“The process is magical,” says Kiva Ford, who makes a living converting silica into liquid and then into exquisitely crafted glass forms — some pragmatically useful, and others valued for their artistic quality and on exhibit in museums and galleries.

Professionally, the 43-year-old glassblower fashions the exactingly precise, demandingly functional and elegantly designed glassware required in labs throughout campus. Working with researchers performing many, diverse investigations, he builds to order — based on need, conversations, visions, explanations, diagrams sketched onto a whiteboard, trial and error, and his own keen eye and profuse skills.

In his workshop in a first-floor corner of the Radiation Laboratory, Ford does what he dreamed of doing as a boy: he makes a living making things. The New Jersey native had a close childhood friend who was homeschooled and whose family members were jugglers, artists and craftsmen. “As a kid,” he says, “I liked making stuff. That’s something natural to humans. That’s how I wanted to make a living.” The friend and his family were into woodworking and ceramics.

Young Kiva wanted to find his own way. “I didn’t want to copy my friend,” he recalls. “I wanted to do what he does not do.”

At a county fair, Ford was enthralled by the artisans — the blacksmith forging nails, women weaving fabric on a loom and a glassblower shaping liquid glass into lustrous objects. A nearby community college offered one of the rare degree programs in scientific glass technology. “I fell in love with the process,” he says. “I’ve been working full time since I was 20.”

Early on, he was one of two glassblowers at a pharmaceutical company that employed 5,000 researchers and enough glassware to staff 10 to 12 glass washers. “Tons of glass,” he recalls, “boxes of stuff that went into the dumpster when the company shut down,” putting people out of work, including Ford who had invested 10 years there.

He took the next logical step. He landed at the juggler house at the Philadelphia School of the Circus Arts.

Because his childhood friend’s family also formed a troupe of jugglers, Ford picked up that skill, too. He had been juggling professionally since he was 15. He still performs, often riding a unicycle. But fate soon intervened, as it sometimes does for the talented and industrious. A fellow member of the glassblower’s society, aware of Ford’s prowess, asked him to take his place during a medical leave from Princeton University’s glass shop.

“That was an ideal job,” Ford recalls, “because of the variety of the work.” It meant dealing with smaller, more intricate pieces than he had at the pharmaceutical plant. It was also ideal preparation when the opportunity at Notre Dame presented itself. Working near the center of campus, he fashions a wildly diverse family of sometimes elaborate, fastidiously precise and elegantly crafted apparati for scientific investigations.

Even as a novice, Ford saw the magic in glassblowing, turning silica into liquid into form.

“Plato’s theory of forms resonated with me and glass,” he says, “that perfect form exists in the ether, and we’re here to make copies of perfect form.”

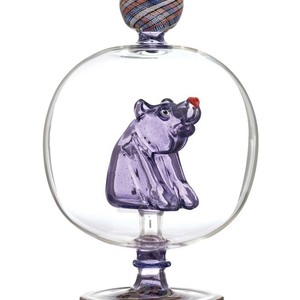

While working in his campus workshop by day, Ford devotes himself to art in his home studio as he can. “The appeal of the artwork,” he explains, “is that you exercise your brain differently — rigid specifications versus no limits. Sartre said something like ‘man is condemned to be free,’ and that’s what can make it scary and intimidating. When I am making a piece, I think, What am I doing? You get these ideas and they start haunting you, they won’t leave you alone, they follow you like a ghost that wants to be made. The glassware is only the vessel.”

The dual endeavors also enable him to experience and express different aspects of this nature.

“It’s crazy how you get attached to your equipment,” Ford says. “It’s like your equipment becomes your friend.” This is partly due to the solitary nature of the work. “There’s so much going on in the world, you just want some peace, to be alone. But then you realize how dependent you are on people. But I also just really enjoy solitude.

“When you’re really in your craft, you’re somewhere else,” he says. “The whole creative project becomes more of a meditation, making what it wants you to make.” Sometimes, he adds, “You wonder, Where did that come from?”

Fords’s handiwork appears all over campus. His artwork can be found online, in galleries, homes, museums and aboard a French cruise ship.

Kerry Temple is editor of this magazine.