Tell me, what do you make of this?

A sloth and an anteater walk into a library. . . .

A clever improvisational comedian or New Yorker cartoonist might play with concepts like “slow” and “nosy” to find the joke. But Jennifer Hunt Johnson took her material in a different direction and made instead a book of the kind produced by European craftsmen centuries ago. Wood and leather, heavy paper and complex stitching, woodcuts, engravings, the whole bit.

Hunt Johnson is a book conservator by trade, and explaining her connection to animals typically so far removed from northern Indiana requires a few paragraphs of roundabout explanation.

Last winter, brainstorming ideas for a Rare Books & Special Collections exhibit, Hunt Johnson’s colleagues, Notre Dame librarians Erika Hosselkus and Julie Tanaka, pursued a theme as surefire as any other to draw schoolchildren and families into the department’s showcase space on the first floor of Hesburgh Library: animals.

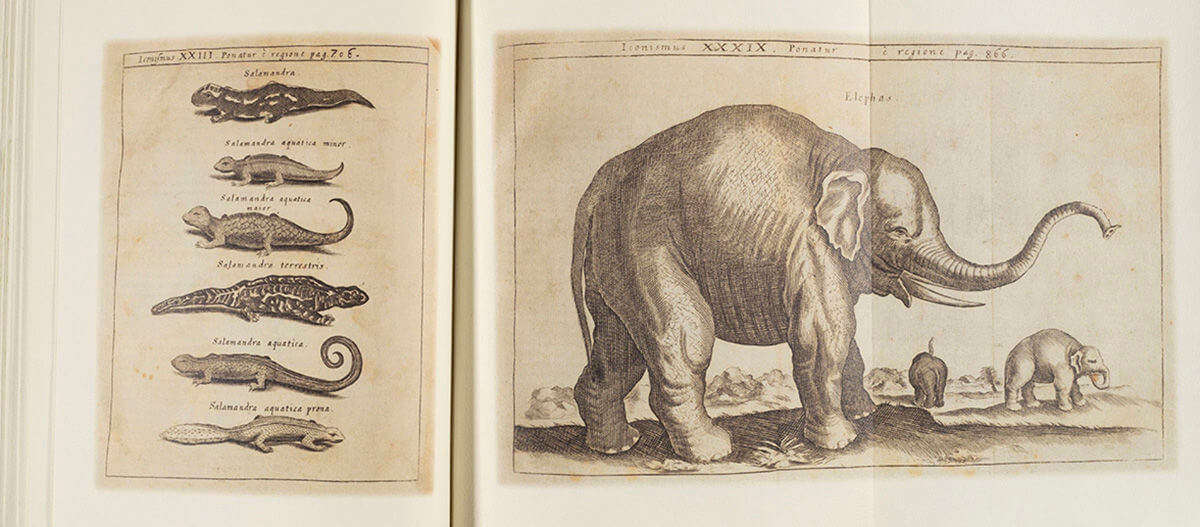

Natural histories were an emerging and increasingly scientific genre in the early days of printed bookmaking, the 16th through 18th centuries, and they were full of illustrations of animals meant to better acquaint readers with the global menagerie, ranging from the carefully observed and familiar to the spellbindingly imaginative and fantastical. Squirrels to sea monsters, if you like. (Is a unicorn really any more plausible — or preposterous — than a rhinoceros to readers who’ve never met either one? Natural historians of the 1500s sure seemed to think not.)

The point of any special collections exhibit is to share and spark curiosity in Notre Dame’s holdings of all kinds of unusual and unique books and other bookish materials: 132,000 printed volumes you couldn’t impulse-buy on Amazon and everything from colonial coins to Civil War letters that might support the University’s research and teaching strengths in the humanities.

Hosselkus and Tanaka were thinking big with “Paws, Hooves, Fins and Feathers: Animals in Print, 1500-1800,” their visual feast for the library’s mini-museum in the first eight months of 2020. They hoped to offer “something for everyone,” they wrote, “science, art, the early book, printing technology, history,” and they pitched it to teachers of such things in primary and high school classrooms across the region.

It was gonna be good. Partners included the local Audubon Society, Fernwood Botanical Gardens, the Snite Museum and an art historian from Saint Mary’s College. Notre Dame’s Museum of Biodiversity curated a “cabinet of curiosities” from its impressive cache of animal specimens to lend three-dimensional flair and evoke the personal collections of proto-ecologists.

