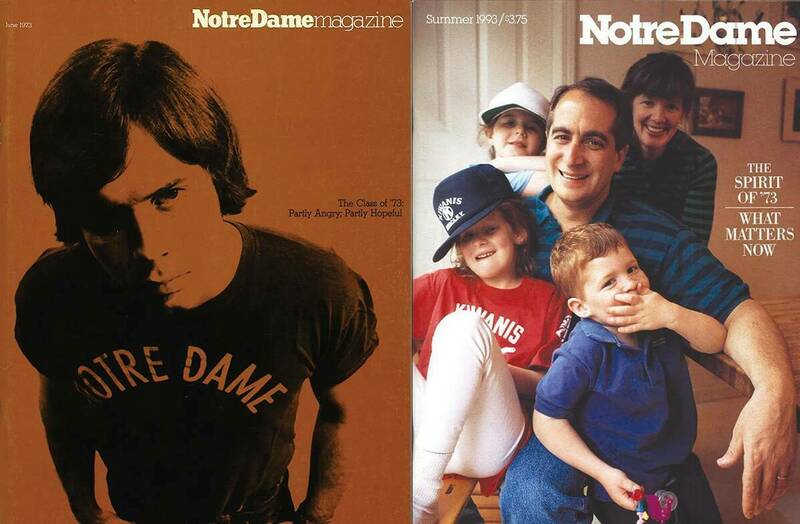

Life In Transition

By John Walsh ’73

A resident of Baltimore, Md., John Walsh has managed WSND, the student radio station, during his last two years at Notre Dame. He will graduate with a degree in mechanical engineering and is seeking a job with a radio station.

With all the changes in attitudes and ideals taking place out in the real world, it was only to be expected that Notre Dame would change, too, even if in its own halting way. But the changes taking place here were a good deal more sweeping for the campus than anything the rest of the world has to offer. While these changes were ending an ice age of discontent for students, they only seemed to destroy the faith of conservative alumni. But in spite of the change and its detractors, the spirit of Notre Dame has maintained its position with respect to a changing world, even if it lost its anchor in the past.

Life here in the fall of 1968 was in transition; the last few die-hard rectors were patrolling halls and demanding student sign-ins. The old Notre Dame of dress codes, lights out and mandatory Mass was gone already. Within a year, the rest of the old regime followed. Such agents of corruption as beer and the other half of the human race made their entrance into the dorms. To listen to alumni and some University leaders, the end was near. It was these conditions that greeted 1,500 freshmen that year who came to join the amorphous mass known as the student body — and began standing in lines. Linestanding is a tradition that must predate football or bad weather.

Amidst the waiting, classes, and bothersome but unavoidable work, there was and is some time available for goofing off, outside activities and getting used to Notre Dame. And frankly, for a high school kid, this getting used to could be pretty alarming. There was a movement in those days to impeach a student-body president for radicalism; today, the students cannot elect one.

The war was quickly becoming an issue; there were small groups of radicals (admittedly smaller and less vocal than elsewhere) who were giving peaceful, middle-American Notre Dame a radical tinge. Everyone was lining up on either side of issues, and debates raged constantly. Things seemed to be worth fighting for, but Kent State and Jackson State made most people sure that they should go on debating.

With these serious matters on the surface, what was the typical student thinking about back in the dorm? Apparently nothing, as many of the freshmen and sophomores on campus were busy with water fights, shouting matches, firecracker-throwing and basic production of noise or nuisance. And there was always a mandatory panty raid on Saint Mary’s thrown in. This adolescent behavior was attributable to absence of social life, but with female presence increasing, a new cause must be found. This might not have been much of a life, but blended with study and classes, the days were busy if not enjoyable.

Escape was sought almost universally and came in the form of a forbidden chemical presence in the body, off-campus living, vacation or extracurricular activity. The first three were, in order, forbidden, inconvenient and too infrequent. The last was handy, and far from the madding crowd.

The school maintained itself in this tenuous state for about two years — up through the Great Strike of spring 1970. This seemed to wash the campus clean of concern. A couple of liberal student body presidents later, there had been a lot of talk of great change and that is all. Back in the dorm, the average student was slipping away, his basic conservatism shining through, and it was all over but the shouting. By the end of the third year, radicals were museum pieces. Student demands had settled down to the niceties of life and had been won during the conscious years — alcohol, parietals, and the sanctity of the private room. Speaking positively, the student body began to see issues more clearly and less emotionally. They admitted to themselves that they were not activists and saw that student politics and verbal radicalism without action are a farce.

