This wasn’t supposed to be happening. Not again. Not with this group.

Fresh off a momentous victory over North Carolina in the Atlantic Coast Conference championship game, Mike Brey’s Notre Dame team seemed poised to break through in the NCAA Tournament after a decade of disappointments. The Fighting Irish entered the first round in Pittsburgh seeded third in the 2015 tournament’s Midwest region and favored by 12 points over Northeastern. Yet at halftime the Irish clung to a four-point lead, and the ghosts of Marches past seemed to be circling PPG Paints Arena.

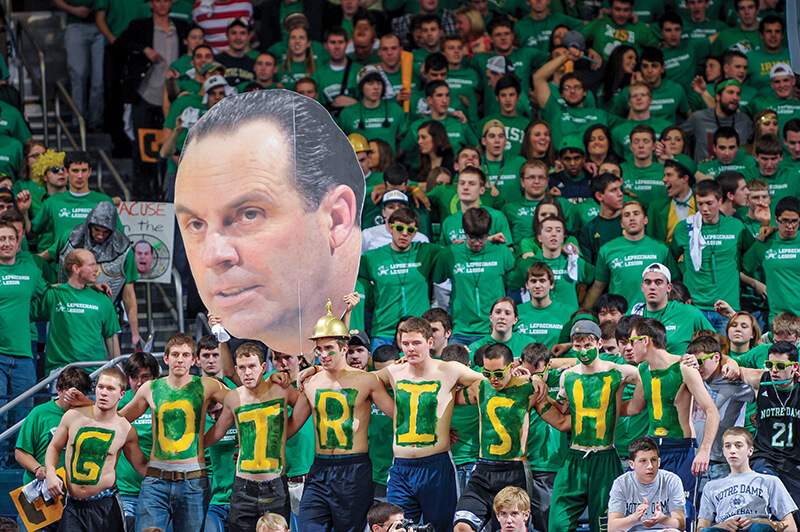

Photos by Matt Cashore ’94

Photos by Matt Cashore ’94

Jack Swarbrick ’76, Notre Dame’s director of athletics, pulled his coach aside. “You need to be Five Overtime Mike,” he told Brey.

Swarbrick was referring to one of the most unusual games in program history. On February 9, 2013, Notre Dame defeated Louisville 104-101 after 26 lead changes and five overtimes. One of the lasting memories of that night at Purcell Pavilion was the contrast in coaches: Rick Pitino on one side, increasingly agitated as the game wore on, and Brey on the other, looking like he’d never had so much fun.

“The difference was, Coach Brey was enjoying it,” remembers Pat Connaughton ’15, then a sophomore, who had 16 points and 14 rebounds in an astounding 56 minutes. “His energy was excitement. Happy to be able to continue to compete.”

Two years later, Swarbrick’s words resonated with Brey as his team returned to the floor in Pittsburgh. He came out consciously more relaxed in the second half and transferred that calm to his players. The Irish survived the gritty challenge from the Huskies and went on to beat Butler and Wichita State en route to the program’s first Elite Eight matchup since 1979.

“That was the best advice an AD has ever given me,” Brey says. “I would say probably from that advice on I’ve maybe had a little bit different perspective.”

That’s meant unleashing Five Overtime Mike at all times. It has meant becoming the self-proclaimed “Loosest Coach in America.” And for Notre Dame men’s basketball, it has meant the most wins of any four-year span.

Brey’s evolution also helps explain one of the more unusual career trajectories in college basketball. The coach, a three-time Big East Coach of the Year and recipient of four national Coach of the Year awards, whose team has won more NCAA tournament games over the last four seasons than during the previous 14 combined, seems to be peaking near the end of his second decade at Notre Dame. And with a bevy of young talent, a sparkling new practice facility and a seven-year contract extension to his name, it may be that he’s just getting started.

