have to be awfully poor not to keep up.

In the story the family is now living in a shack with a tarp for a roof at the end of an alley. Their main source of income is the wages of their daughter, a street prostitute at 12. In lieu of food, the mother spoons out shoe glue into a plastic bottle for her younger children to sniff. The fumes anesthetize their hunger pangs.

In both Kenya and Uganda, more than three-fourths of people work in agriculture because they don’t have much choice. Crisscrossing the lush countryside of Uganda in a mini-bus, our group sees but one structure that resembles a factory: a Coca-Cola bottling plant. Coke is said to be the largest private employer in Africa.

What most countries in sub-Saharan Africa desperately desire is foreign investment, and they wouldn’t be especially picky. An athletic shoe factory paying what we would consider “slave” wages of $2 a day would still be double the earnings of the average African worker. So why don’t foreign manufacturers swoop in and exploit this desperate labor pool?

One reason is competition. As cheap as labor is in Africa, there are places where people will work for just as little and factories already exist. Says Father Paul Kollman, “The Chinese can export anything cheaper to here than the Ugandans can make it.”

Father David Kashangaki, CSC, ‘05M.A., assistant director of the CSC’s Saint Andre Formation House in Bugembe, says the Ugandan government is trying to entice foreign investment, “but until they solve the basic issues, it’s hard to get companies to come in.”

He means infrastructure. Roads, reliable electrical service, medical care—all are lacking in East Africa. For instance, Uganda, which is slightly smaller than Oregon, has about 17,000 miles of roads, but less than 7 percent are paved. And many are crumbling. A country with more than 26 million people has only one CAT scanner, says Makerere University Chaplain Father Lawrence Kanyike, CSC, ’78Ph.D., who was in need of one after suffering a stroke a few years ago.

Another major deterrent to foreign investors has been government instability. When European colonists arrived in the 19th century, the African continent consisted of several thousand kingdoms and chieftaincies. As a special report in The Economist magazine put it, by the time the colonial powers left in the mid-20th century, they had “squeezed the whole lot into a few dozen nation states whose borders cut some tribes in half and lumped others together with neighbors they did not much like.” The resulting countries were rife with ethnic tensions, which often led to civil wars. Also, Africans were hardly prepared for the kind of parliamentary democracy bequeathed to them by the Europeans. A bureaucracy needs educated people to function. But as The Economist report notes, when Tanzania gained independence from Great Britain in 1961, its population included a grand total of 16 university graduates. (Ironically, Tanzania has turned out to be one of Africa’s most stable countries.)

The result has been a long series of brutal dictatorships punctuated by bloody coups and revolutions. From the early 1960s to the late 1980s the continent saw more than 70 coups and 13 presidential assassinations. The joke in Africa is that each country gets one free election—the first one following independence. After that, you get an army together.

Some such transitions take longer than others. The present leader of Uganda, Yoweri Museveni, led a rebellion that in 1985 toppled the brutal dictator Milton Obote, successor to Idi Amin. Museveni generally receives high marks for restoring stability to the country. But nearly 20 years after he came to power, government forces still don’t control every square mile of Uganda. An armed rebellion now led by a madman (see The Army of Kidnapped Children) continues to churn in the northern part of the country.

That rebellion by the Lord’s Resistance Army has resulted in more than a million people being displaced from their homes. These people are categorized as Internally Displaced People or IDPs. Uganda is also the temporary (maybe) home to 150,000 refugees from conflicts in other countries, including neighboring Sudan. None of this makes Uganda special. Africa is the refugee capital of the world, hosting 30 percent of all refugees and 50 percent of the world’s IDPs.

In 1999 the Law School of Makerere University founded the Refugee Law Project to protect and promote the rights of refugees in Uganda. Peter Ekayu, a lawyer with the organization, describes the tribulations of one client, a Rwandan:

The man’s father, a Hutu, was a top official in government during the 1994 genocide committed by Hutus against the Tutsis. More than a half-million people, 8 percent of Rwanda’s population, were slaughtered in just three months. The man’s mother was Tutsi. The Tutsis eventually killed the man’s father, and then the Hutus wanted to kill his mother in revenge. The son fled with his mother and four siblings to the Democratic Republic of Congo. After the situation stabilized in his home country they returned, only to find the family home occupied, so they went to a second home. That home was set ablaze and everyone in it burned to death except Ekayu’s client.