For all the talk of traditions and rules (especially for the 15-minute variety) by the University hierarchy, the students did throw their weight around for a while and things changed. Policy statements were tough, but the result was rough rules, easy living. For all the past drama, basically the student’s life within the dorm is his own.

With issues dead or dying, the calm on campus approached coma. The focus of activity shifted to the circle of friends and outside activity. With the exception of lucky individuals who happened to land in the midst of a homogeneous group of neighbors, the dorm was not the center of life. But losing touch with this “normal” hall life is not necessarily a bad thing; it can be very good. Forming a circle of friends other than neighbors, a hand-picked crop, gives the opportunity to test the theory that what you really love about Notre Dame is the people; it is, if only because it is hard to find much else to love. Another plus in shifting activity outside the hall is that standards of good living in the dorm often centered around noise, kegs, pranks, and delirium; subtlety is not its strong point. If no one does not fit the mold, it is hard to say whether hall life is boorish or the nonconformist is a bore.

Through all the tensions on campus and the following calm, the average student had remained the same; and now with the gripping issues gone, he did not even have to take sides. The basic factors in his life were there as always. The education remained as good as the student made it — and as hard or easy. The social scene was slowly improving. And athletics, whose merits and benefits to the University had been questioned, made a comeback. They are now just another part of the order of things; not first or last. Reality has replaced ideals.

Upward mobility in any organization puts one in contact with the ruling class. Even from the top of so transitory a structure as a student activity, a person can begin to study the visible but obscure body known as the administration. Condescension; that was the story in a word. When it came to dealing with the students, they stooped to conquer. Most students simply wanted to live without interference; they were a basic nuisance to the University structure, but they could be handled. The student politicians, organization heads, or those with programs provided more of a problem but they could be handled, too. They could quite painlessly be put off until they had an exam or a vacation or the school year ended; they were delayed into oblivion. And since the students have to graduate sometime, the status quo can outlast them.

Stable operation is most important to the University; therefore, much of its machinery grinds along inefficiently for fear of rocking the boat. For the sake of the students, lip service is paid to the future. For the sake of the alumni, homage is paid to the past. Then the administration does what it had planned, and calls it the general good.

At some point, however, pressing involvements on campus fade, and the student faces the final fact that he must leave. For all the criticizing and complaining, imminent loss of security makes the place look pretty good. At least here, there is the certainty that the big problems are often no more than points of discussion. And this is valued even if it does go along with firecrackers, food riots, condescension and Swiss-steak espagnole in the dining hall.

But liking Notre Dame definitely involves more than an attachment to security. The good friends that have been met here are a primary consideration; they will be missed. Another is the belief that probably never again will there be an opportunity to live in an environment where, for all its basic homogeneity, there is room for the acceptance of tremendous diversity. From the point of view of personal development, Notre Dame provides each person the opportunity to have his high horse shot out from under him. A person leaves here knowing that there have been a lot of good ideas in the world, and it has to be conceded that his are just some of the better ones. But most of all, there is the fact that there are people striving to make Notre Dame represent order amid chaos. And this striving must be paying off because this place is producing a lot of good people, and a few great people, all of them better for having been here.

My Four Years Here

by Greg Stidham ’73

Greg Stidham is a former editor of Scholastic from North Olmstead, Ohio, and will attend Toledo Medical School after graduation.

Anger led me sometimes to slight excesses of language. I could not regret them. It seemed to me that all language was an excess of language.

The words are from Molloy, a book by Samuel Beckett. Beckett — the ultimate skeptic of this power of language — he was terrified by the inadequacy of words. Still, he wrote. I, too, am skeptical of words. I am expected, I suppose, to write about Notre Dame, to write about my four years here, now, as I leave. And so I write, knowing that all language will be an excess of language.

The quote from Beckett mentions anger. I have felt anger, at times, at Notre Dame. It angers me when members of the community have such difficulty resolving differences; that has been an oft-repeated story in the last few years.

I have also, at times, felt pride because of Notre Dame — less often because of its football team than because, for example, of Hesburgh’s courage in the Civil Rights Commission. I am proud because there are people here who are not embarrassed to try to be decent.