Even the Potawatomi Zoo signed on for its own turn at show and tell, scheduling an on-campus appearance of Lennie and Olive, a sloth and a tamandua — a kind of anteater found in Central and South America — who could bring to life the Dutch naturalist Willem Piso’s work in a 1658 volume about the flora and fauna of Brazil.

Such events were to run throughout the spring semester and the summer. Then, COVID. The pandemic closed the university — and mothballed the librarians’ blockbuster gallery show along with it. “It was hard,” Hosselkus admits, especially after all that work above and beyond the typical call of a librarian’s duty. “Really pretty depressing.”

And yet: Before the disappointment, a midwinter “roadshow” visit with 1st and 2nd graders at South Bend’s Marquette Montessori Academy had demonstrated the potential of one of Tanaka’s ideas that was still under development: an early modern book not safeguarded behind glass and off limits to small hands, but one the kids could actually touch and pass around and flip through without worry of damage. Made of materials you could even smell.

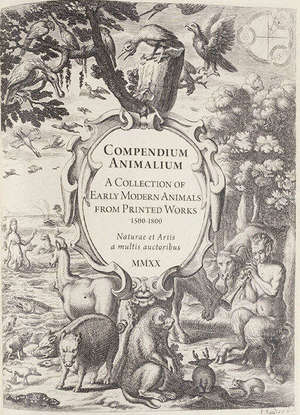

Working with conservation fellow Maren Rozumalski and digital project specialist Sara Weber, the group created a period-appropriate mockup of their own Compendium Animalium, a handy microcosm of the “Paws” exhibit in convenient book form. Weber photographed images selected from the original, exhibited works and created a layout they would print at the campus FedEx office on special heavyweight paper that has the look and feel of the rag papers used in bookmaking 500 years ago. They stitched together the sections and wrapped them in a simple “limp vellum” cover, a floppy tan calfskin that looks a lot like the slip-on, grocery-bag protectors you may have put on your own textbooks in grade school.

The Marquette kids got to interact with the book, ask questions and answer others. (“How would you draw a hippopotamus if you’d never seen one?”) Cowhide, they agreed, smelled funny and was just gross, but they were impressed all the same. “We always rely on the physical object and the experience of it,” Hosselkus explains, and this test of their prototype was an encouraging success.

“For us in conservation,” Hunt Johnson adds, the project of making an early modern book is an “amazing opportunity . . . to get the word out about what we do, to talk about how a book is made.”

The pandemic hit just as Hunt Johnson was ready to get started on the Compendium’s more up-market version, forcing her lab to close along with every other research and creative space on campus. So she turned her living room into a 16th-century bookbindery and documented every step in her process on the lab’s blog. Under these conditions, it takes a pro about a week to create a sturdy, “gothic style” book with an authentic, tight-back binding and a cover of red oak and vegetable-tanned goatskin.

Shaping the boards so the leather fit and the cover closed properly was the hardest part, Hunt Johnson found. Rozumalski added beautifully sewn blue and red chevron endbands, those raised bumps on the spines of old books, a hidden beauty of the craft long practiced by master artisans. Hunt Johnson pared and thinned the goatskin with knives and a tool called a spokeshave to create a “quarter leather” binding that left the wood uncovered toward the book’s open ends.

The result is a full sensory experience: rough paper and smoothed skin, a hint of oak as you page through the Compendium and contemplate the naturalists’ increasing realism across the centuries. Start with the heavily armored black-and-white rhino of Conrad Gesner’s imagination in the 1500s and make your way through the vibrant, hand-colored engravings of birds with “wonky” necks found in Mark Catesby’s studies of the Carolinas in 1750 — and beyond.

Though the exhibit is now history, Hosselkus created a digital version that captures these images and their fascinating backstories and presents them along with fun facts about the animals themselves. But visitors to campus in the post-COVID era might also see the 2020 facsimile of an early modern book that represents a true team effort to connect us with the material culture of a not-too-distant past.

Few have yet handled the finished product, but Hunt Johnson said the children’s enthusiasm from that wintry roadshow day was unmistakable: “You realize how much success the exhibit would’ve had.”

John Nagy is managing editor of this magazine.