Teaching moment

“Get up on him, Dane,” Brey shouts. The subject of his prodding on this Monday afternoon in October is Dane Goodwin, a 6-foot-6-inch freshman guard from Ohio who is one-fifth of the highest-rated recruiting class the coach has ever brought to campus. Brey is teasing his young sharpshooter about his effort on the defensive end of the practice court. “You can move your feet. I know you can shoot all afternoon.”

Brey likes to treat his players like men. He is honest and direct with them. When one of his guys isn’t playing well or makes a poor decision, Brey doesn’t scream in his face. More often, he has to coax his players to move on from the mistakes they already know they’ve made, rather than point them out.

When he needs to correct something, Brey uses humor. Jordan Cornette ’05 recalls getting called into the coach’s office after a rough loss his senior year. “If you could play the game as well as you give your postgame comments,” Brey said, “you’d be an All-American and we’d be the No. 1 team in the country.” Cornette, who now calls games for ESPN and hosts a morning television show in Chicago, laughed. But he also got Brey’s point. As one of the leaders of a struggling team, he needed to step up his game. “He was always taking those jabs at guys to fire them up,” Cornette explains.

For a lot of Brey’s players, his personality is what compels them to come to Notre Dame in the first place. When Kyle McAlarney ’09 first met Brey, he was struck by how normal the man seemed. A scoring machine from New York City, McAlarney had top coaches from around the country selling him on why he should play for their schools. He gravitated to the Irish head man because he seemed like a character straight out of his blue-collar Staten Island neighborhood.

“He’s a jokester,” McAlarney says. “The kind of guy that you’ll sit next to at a bar, and you’ll have a great time. He’s just a down-to-earth guy. You can’t separate him from a New York City fireman.”

But McAlarney knows better than anyone that Brey’s relationships with his players go much deeper than jokes. In December 2006, McAlarney, then a sophomore, scored 21 points in a home victory over Rider University. Hours later, he was arrested after police found marijuana in his car during a traffic stop in South Bend. The team’s starting point guard was immediately placed on indefinite suspension. A month later, he was expelled.

Crushed, McAlarney went home to Staten Island and started making plans for life after Notre Dame. Calls from other Division I programs poured in, and he was leaning toward Xavier. A few days later, Brey flew to New York to visit McAlarney and his parents.

Brey listened to the McAlarneys’ complaints about the way their son, who had never been in trouble before, was treated and about the harshness of the penalty. He told McAlarney that if he applied for readmission and returned to Notre Dame for his junior year, he could be one of the great stories of Notre Dame athletics. Before he left, he handed McAlarney one of his Notre Dame jerseys and told him to put it on and look at himself in the mirror.

The visit made an impact. So did a story McAlarney heard from his teammates.

“When he broke the news to the team that I was suspended, he cried,” McAlarney says. “That’s just me, a kid on his team, being suspended. I didn’t die. I was fine; I was healthy. But he cried.”

McAlarney returned to Notre Dame because he knew how much Brey cared about him. He graduated in 2009 as one of the most successful three-point shooters in program history. After nine seasons as a professional in the NBA’s development league and in Europe, McAlarney returned to Staten Island in 2018 and, partially inspired by Brey, is in his first season as the head coach at Moore Catholic High School, his alma mater.

History lesson

The McAlarney story represents a key element of Brey’s identity. The coach prides himself on being an educator. He tells his players that he wants to be their best teacher at Notre Dame, and the fact is that he spends far more time with each student-athlete than any individual professor does. By the time they graduate, Brey says his players feel more like family to him than pupils. “I’ve got a lot of sons out there.”

The focus on education stems from the fact that Brey never set out to coach big-time college basketball. When he graduated from George Washington University in Washington, D.C., in 1982, Brey’s coaching aspirations didn’t extend beyond local high schools. His career plan was influenced by three role models: His mother, Betty, a former Olympian who coached swimming at GW; his father, Paul, an athletic director at a high school in Maryland; and Morgan Wootten, the legendary head basketball coach at DeMatha Catholic High School, the D.C. basketball powerhouse where Brey starred from 1973 to 1977.