I have felt the warmth of the relationships I have formed here. With those whom I have lived with, with faculty, and so on.

As I leave Notre Dame I feel gratitude — I must say this — gratitude to the faculty here. They are scholars . . . they are human beings . . . many have been good friends. I must say that as far as I am concerned, the faculty at Notre Dame are Notre Dame.

All of these sentiments and more have found their way into this chaotic emotional potpourri.

. . . I must stop myself; already my language becomes excessive. None of these things matter, as valuable as they are. Notre Dame does not matter, finally, either. I think, and I tremble as I do, that the experience of these four years will matter only if it has given us something that will endure within us and that we can share afterward. We must leave Notre Dame as people with compassion, with conviction, and with understanding . . . but, most of all, as compassionate people. We leave Notre Dame for a society that has disappointed us and a world that, finally, has nothing to promise. Dorothea says in Middlemarch, “What do we live for, if it is not to make life less difficult for each other?” Indeed, that is all that matters — the possibility of making life a little less difficult for someone else. And Notre Dame, finally will have mattered only if it has made that possibility a little more tangible for each of us.

Then There Were People

By Paul Dziedzic ’73

Paul Dziedzic is a former director of the Ombudsman office and comes from Lacey, Wash. A government major, he plans to work in Chicago next year.

College certainly isn’t a place where you grow up. My apologies to hopeful parents and eager freshmen. I came to Notre Dame 5’10” and thanks to my transition from tennis shoes to boots I now challenge 5’11”. Those wonder years ended back in high school, and if you aren’t having problems with doorways or playing center by now, you never will — so you can just buy the medium and stop worrying about growing into the extra-large.

College, and our Notre Dame, is a locus of deeper things. It is the time when the hodgepodge of bombarding influences — teachers, television, parents, friends, books, and back seats — comes under scrutiny. This is not growing up, but filling out. Growing up smacks of parents and puberty; of rapid, bewildering change; of a continual “you’ll understand.” While the supple ten-year old is becoming the gangling sixteen-year-old, the mind and psyche open to a torrent of influences, pressures, and drives. A lot is experienced, but little is understood.

I imagine that this suffices for my contribution to armchair psychology. Having illustrated my appreciation for the wider issues and scope of my efforts, I can get on with the egocentric business of sharing what that process of scrutiny and filling out was for me at Notre Dame.

The Notre Dame part of that phrase is most crucial. There is a favorite trivia question made among departing seniors and other sentimentalists that goes, “What is it that you will miss most about Notre Dame?” The football weekends and even academic stimulation fall far behind “the people.” For fear that “the people” of Notre Dame is becoming trite, I will assert that it is because of them that I, and many of my friends, were able to face the questions about ourselves and begin to fill out our lives. People who trust and encourage and expect a lot — they are the people who made it happen and they are the ones who will be missed.

Several examples out of my four years here will serve as illustration. Freshman year was the year of the strike against United States’ involvement in Cambodia. My year had been devoted to studies only to the extent that I got good grades and that they didn’t get in the way of my diversions. It was the prime time for diversions — spring — when the strike hit; but I found myself compelled to rearrange that lifestyle that survived geology, calculus, and first-semester finals. Even before I could reason it out, I knew that I would have to commit myself to a moral rejection of so much disregard for life and dignity. I also knew that it had to be as much as I could give, or it would be a flat experience. When you make that kind of commitment, it is comforting to know that there are people who understand and expect you to go more than halfway. The campus was filled with those people and maybe that is why we seniors will remember May of 1970 as the high-water mark of community at Notre Dame.

My first several years were also marked by a lot of questions about religion and a possible vocation. I ran into some very dedicated people who showed me a life of faith and love that challenged me. For a second time I was faced with an uncertainty about what I should do; but more than that, what I was. The question could still be up in the air except that I tried it and found that that particular way wasn’t for me. Again it was a few of those special Notre Dame people who showed me I had strength to try that road, and the strength to leave it when it didn’t work out. A big question mark was removed because of the encouragement of those friends.

