Andrew McShane rounded the corner in front of the altar of the Basilica of the Sacred Heart and sized up the cacophony in the choir loft: Drills wheezing. Socket wrenches clicking. Wisecracks flying. Workmen calling down from vanishing tiers of organ pipes that still rose three and four stories above the church floor.

Every few minutes a flurry of chords or a quick scale would overwhelm this steady hum of percussive activity, but it sure wasn’t the music that McShane, as organist and director of the Notre Dame Liturgical Choir, was accustomed to hearing echo through the nave during an afternoon rehearsal. It was instead the music of urgent work on a tight deadline searching for a tempo and a rhythm.

The hammering sound on this dreary Tuesday after Christmas was the crank of a manual fork lift lowering long, heavy wooden boxes full of pipes down from the loft rail. The lift tottered under the weight of each descending load. Five hours into the task of removing the Holtkamp Organ’s 2,929 pipes, wrapping them in thick brown paper, crating them and stacking the boxes in the back of the yellow Penske truck parked outside the basilica’s open front doors, the lowest pipes that had filled a picture-window-like box in the organ’s lower case were already packed up and gone.

McShane ’93M.M. stopped on the altar steps to watch the work with a couple of visitors. He shot one of them a sidelong glance, wondering aloud, “You think we’re doing the right thing?”

There could be no answer to that scrap of gallows humor but a grin. The demolition of the Holtkamp in the last dark days of 2015 would leave a scar on the basilica’s south wall that greeted students and massgoers when the church reopened in mid-January. Healing will require a full year, when the new Murdy Family Organ is ready to take its place.

Preparation for the demolition had begun at 6 that Monday morning, when the warm lights emanating from inside the closed church and the giant, festive wreath still hanging above its arched entrance fooled a few curious visitors into thinking a Mass might be underway.

Instead, they found men in yellow reflective vests setting up outdoor workbenches and low construction walls under a gathering ice storm, while a more fortunate group of workers unbolted pews from the church floor and covered the tiles with protective layers of Visqueen, Styrofoam and plywood.

The winter storm was strong enough along the Indiana Toll Road that afternoon to prevent the AB Pipe Organ Service from traveling to campus from the Chicago suburbs to begin the removal.

By 1 o’clock, however, the local crew from Ziolkowski Construction, which works on projects across campus from the stadium to the new dorms, had prepared the worksite for the organ company’s arrival first thing Tuesday morning. They stacked several rows of pews on top of others perpendicular to the basilica’s central aisle and sheltered the baptismal font in a sturdy cubic plywood cocoon.

AB Pipe Organ is building a large, complex electric-action organ for a new church under construction for St. Pius X parish in Granger, Indiana. The company’s owner, Aaron Bogue, said it will combine the parish’s current organ with a new instrument fashioned using both the Holtkamp pipes and several rows of new pipes.

Bogue estimated that the Holtkamp pipes would cost between $300,000 and $400,000 to make new. Notre Dame is donating them to St. Pius, which is paying the cost of the pipe removal and demolition.

Organ pipes are easy to lift out of their toeboards — in the sense that there’s nothing to unbolt or unscrew — but that doesn’t mean the work is simple. Bogue and one of his associates, Chuck Freiberger, a former organ builder and retired elementary school principal, often paused from the work of wrapping and crating to play the next set of pipes and record its wind pressure. Each row was catalogued and boxed before being lowered from the loft.

“The pipes blow at a certain pressure,” Freiberger explained. “And so when you’re revoicing them, when you’re redoing them, it’s nice to know what pressure they were at, because if you go too high, they overblow,” he said, making an unpleasant eee! sound to demonstrate.

“And if you go too low,” he continued, “they won’t speak properly. So you want to start at least at the pressure the organ was originally set at.”

Craig Derry, one of Bogue’s high school classmates, and Kevin Stawiarski, a retired Chicago firefighter and Bogue’s uncle, raced up and down ladders all afternoon, sending buckets of smaller pipes down to Bogue and Freiberger in the loft. They made most of this work at dizzying heights appear effortless. But the tallest front pipes — some 32 feet tall and weighing up to 200 pounds — were a different story. Those waited to come down until day two of the removal.

Meanwhile, two rows of rectangular wooden pipes behind the organ’s concealed upper walkboards could not be touched until the Ziolkowski crew tore away the organ’s case and frame, piece by piece.

The week after New Year’s Day, the entire organ was gone — as was most of the flooring that had supported it. Ziolkowski reinforced the loft and its supporting columns with new steel. Subterranean work to support the Murdy, which will arrive in August, is estimated to be as much as nine and half tons heavier than the Holtkamp, began during fall break last October. Workers pumped eight cubic yards of concrete through an access hole outside the church into new steel-ribbed piers beneath the 145-year-old building, said project manager Anthony Polotto of the university architect’s office.

Paul Fritts, the master organbuilder whose Tacoma, Washington, workshop is creating the Murdy Organ, visited January 15 to take final laser measurements of the loft in preparation for the delivery, assembly, tuning and voicing that will take place during the last five months of this year.

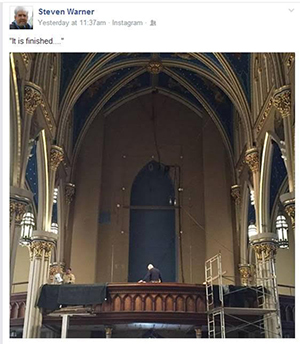

In the meantime, Steve Warner ’80M.A., director of the Notre Dame Folk Choir, had posted a photograph of the basilica’s now-vacant south wall on Instagram. The photo revealed an alcove no more than two feet deep beneath a high Gothic arch, framed by the series of wire and light bulbs that had illuminated countless trips inside the organ case for tuning, maintenance and repairs. Quoting the Gospel of John for Good Friday, Warner wrote, “It is finished.”

Nevertheless, the basilica reopened for Masses on January 17, the first Sunday of the spring semester. Supported by a smaller Fritts organ, the basilica’s six choirs will sing from the west transept throughout 2016.