Wootten, who was enshrined in the Basketball Hall of Fame in 2000, saw something extra in his former point guard. He hired Brey right out of college to join his DeMatha staff.

In his first team meeting with a group of players who were staring at their third head coach in a little more than a year, Brey kept his message simple. 'You guys want to get back to the tournament. I think I can help you with that.'

“When you teach at a Catholic high school, they get their money’s worth out of you,” Brey joked last October while meeting with a group of about 20 Notre Dame students who were checking out the Alliance for Catholic Education’s teacher-training program. He recalled that, in addition to coaching for five seasons under Wootten, he taught six history classes at a time, worked 12 bingo fundraisers every year and earned an annual salary of $11,500. “I thought I was loaded,” he said.

Back then, his goal was clear: Land a head coaching job at a high school in the D.C. area and win enough games to stay there for decades, just like Wootten had. He was disappointed in 1986 when he failed to land the head-coaching gig at Winston Churchill High School in Potomac, Maryland.

A year later, something strange happened: Mike Krzyzewski invited Brey to join him at Duke as an assistant. Coach K and his staff had been so impressed by Brey when they recruited Danny Ferry out of DeMatha in 1985 that Wootten’s young assistant made the jump straight to the highest level of college basketball.

After eight seasons, six Final Four appearances and two national championships at Duke, Brey accepted the head-coaching job at the University of Delaware. He guided the Fightin’ Blue Hens to two conference championships in five seasons, then in 2000 took over a Notre Dame program that hadn’t played in the NCAA Tournament in a decade.

Brey’s tenure at Notre Dame can be divided into four eras. In his first team meeting with a group of players who were staring at their third head coach in a little more than a year, the new guy made no rah-rah speech and instead kept his message simple. “You guys want to get back to the tournament. I think I can help you with that,” Brey said.

He delivered. His first Notre Dame team went 20-10 and not only made the NCAA Tournament but won its first-round game. A year later, they returned to the second round, and in his third season, Brey led Notre Dame to the Sweet 16 for the first time in 16 years.

But then the second stage of his tenure kicked in. Armed with a talented roster and lofty expectations, Brey missed the NCAA Tournament each of the next three seasons. Looking back, it’s hard for everyone involved to put their fingers on what caused the regression, but whatever the reason, perceptions of Brey took a hit. “The natives were a little restless,” he remembers.

Then came a third chapter defined by excellent regular seasons that ended in disappointing March losses. From 2006 to 2014, the Irish advanced to the Big Dance six times but won only two games. Even more distressing, they lost five times to lower-seeded teams.

Brey blames himself for the March failures, saying his coaching was too uptight. “We couldn’t get out of the first weekend, and that became our burden,” Brey says. “That became our albatross.”

The albatross flew the coop in 2014-15, the season that ushered in the fourth and current era of Brey’s run. Led by Connaughton and Jerian Grant ’15, Brey’s best team went 26-5 in the regular season and then defeated Duke and North Carolina on consecutive nights to capture the ACC championship, the only conference title the Irish have ever won.

“Does our fan base really understand what that ACC championship was?” the normally modest Brey asks. “That’s one of the great achievements in our sport history here, not just basketball.”

After Swarbrick’s advice helped Brey guide the team past Northeastern in the first round of the NCAA Tournament, the Irish advanced to the Elite Eight, where they fell one basket short of upsetting an undefeated and supremely talented Kentucky team. A year later, Notre Dame became the only team to return to the Elite Eight. In 2016-17, the Irish made it back to the ACC title game and advanced to the second round of the NCAA Tournament. Then, last season, when Brey passed Digger Phelps for first place on Notre Dame’s all-time wins list, an Irish squad with a ton of promise — they upset sixth-ranked Wichita State in November to win the prestigious Maui Classic — was devastated by injuries. By season’s end, Notre Dame was the first team left out of the Big Dance on selection night.