That decision was made in the privacy of close friendships, but the final experience I will relate took me into a much wider forum. I had been marginally involved in student government during my sophomore year when I was named ombudsman for the upcoming year. It was not long before I was being asked whether I was going to run for student body president. The questions were flattering but the prospect was dim and foreboding. Working as Ombudsman I found that I could handle just about anything the student government situation threw at me. As my confidence grew, I found that I was not short on ideas about how Notre Dame could better live up to her potential. There were still a lot of questions and reservations. The resolution came when I was challenged by, “If you don’t try, how will you ever know if you could do it?” Mike Sherrod and Patty Burger encouraged and had faith in me but, more than that, they expected me to do it all the way or not at all.

Mike and I made the runoffs against King Kersten and Uncandidate the Cat. We had the distinction to lose bigger than any ticket in student government history. We also had the satisfaction of knowing that we had given as much as we could. For four weeks we did little else but challenge our fellow students to demand of themselves and Notre Dame as much as they could. It is one of the richest and happiest memories I have.

I know of kids who were irrevocably alienated by the futility of the 1970 strike and the horror of Kent State. There are those people who have lost any sense of God because of unfilling experiences with His institutions. And it would be easy to be bitter about losing 2-1 to anybody — let alone a king and a cat. From where I sit, however, it looks a lot brighter than any of that. Those past battles all counted in the win column because each one helped me to know myself, to fill myself out. They were not the only ones. The other, unnumbered situations and valuable friendships that attended them make this a way of approaching life, not just a set of experiences. I can only hope to find friends in the years ahead who can help me challenge myself and life’s puzzles like the people of Notre Dame have.

This spring I received two cards. One quoted Hungerford, “… only the brave dare look upon the gray — upon the things that cannot be explained easily, upon the things which often engender mistakes.” The other just said, “He made them look within, and decide for themselves.” They were both made by the hands of very special Notre Dame people. Those cards didn’t make it all worthwhile, however. They didn’t make the decisions right. Those decisions were worthwhile because I knew at the time that they were the right ones. Those special Notre Dame people — their understanding, their faith, and their encouragement to do it all the way or not at all — made it possible for me to follow through on what I knew was right. They made it possible.

One Student Critique

By John Abowd ’73

John Abowd is a senior economics major who will continue in economics at the University of Chicago. From Farmington, Mich., he edited The Observer for two years.

The most misunderstood student at Notre Dame — and every other university, I suspect — is the student who feels obligated to offer his criticism and suggestions for improvements before he graduates and moves into either the real world or a permanent position in academia. I don’t mean single-shot condemnations of the way the University is run, but, rather, ongoing discussion of the University’s priorities and government. The student critic is often misrepresented as an unfortunate soul who will think fondly of Notre Dame in ten years when he has finally realized all that the University meant to him.

It is virtually impossible to complete four years here without being deeply touched by the people with whom one has lived and worked and studied. Thus, the student critique is motivated not by hatred for the institution that provided these four years of learning but by a curious kind of puzzlement at how Notre Dame can work so hard to attract the type of student that is capable of intelligent discussion of the goals of the university, then work so hard to discredit that discussion.

This is neither the time nor place for specific consideration of the issues that have generated student criticism. Instead, we should consider why the student critique is a necessary and vital part of any university community. I want to do this for no other reason than to share with some doubters the reassurance that all is not lost when The Observer prints a critical editorial or Scholastic challenges the basis of University government.

There are three very good reasons to promote and consider seriously the student critique. The first is economic. The student critique suggests ways in which the University might improve in the eyes of its primary customers. It’s a buyer’s market for higher education in the United States. This means that an institution that wants to survive must make a real demonstration of its desirability to prospective students.

The student who doesn’t think Notre Dame is worth improving won’t waste his time making suggestions. However, the suggestions of those students who have taken the trouble to research their positions are surely the best market information this University will be able to find. Where else but from a student could a person whose Notre Dame has no place for women find out that the place really is much improved by their presence and active participation.

The second benefit of the student critique is educational. It provides a valuable opportunity to systematically analyze a self-contained political and social environment. For the rest of our lives we will have to make decisions about the quality and governance of the communities in which we live. If the University teaches us that such decisions are merely idle exercises in futility, then it must take more than a small measure of responsibility for any poor citizens it has sent out into the world.

The last benefit is professional. The student critique can be a valuable, substantive document deserving of all the consideration that contractual research receives. To argue otherwise confuses the relationship between professional training and guided research. Students are able to make worthwhile contributions to University operations in the area of their professional training. The fact that a project was undertaken as an educational endeavor does not automatically make it ordinary work. And the fact that a project is ordinary work certainly does not automatically mean that it is of inferior quality.

