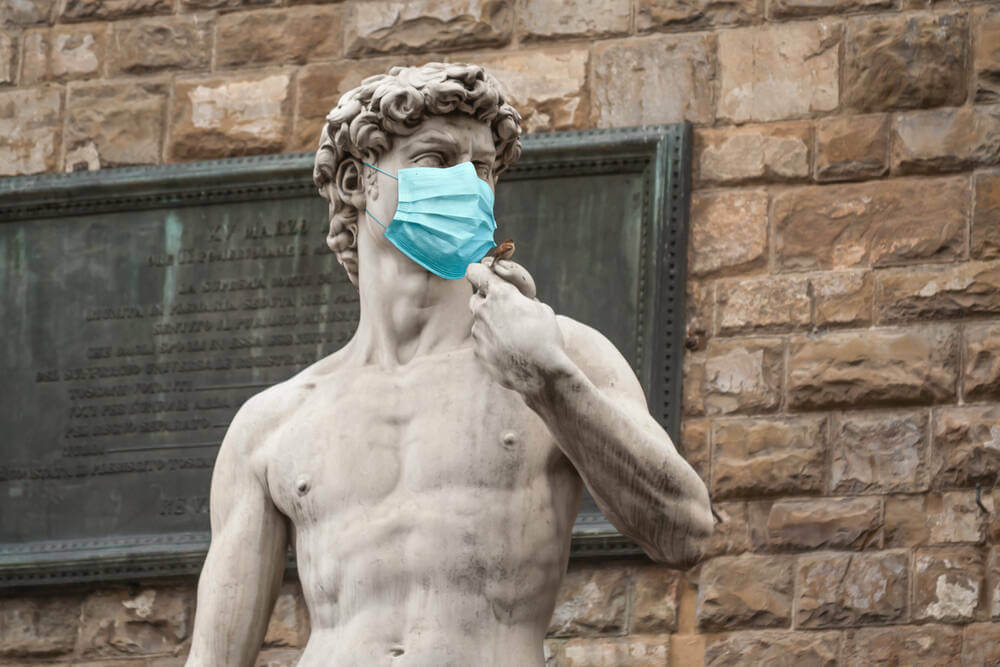

Neither Macron nor LePen inspired enthusiam from the French people. Shutterstock

Neither Macron nor LePen inspired enthusiam from the French people. Shutterstock

The massive sign on the side of the museum at the French port of Marseille declares: “L’épidémie n’est pas finie!” — The epidemic is not finished.

Despite this stark warning, nearly two weeks in Europe on a trip offered by the Notre Dame Alumni Association’s Travel Program demonstrated that several countries are working overtime to return to a state resembling normalcy after two years of COVID-19’s deadly disruptions and their related economic woes.

From Spain to Italy — even with general mask wearing, the showing of vaccine cards, and periodic testing — tourists are starting to descend on Barcelona, Monte Carlo, Rome and other eye-opening precincts in nearly elbow-to-elbow droves. At the Vatican Museum, two days after Easter, several thousand people from all points on a compass willingly flashed vaccine documents to monitors who also made sure the visitors sported KN95 masks for entry. Nobody within earshot complained en route to the immense art collection and the wonders of the Sistine Chapel.

Spain, Italy and the Vatican seemed most vigilant in reminding everyone to keep noses and mouths covered. That, however, didn’t appear to be the case in France, where polarization of the left and right (similar to America) animates domestic politics and day-to-day life. Particularly with a presidential election in full swing, the French temperament was fairly easy to read.

The newspaper Le Monde (in its English edition) summed up the mood going into the second and final round of voting on April 24 with this headline: “Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen beset by the same affliction: rejection.”

A Marseille taxi driver captured the French frame of mind, not all that dissimilar to the view of many American voters during recent presidential contests, with this blunt assessment: “I don’t like either Macron or Le Pen.” (In Marseille, Nice and other French cities on the itinerary, campaign posters were few and difficult to locate.)

Although Macron, the incumbent, ended up winning a second five-year term 58.5 percent to Le Pen’s 41.5 percent, his margin of victory wasn’t nearly as decisive as it was in 2017, when he overwhelmed Le Pen by 66.1 percent to 33.9 percent. About 28 percent of the French electorate “abstained” from voting, the highest amount in half a century and numerical proof of the judgment in Le Monde that citizens going — or not going — to the polls were “demotivated and angry.”

The island of Corsica, a part of France since 1768 — the year before Napoleon Bonaparte was born there — has been roiled of late by a separatist movement seeking independence from the nation a little more than 100 miles to its north. That spirit of independence was on rather conspicuous display Easter Sunday at a high Mass conducted at the Cathédrale Santa Maria Assunta (the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Assumption) in the Corsican capital of Ajaccio. It’s the church where Napoleon was baptized.

Not more than a quarter of the standing-room-only faithful were wearing masks, with a considerably larger number clad in blue jeans. So much for the finery of an Easter parade. At communion time, a young boy of about 10 rode up the center aisle on his foot-propelled scooter, followed shortly thereafter by a senior woman with her little dog in tow. Independence, indeed.

A highlight near the end of the tour was a visit to the U.S. Embassy to the Holy See in Rome and an enlightening session for over an hour with Ambassador Joe Donnelly ’77, ’81J.D. The former senator from Indiana, who presented his ambassadorial credentials and a letter from President Joe Biden to Pope Francis on April 11, reported that the Vatican is doing everything possible to try to bring peace to war-ravaged Ukraine, but Russian President Vladimir Putin thus far seems reluctant to heed any entreaties for stopping the carnage.

Interestingly, Donnelly remarked that he’s met with officials from Ukraine who were in Italy to visit Vatican hierarchy for their diplomatic help. They also met with the U.S. ambassador, he said, to explain the value of American assistance to continue their fight for freedom and sovereignty.

During his time overseas, Donnelly has found that the U.S. is widely admired and looked to for leadership in solving world problems. To him, there’s an encouraging unity of perspective among the diplomatic corps in Rome and the everyday people he’s encountered.

When the COVID-19 pandemic might truly be “finie” and allow unfettered maneuverability abroad is, of course, anyone’s guess. But the consensus of the Notre Dame travelers in our congenial group — the first multi-country journey under the auspices of the Alumni Association since March of 2020 — was uniformly positive.

Despite the current realities of health-related etiquette, this European experience opened several doors to delayed adventures, complete with their own enduring rewards.

Bob Schmuhl is the Walter H. Annenberg-Edmund P. Joyce Professor Emeritus of American studies and journalism at Notre Dame. He’s the author or editor of 15 books, including Fifty Years with Father Hesburgh: On and Off the Record. The expanded edition of his book, The Glory and the Burden: The American Presidency from the New Deal to the Present, will be published this fall by Notre Dame Press.