Several years, relocations, misunderstandings and narrow escapes later, the man lives in fear for his life in Kampala. The Refugee Law Project is continuing to advocate for his permanent resettlement, Ekayu says.

The lack of peaceful transfers of power isn’t the only reason repressive governments have dominated Africa so long. During the Cold War the United States and Soviet Union, both seeking strategic advantage, showered money on various African countries. They didn’t seem to care how the money was spent. Aid dispensed in the form of loans often ended up in Swiss bank accounts of brutal dictators. By one published estimate, for every $1 lent to Africa between 1970 and 1996, 80 cents flowed out of the country.

Years later the embezzling dictators may be gone, but their debts have been inherited by current governments. Even relaxed repayment schedules are bleeding developing countries out of revenues desperately needed to educate people and improve infrastructure. Some organizations promoting debt forgiveness for African countries, like the American Friends Service Committee, say it’s a matter of simple justice. “According to international law,” states one of the Quaker group’s publications, “people should not be forced to pay debts that did not benefit them and that were contracted and used to suppress, jail and kill them.”

Another enduring roadblock to African development has been disease. Malaria alone kills more than a million African children a year.

Then there’s AIDS. Ten percent of the world’s population lives in Africa, but the continent is home to two-thirds of the 38 million people infected with HIV/AIDS. In some places a third of African adults are HIV-positive.

One reason AIDS has spread so fast is poverty. People who can’t afford antibiotics to treat other sexually transmitted diseases end up with open sores, which provide freeways for transmission of the virus. Soldiers and migrant workers help expand the reach of the disease, especially men having sex with prostitutes while away from home. More than 85 percent of Nairobi’s sex workers are thought to be HIV-positive. When the men return home, they’re likely to infect their wives because African women generally don’t feel they have the right to refuse to have sex with their husbands or force them to wear condoms. In some parts of Africa, widows are even expected to undergo a purification rite that involves sleeping with their late husband’s nearest male relative, who may himself be infected.

When both parents in a poor family succumb to AIDS, their children typically end up with grandparents or other relatives who may themselves already be destitute.

Uganda has been held up as a model success story in the battle against AIDS. Through aggressive educational programs promoting abstinence, fidelity and use of condoms, the country’s infection rate has fallen to 5 percent, the government says. But the progress may be exaggerated. At Fort Portal’s Catholic Virika Hospital, where patients are charged $1 a day for medical care, a nurse tells us that on a typical day if 15 patients come in, 10 will turn out to be HIV-positive.

“Through the naked eye,” says the hospital’s CEO, Father Paschal Kabura, “I don’t see [the infection rate] going down.”

Africa once seemed doomed to annihilation by AIDS because people couldn’t afford the anti-retroviral drugs to control the disease. Drug prices have reportedly declined by 95 percent. Nevertheless, it’s estimated that only one HIV-positive African in 400 receives the medication. One reason: Empty stomachs can’t absorb the toxicity of the anti-retroviral drugs. People suffering from lack of food either vomit up the medicine or won’t take it because they know the effect it will have, says Margaret Ogola, a pediatrician who heads the Kenyan bishops’ Commission for Health and Family Life.

Whether it’s because of AIDS, malnutrition or other maladies, dying young is nothing special in sub-Saharan Africa. The infant mortality rate in Uganda is 88 per 1,000 live births, nearly 12 times that of the United States. Due in large part to AIDS, average life expectancy has fallen to 47 in Kenya and less than 45 in Uganda. In the United States it’s above 77.

On average, Ugandan families have seven children. Parents know they’ll need children to take care of them when (if) they grow old. But they also know they’re likely to lose two or three children along the way. So they procreate accordingly.

Ed Cohen is an associate editor of this magazine.