It must be my social science training that makes me think that these points should be obvious to even the most casual observer. They apparently are not. But it is reassuring, from a student viewpoint, to see that Notre Dame has moved a long way toward the inclusion of the student as a full partner in the University community. Every time I think we’re close enough to celebrate, though, someone slips and sets the whole process back a year (or two or three).

Perhaps the most heartening observation in my four years was watching the newly acquired zeal exhibited by the vice president for student affairs and his staff in the beginning to seriously address issues of genuine concern to students. He has to do some dirty work; and it would be inaccurate to say that I would be pleased if the progress stopped at its present state of development. Nevertheless, there was a time when I thought I’d never see someone go well out of his way to solicit student input on every major decision and minor ones as well.

For several years people have asked me: “Why did you pick Notre Dame?” Nobody ever got a straight answer and I doubt that anyone ever will. I don’t hate the place. I have two brothers here and a third on the way. I would surely have told them of any hate.

However, there was a certain disappointment in knowing that student critiques still didn’t receive all the consideration they deserve. But there is also a lingering satisfaction in knowing that the people I have known at Notre Dame have considerably shaped the direction of my life.

The only answer I ever give anyone who asks that infamous question noted above is: “Notre Dame is like a good wine — it improves with age.”

A Fine Catholic School

By Jim Fanto ’73

Jim Fanto is a resident of Lonng Beach, Calif., and is an English major. He will study in France following graduation.

I feel uneasy about describing my experiences here. I fear sounding nostalgic. Yet I realize that it is almost impossible for any senior to write about Notre Dame without some trace of that irritatingly sentimental emotion. I am also distrustful of words which attempt to describe the University and life at du Lac. I have read and heard many words, which ostensibly describe what Notre Dame is like, but which seemed to me to have little connection with the reality of campus life.

Each vacation, at least once, I am introduced to somebody as a “Notre Dame student.” That always triggers replies from new acquaintances like “you are at a fine Catholic school” or “that is a school with discipline,” which never fail to make me wince.

Administrators, faculty and students frequently describe Notre Dame with high-sounding terms. Since I have worked for campus magazines, I, too, have used the standard Notre Dame clichés and invented some of my own. The description of Notre Dame as a “Christian community” appears constantly in conversation, campus publication articles and administrative speeches. Other words create the picture of a coed campus which possesses attractive residence halls, an exciting intellectual atmosphere, and, to suggest that this picture is more fictive than real — a bookstore whose high prices keep tuition down.

I don’t like words which create some rosy vision of Notre Dame. What I know about Notre Dame clouds this vision. The term, “Christian community,” must be stretched, indeed, when it is applied to a group of people which includes a number of students who are not Christians, although they may have been upon entering Notre Dame; some administrators whose decisions seem antithetical to Christian principles; and students and faculty who know few people outside of their department, hall or class. The halls are often uncomfortable to live in. Most off-campus students were not forced to move from the halls. Some classes at Notre Dame are dull, but some professors are incompetent and some students are lazy and dishonest.

I am not substituting a vision of Notre Dame full of incompetents, sinners, or manipulators for a rosy du Lac. I dislike all general descriptions of Notre Dame because I have seen people here adopt the pictures generated by the descriptions as the reality of Notre Dame. But then, people ignore anything which conflicts with their vision.

Since I distrust general descriptions of Notre Dame, I cannot say that the University is this or that type of place. A friend of mine, a Notre Dame professor, once told me that he had no feeling for the University as an institution. Whenever he thinks about Notre Dame, he remembers his friends and associates. I agree with him. Notre Dame “means” to me the people I have met here during my undergraduate years.

The problem with writing about the people one feels fondly about is that one invariably sounds nostalgic. My first thoughts go to my teachers, for example, my academic advisor who always saw some worth in whatever intellectual expression I made — no matter how inarticulately I managed to express myself. I also recall a professor whose encouragement and criticism of my classwork awakened my interest in literature and other disciplines. I know other professors who remained after class to answer my questions, loan me their books, and to help with any problems I had.

