G.K. Chesterton, the English Catholic convert and author who died in 1936, left an impression.

Even those who’ve never read a word of his writings may associate something with his name: his ponderous physical size maybe, or his quotable genius for paradox and expressing the essence of any issue. Or, his trouble keeping track of things. Constantly losing his walking canes in train cars or under hotel beds, for instance, this absent-minded man who stood firmly among the great Catholic intellectuals of the 20th century was quite capable of losing his way. “Am in Market Harborough,” he telegrammed his wife, Frances, in a story Chesterton told on himself in his Autobiography. “Where ought I to be?”

Nowadays a collection of Chesterton’s books and personal effects is safely in the possession of the University of Notre Dame (USA) in England, the official British name for Notre Dame’s London Global Gateway. This November, a delegation led by the University’s president, Rev. John I. Jenkins, CSC, ’76, ’78M.A., will travel to Fischer Hall, the school’s academic building near Trafalgar Square, to dedicate the G.K. Chesterton Collection.

While quantitatively small when compared, say, with the Chesterton holdings of the nearby British Library, the items displayed in Fischer may reveal the man’s warmly unique creative genius better than any other collection. Rev. Jim Lies, CSC, ’87M.A., the gateway’s interim senior director for academic initiatives and partnerships, says the goal is to create a space that serves as an archive for scholars and a mini-museum for fans as Notre Dame builds relationships with Britain’s universities and Catholic community.

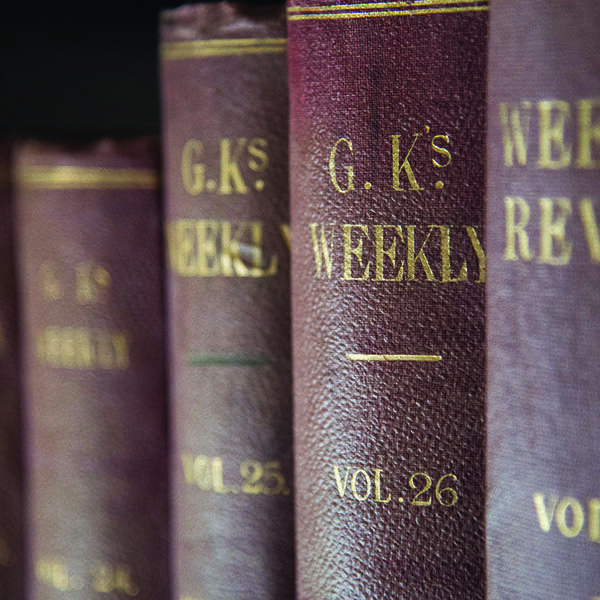

Start with the desk and chair from which Chesterton conceived much of his literary life’s work: more than 100 books, reams of poetry, five novels and a short-story corpus that has left us eight years and running of the Father Brown detective series on BBC One. That doesn’t include the 4,000-plus columns and essays he penned for major London newspapers and his own G.K.’s Weekly across a 40-year journalistic career. Dale Ahlquist of the Minnesota-based Society of Gilbert Keith Chesterton likens that output to one essay a day for 11 years.

“If you’re not impressed,” Ahlquist writes, “try it some time. But they have to be good essays — all of them — as funny as they are serious, and as readable and rewarding a century after you’ve written them.”

The collection’s Corona typewriter wasn’t Chesterton’s. It belonged to Dorothy Collins, his personal secretary, regarded as a daughter by the childless couple. “Chesterton was not capable of typing,” notes Aidan Mackey, the 97-year-old collector behind this collection, who befriended Collins late in her life and received many prized items directly from her. But, Mackey suggests, a rare, practical facet of the man’s scatterbrained brilliance was his ability to handwrite a letter and dictate a book to Collins at the same time.

There’s Chesterton’s lumpy black hat; some walking sticks he didn’t lose; his academic gown from the University of Edinburgh; the rosary from his nightstand; his spectacles; a selection of paintings, drawings and puppets he made as a onetime art student who never attended college; his wife’s collection of miniature dolls; a fountain pen.

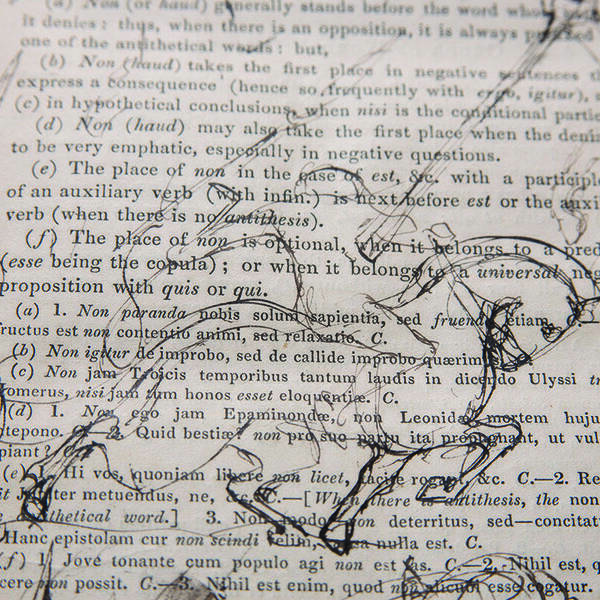

And books. Books he authored and books he didn’t, but they’re his because he scribbled and doodled all over their pages, as alluring a window into the inner workings of his mind as one could hope to find.