In Maui, Five Overtime Mike was in his element. He wore shorts and a T-shirt on the bench, and after the dramatic championship game victory, he burst into the locker room shirtless with a lei around his neck, flexing for his players.

While that moment may represent the peak of Brey’s looseness, his ability to relax under pressure has always been a part of his personality. Jay Bilas, the longtime college basketball analyst who coached with Brey at Duke, points to an incident when the top-ranked Blue Devils were trailing on the road against Clemson. During a timeout, a cheerleader was waving a huge flag adorned with the Tigers’ paw print, brushing it against Bilas and Brey. “Mike looks up to me and kind of yells out, ‘We’re the only team in the league that doesn’t have a big flag.’ And then looks back into the huddle,” Bilas says. “I couldn’t help it. I started laughing.”

Years later, during a Notre Dame home game against Syracuse, Brey walked over to the Orange player at midcourt and made him a proposition. He said, “I’ll give you $100 if on the inbound pass you bank that thing in right here from out of bounds.” Irish associate head coach Rod Balanis, who has worked under Brey for 18 seasons, tells this story. “I was like, ‘Who would say that?’”

Keep calm and fire away

While the comfortable demeanor comes naturally, it also serves a purpose. Brey wants his teams to feel just as relaxed, to play their game with as little pressure as possible.

Tim Abromaitis ’10, ’11MBA, who spent five seasons in South Bend, went through a bad shooting funk during his senior year. Brey called him into his office and told him to stop thinking about the slump and just have fun playing basketball. To help him, Brey told Abromaitis he would make him laugh at the beginning of the next game. As Abromaitis and his fellow starters took the court, Brey summoned him back to the bench and asked him what kind of beer he’d been drinking on the night he was arrested. The previous summer, Abromaitis had been one of 44 students busted for underage drinking when police raided an off-campus party.

Abromaitis remembers laughing out loud as he walked back out on the court. “I’m pretty sure I got right back in rhythm,” he says.

Brey’s informality carries over to life outside basketball. One of the South Bend area’s most recognizable residents, he doesn’t shy away from the fan interactions that happen almost everywhere he goes. He eats breakfast at the bar of the same restaurant five or six days a week and has a few places he goes for dinner. Through his charitable work with Coaches vs. Cancer, he runs an annual South Bend golf tournament and has raised more than $3 million toward cancer research, most of which stays in the region. You’d be hard-pressed to find anyone who comes away from a Brey encounter with a bad feeling.

“I’ve just always wanted to be a regular dude,” he says. “It’s a high-profile job. It’s an amazing job, but overall in this profession we take ourselves too seriously.”

One thing that should be taken seriously is Brey’s coaching acumen. Bilas says people sometimes mistake his affability for a lack of competitiveness. And while the coach may not demonstrate the sideline intensity of some of his peers, his efficient, consistent offensive system is one of the envies of the coaching world.

His teams play smart, avoiding turnovers. They move well without the ball. They are exceedingly unselfish, creative passers. They shoot well from the perimeter and have permission to fire at will. They don’t run complex sets, and Brey doesn’t call the play from the bench on every possession. He teaches the principles and entrusts them to play free, confident basketball.

Last season, Brey hung a sign in the locker room giving two simple commands and an expectation: “Don’t skip class. Don’t throw the ball away. You and I will get along just fine.”

It’s a typically humorous message, but it speaks to what may be Brey’s greatest strength, even beyond his offensive wizardry: the straightforward yet enduring culture that has come to define his program.

In the “one-and-done” era, when top programs cycle in prized recruits who leave for the NBA draft without completing a full academic year, Brey intentionally pursues students who will fit Notre Dame on and off the court, building them up over time. The younger players learn from the seniors and juniors, then emerge as leaders as the cycle repeats itself.

“He’s got an uncanny ability to get guys to enjoy playing together,” says Martin Ingelsby ’01, the point guard on Brey’s first Notre Dame team who then served as an assistant coach from 2003 to 2016, when he took the head coaching job at Delaware. When faced with challenges running his own program, he says he always asks himself what Brey would do. Fans, Ingelsby says, don’t fully appreciate the job his former boss has done at Notre Dame.