Whenever I think about Notre Dame, I immediately think of my roommates. I lived with three other students for the last three years — one year in the halls and two years off campus. The off-campus years were the most interesting for all three of us, even though it may seem odd to call years full of cooking (or learning to cook), cleaning a house, washing clothes and shopping interesting. But we probably learned more about each other with our off-campus suds and cooking oil than if we had remained on campus for all four years. When I talk about my roommates, as with my other friends, words seem inadequate.

These people and others comprise my “picture” of Notre Dame, which is composed not without a little nostalgia and hopefully without any hidden message that Notre Dame is this or that type of school.

Pursuing Truth, Beauty, and Goodness

By Linas Sidrys ’73

Linas Sidrys is a senior premed major who will attend the University of Chicago Medical School next fall. A former president of the Lithuanian Club and editor of the Science Quarterly, Linas lives in Streator, Ill.

Some students enter the University of Notre Dame thinking already of the day they leave it. The four undergraduate years are regarded as either a stepping-stone or as a stumbling block in their plans for medical school. There is a very great tendency, more than in any other major, for the student to lose himself in the workaday world; the world of total work, with the belief that this is the right and necessary thing to do.

On entering the University, most premeds restrict themselves entirely to the close and direct problems which confront them: required science courses, quizzes, exams, papers and grades. Premed students study as though their lives depend upon it — as in a sense they do. They work hard and worry even harder. However, those questions with which intelligent men have grappled throughout every age and in every culture, and which should hold a preeminent place in the minds of every student who enters the University, are often ignored.

For example, the typical premed concentration on grades, supposedly the indicator of educational progress, limits or destroys a truly liberal education. The student is unable to use the freedom of their undergraduate years to stop and explore his own insights into the basic questions, to determine the relationship of one thing to another, to consider what really constitutes a good life and to ponder its personal applications. In the accelerated schedule it may seem that the system of grades and exams is forcing a pseudo type of learning on everyone, eliminating any real, in-depth understanding.

The complex problems of modern society cry out for excellence. The lack of intelligent idealism and liberally educated medical doctors has had serious and deadening consequences for the human person, the medical profession and all of society. Abortion is only one example. Premeds who see only their own immediate goals become doctors blind to their family, social, political and ethical responsibilities. Thus, ironically, it is because the physician’s liberal education, communication and social organization have remained in the horse-and-buggy stage that the fond image of the concerned horse-and-buggy doctor has given way to that of a complacent, golf-playing specialist.

The central dilemma of how to make the best of the indispensable undergraduate years is similar to the query posed in How to Read a Book: how can a book teach one to read insightfully when the undiscerning reader can only but misread this book also? How does an educated person oversee his own education intelligently?

The sources of personal motivation for a liberal education can vary widely, but the primary interior spark and active guideline of Catholic education are to be found in the theme that has motivated Christian learning from the very beginning — faith seeking understanding. The direction given by this goal, a goal evident in the past and present of this University, constitutes the particular value of the Notre Dame tradition.

Those science students who share this motivation may easily enroll here in philosophy, literature, history or government courses with real substance, and with professors who truly “love wisdom” and are able to communicate both the love and the wisdom. With such professors’ aid, perhaps the enquiring student will realize that to be fully human requires one to awaken all of the multifaceted dimensions of reality, by the serendipitous inspiration of the spirit, the hard labor of the intellect, and the openness to one’s personal experiences.

However, as a Notre Dame philosophy professor quizzically asked, do students live in dread of the next exam really understand the meaning of Socrates’ dictum: “The unexamined life is not worth living?” The student who misunderstands and turns away from the philosophical act, the aesthetic act and finally the religious act, turns away from the pursuit of truth, beauty, and goodness. He loses part of his being as a human creature, in that he loses the chance to be a more complete person; the ability to love well and wisely, to reason deeply. To do great things he may have been called to do during his lifetime.

Perhaps it may be said that the premed years of freedom are an intensification of the entire educational decision: to the extent that a person succumbs to the distractions of his immediate surroundings, or for fear of the future complacently accepts a life that is half-asleep, merely terrestrial and woefully limited, he will miss being all he can be, and understanding what he should be; and also lack the clear ideas and forceful motivation that would better enable him to serve the common good, in his profession and everywhere else he is needed.

One Last Gripe

By Floyd Kezele ’73

Floyd Kezele is a senior government-urban studies major from Gallup, N.M.

In my four years at Notre Dame I have heard and personally voiced many criticisms of the place. Forthwith, my last gripe as a student; my first as an alumnus.