“I’m sorry to criticize him, but he was a vandal with books,” Mackey, a retired schoolmaster, says in a video interview available at london.nd.edu. “He would tear out the blank flyleaves to light his little cigars, and his books, at school or at home, wherever he was, [were] covered page after page with extravagant doodles and so on. Not just in the margins but right across the text.”

As a collector, Mackey was no dilettante. During the 1950s, he edited a publication called The Distributist informed by Chesterton’s political and economic writings, which rejected both communism and capitalism. Years later, Mackey’s kids grown and gone, he converted the ground floor of his home into a Chesterton reading room. All the while, he spent what he could on books and memorabilia.

At one point, Collins brought him what she had left after the British Library gathered what it wanted. Then one day the library called and asked if Mackey would take more — eight mammoth cases of items it couldn’t use.

“I’ve still not recovered from that,” Mackey deadpans. “This great richness of stuff.”

That “stuff” may be the strength of Notre Dame’s collection: the objects closest to one of modernity’s great defenders of objectivity, who wrote at a time when age-old understandings of reality and the natural law were being called into question in the popular mind.

Chesterton liked things. He believed in them. “One of my favorite lines is from a letter he wrote to his fiancée before they were married,” says theology professor emeritus David Fagerberg, who teaches a course called Chesterton and Catholicism. Writing after work at the newspaper, the young journalist reflected on the inkstains covering his fingers and shirtsleeves.

“And he said, ‘I like Cyclostyle ink. It’s so inky. There’s no one who loves things being what they are more than I do. The fieriness of fire, the unutterable muddiness of mud.’”

Fagerberg says that such statements of objective truth, when applied to controversial subjects and moral questions, are no less provocative today than they were in 1900. “How would Chesterton most bother us?” Fagerberg asks. “He believes there’s a truth out there to be found.”

The writer knew he’d feel at home at Notre Dame ‘even if it were in the mountains of the moon.’

In search of a lasting home, Mackey’s collection moved first to the Centre for Faith & Culture in Oxford and then to the library of the Oxford Oratory, a prominent locus of English Catholic life, before finding its way back to London and Notre Dame. There Father Lies and Professor JoAnn DellaNeva, then the gateway’s academic director, happily received it, with the agreement that it remain forever in Great Britain.

Lies calls the acquisition a “nice match” for a Catholic university that aspires to leadership in global higher education, but the connection is more personal than that. For six weeks in the fall of 1930, Chesterton was a visiting professor at Notre Dame, lecturing on Victorian literature and history. He drank basement-brewed beer in South Bend speakeasies and the top floor of a Sorin Hall turret, where he told stories and recited poems. He attended the first-ever football game at Notre Dame Stadium and balked at the raucous applause and chants when he was introduced to the crowd. “My, they’re angry,” he said to his driver. “Angry?” the Irishman replied. “Golly, man. They’re cheering you!” Chesterton found that hilarious. He later wrote a poem, “The Arena,” about the game he watched that day.

A biographer wrote that when he received the invitation to come to Notre Dame, Chesterton wasn’t sure where it was but knew that with a name like that he’d feel at home there, “even if it were in the mountains of the moon.” His intuition proved true — and the feeling mutual. At the end of the lecture series, Father Charles O’Donnell, CSC, the University’s president, awarded the writer an honorary degree.

Though the coronavirus pandemic slowed the preparation of the Chesterton Collection, it is already fulfilling its academic purpose. Brady Stiller ’20, ’21MNA wrote his senior theology thesis, “Vocation As Romance Story,” based on a close reading of 20 of Chesterton’s books and what he found in the collection.

The valedictorian of his undergraduate class, the biology-theology major had spent the fall of his junior year in London. He made pilgrimages to the writer’s home, parish and gravesite in Beaconsfield; to his favorite London pubs; to Fleet Street, still a metonym for British journalism. At semester’s end, Stiller traveled to the Oxford Oratory.

Back on campus the following spring and discerning a possible vocation to the priesthood, he began writing down ideas he eventually thought he could shape into a thesis.

“I’m arguing for a way of seeing the world,” Stiller says of the project, which explores objectivity and subjectivity and how we contemplate the meaning of our lives. “I’m arguing that each of our lives is a story, and that God has the best story that he wants each of us to live into. . . . And I found that Chesterton very much had the language to discuss all of this.”

At the heart of Stiller’s research during a senior-year return to London was the author’s toy theater, a popular pastime of Chesterton’s era even among writers like Robert Louis Stevenson and H.G. Wells. The theater formed the backdrop of Chesterton’s earliest memories, and he would continue to write plays and create cardboard characters and scenery throughout his adulthood. For him, the stories that it brought to life opened onto such supernatural wonders as the Incarnation. Stories within a greater story.

This past April, Stiller signed a contract with a publisher, Word on Fire Academic, to turn his thesis into a book. His adviser, Professor Fagerberg, says the author whom C.S. Lewis credited for his own conversion to Christianity — long neglected by philosophers and theologians because he didn’t join their academic guild — is ripe for scholarly exploration. He knows of three prospective doctoral students who want to write dissertations on him.

Given the chance, they’ll want to go to London to take a look at Chesterton’s things.

John Nagy is managing editor of this magazine.