Sitting in his office last June, Brey poses a trivia question: Name the only four men’s teams in the ACC who have played in the tournament title game over the past five seasons.

“Duke, Carolina, Virginia, and the CYO team from right here in South Bend,” Brey says, giving his visitor no time to venture a guess. He believes most college basketball fans wouldn’t be able to answer that question. “They’d get the other three,” he predicts. “They wouldn’t get us.”

There’s no anger in this Rodney Dangerfield act, but his meaning is clear: Notre Dame don’t get no respect. To wit, despite the successes of the last four years, the Irish entered this season unranked and projected to finish ninth in the ACC.

“I think we can be an afterthought sometimes, even with the national media,” Brey says. “But at the end of the day, they go, ‘There they are again.’ I don’t let it frustrate me or distract me. And we just keep grinding and doing our thing.”

Bilas, about as respected a voice as there is in the college basketball world, rates Brey at the top of his profession. “I’d put Mike up there with anybody,” he says. “There’s no coach out there I have more respect for.” Those really in the know, Bilas insists, agree with him. Coaches and scouts recognize the significance of Brey’s accomplishments at Notre Dame, he says.

The missing piece on his resume, of course, is a trip to the Final Four and a chance to play for the national title. More than a few people at the University think the next several seasons may give Brey his best chance yet.

The normally senior-reliant Irish are young this season. Only Rex Pflueger is set to depart in 2019, and T.J. Gibbs is the only veteran who had ever averaged even 10 points per game. But the freshman class is loaded; four of the five were ranked in the top 100 by the recruiting website 247sports.com. And it’s not just the freshmen fueling the hype. Sophomore wing D.J. Harvey, who had his debut season mostly erased by injuries, is healthy and extremely talented. Junior forward Juwan Durham, a former elite recruit who transferred from Connecticut, has two years of eligibility left beyond this season.

The group stacks up against the most talented in Brey’s tenure. And more and more, top recruits want to play for the loosest coach in America.

“Every now and then, I peek ahead,” Brey says. “I peek ahead, and I think, ‘Wow, how about this group?’”

Brey says he doesn’t obsess over making it to the last weekend of March Madness. But he admits that, when the time comes for him to walk away from coaching, it would be easier to go with a Final Four under his belt.

He has no plans to retire anytime soon. His energy level and desire are as high as they’ve ever been, he says. But when he signed a seven-year contract extension in April, taking him through the 2024-25 season, the thought crossed his mind that it could very well be his last new contract.

Brey will turn 66 in 2025. The deaths of his parents — Betty passed away on the day of the team’s 2015 tournament win over Butler; Paul died less than a year later — have caused him to spend more time contemplating life after basketball. “The one thing about coaches if you look at us overall: We don’t do a real good job planning for the next move. We kind of run right up into the damn wall one way or another and then go, ‘Oh hell, what else do I do?’ And I’d like to be a little more prepared.”

In the meantime, Brey doesn’t have much patience for discussions of legacy, even if he did release his autobiography, Keeping It Loose, in November. He’s not sitting in his office dreaming of a statue. When pressed on how he wants to be remembered at Notre Dame, the former history teacher’s mind goes to his student-athletes. “The most pressure I feel is: I want them all to have a great experience.”

Last February, as the Irish celebrated senior day by honoring the graduating players and their families on the court, Bob Farrell, the father of point guard Matt Farrell ’18, pulled Brey aside. A former high school coach himself, the elder Farrell thanked Brey for helping his son grow into a mature, responsible man.

More than his on-the-court victories, Brey says, it’s those moments he wants more of before he retires. And if he never wins a national title or captures another conference championship, he won’t spend years agonizing over what could have been. That’s not Brey’s style.

He’s Five Overtime Mike.

Kevin Brennan is associate director of marketing and communications at the Notre Dame Alumni Association.