Notre Dame must face up to itself; it must identify itself, its goals, its shortcomings. Notre Dame must be the Notre Dame that it is rather than the Notre Dame people think it is, or would want it to be. This process could begin immediately and should include all facets of the University — administration, faculty, students and alumni. Illusions must be destroyed.

Notre Dame needs to be defined — by all participants. For example consider the administration’s P.R. gimmick — “Christian community.” Do not despair, Notre Dame has not yet escaped its role as the Catholic university. Indeed, at times, it shows signs of regression.

A Christian nature implies caring for others, but more importantly the safeguard against using others for one’s own purposes. Father Brennan used to say that a true Christian recognizes the individuality of each person; the same is true of the groups which are at Notre Dame. Instead of maintaining or imposing Notre Dame’s monolithic tradition on the individual, we should realize that it is differences which make Notre Dame what it is. The alumni and administration are unfortunately guilty of ignoring, if not destroying, diversity rather than answering it. Rather than building one from many, attempts are made to find niches for everyone. Such a process will not work; it stifles, it is expedient rather than natural.

Tradition at Notre Dame, as far as students are concerned, is often punitive when it could and should be rewarding. Instead of providing rational arguments to counter student proposals, students are more often than not faced with the common argument — it isn’t in the tradition of Notre Dame. That is rank sophistry at its best, or worst. Tradition at Notre Dame should flourish and enable students to grow. Changes which students of today advocate are not attacks on the past. They are a recognition that a living institution must change if it is to grow and prosper.

Meaningful change will come about, however, only when everyone involved in this community decides that this is indeed a community. We must touch each other as individuals, not overpower one another as institutions. We all have inherent powers, the administration, faculty, students, and alumni; and we have all used our powers in unfortunate ways. Instead of the wise and selective use of power, each group has selfishly fought for its own ends. Thus, rather than interacting as equals, we have sought to overpower. The touch is lost; the handshake is an invitation to wrestle. Notre Dame needs the help of everyone if this place is to become a vibrant community. We need to communicate rather than conquer, to talk to rather than at or down.

The Student Life Council has already experienced this change of attitude on the part of its tripartite membership. In the first ten years of its existence, the SLC saw nothing but “bloc” votes on most issues. Administration took one side, the students the other. Faculty members were the buffer zone and thus suffered much abuse and their motives were always questioned. However, in the past two years the SLC has undergone a change which has changed the entire posture of the body, and, more importantly, of the individuals that serve on it. Positions taken are no longer administration-faculty or student-faculty; rather, every opinion is actively solicited and considered. We have learned to take others more seriously, ourselves less. The administration under the Vice President for Student Affairs Philip Faccenda is no longer the Council’s adversity, but more often its mentor, its advisor. This new era of openness has caused all of us to redefine our own roles. When this openness is apparent at all levels of our community we will be able to live its spirit and look at our problems with a new zest for life. Until we open up to ourselves and other members of our community, we will be afraid to accept “outsiders” into our community.

The American society has many illusions about Notre Dame and many of us have fostered them. We need no longer be looked upon as a football factory or any other such ill-conceived notions. We have made many uncoordinated first efforts; Cotton Bowl minority scholarships, Father Hesburgh’s activities, etc. We must, however, decide if that is to be our course, chart it, and follow it. If we do so, Notre Dame will be a living tradition fearless of social intercourse, because of a knowledge and truthfulness to itself. We can become a Christian community which not only accepts diversity but thrives on it.

This can only come about when we acknowledge our present uniqueness and our need for future diversity. Open communication can accomplish this, if it occurs on all levels of the Nore Dame community. Alumni visits on football weekends are not enough because the frivolity of the moment obscures thoughtful observation. Universal Notre Dame nights are only slightly better, because they once again promote a hard sell, where problems are glossed over. These approaches serve to prolong the illusion because they delay face-to-face communication. They are fleeting cursory glimpses of the institution, the tradition, rather than the people which comprise Notre Dame.

It is in the best interest of Notre Dame that its constituent groups cease to be adversaries. We are often at odds because we are ignorant of each other. We have been told that we are all members of the Notre Dame community — I submit that until we learn to talk to each other, to accept each other’s differences, to refrain from power plays, we will be “one in Notre Dame’s spirit” by circumstance rather than choice.