One hour and 280 miles separated two of the more dramatic moments in our nation’s higher education history.

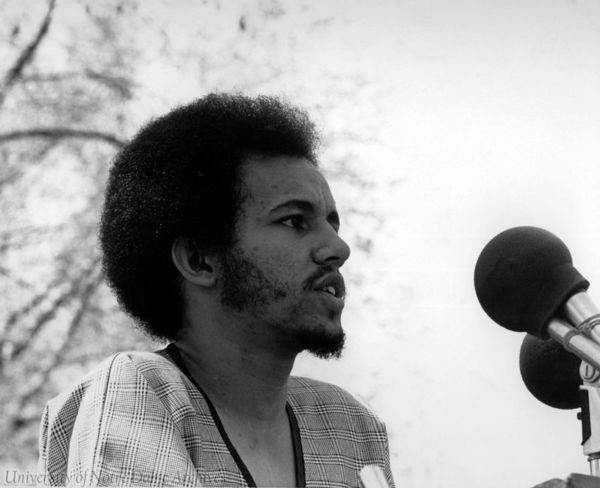

Shortly after 1:30 p.m. on May 4, 1970, David Krashna ’71 took the stage near the flagpole on Notre Dame’s South Quad and looked over the gathering of 1,000 students as the flag fluttered on that breezy, 66-degree afternoon. “Stop, look and listen, and absolutely say ‘Stop’ to the education we are getting at this time,” said the University’s first black student body president, calling for a student strike in response to President Richard Nixon’s nationally televised speech four days earlier.

As Krashna spoke, he could not have known of the tragedy that had just unfolded at Kent State University in Ohio. Thirteen unarmed Kent State students were gunned down by Ohio National Guard troops as some 2,000 students chanted, “1, 2, 3, 4, we don’t want your f---ing war!” Joe Skvarenina, then a 23-year-old Kent State junior, stood 100 feet from the guardsmen near the campus slope known as Blanket Hill as the shooting began. Jeffrey Miller, 20, died instantly, shot through the mouth; Allison Krause, 19, died from a bullet to the chest; William Schroeder, 19, died during surgery to repair a chest wound; and Sandra Scheuer, 20, died within minutes of being struck in the neck by a .30-caliber bullet. Nine other students were wounded, one paralyzed for life.In that address, Nixon had told the nation, “In cooperation with the armed forces of South Vietnam, attacks are being launched this week to clean out major enemy sanctuaries on the Cambodian-Vietnam border.” The president had claimed this was “not an invasion,” but he had fooled no one.

“The shootings were the culmination of four days of intensifying violence that had begun on May 1,” says Skvarenina, who was a student assistant in the school’s Community Relations Office. “The administration had no interest in dialogue with the students. The dean of students sent out a posse to follow activists around campus.”

Only days before, Skvarenina had watched student protesters throw Molotov cocktails at the ROTC building. Protesters then slashed fire hoses and threw bricks and rocks at the firefighters as they battled the blaze. The National Guard, called in by Ohio Governor James Rhodes, arrived as the building was burning and arrested several students, a few of whom suffered minor bayonet wounds. “We’re going to use every part of the law enforcement agencies of Ohio to drive them out of Kent,” Rhodes declared on Sunday, May 3. “We are going to eradicate the problem.”

Instead of eliminating the problem, though, Rhodes and Kent State officials stoked a fire that erupted just after noon on May 4, when a booming G-sharp from the campus’ landmark Victory Bell called students to the university commons. There, advancing Guard troops soon pushed the protesters over Blanket Hill and around behind a couple of campus buildings. At 12:24 p.m., amidst the confusion and having never before faced an angry crowd, the Guard opened fire. An estimated 67 rifle and pistol rounds rang out in 13 seconds.

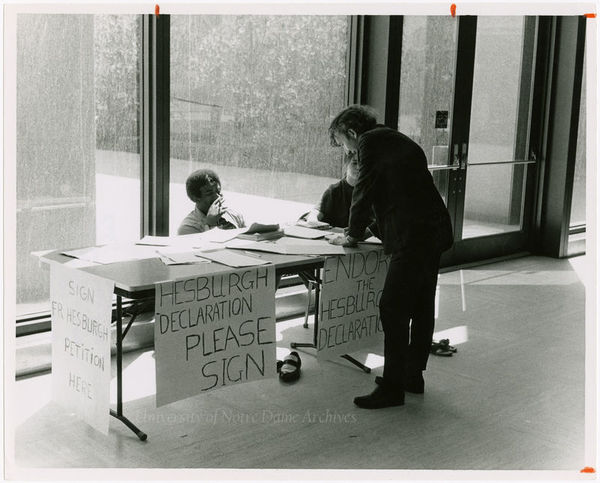

An hour later, Notre Dame’s president, Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, CSC, took the stage on South Quad to address the planned campus rally, counseling reason and caution. Hesburgh agreed the war was immoral, adding, “Moral righteousness is more important than empty victory.” He presented a statement calling on the U.S. to withdraw from Southeast Asia, repatriate all prisoners of war, rebuild a better society in the region and recommit to justice and peace in America, saying he would sign it and encouraging others to sign it before he sent it to Nixon. Hesburgh also tried to preempt Krashna’s call for a strike: “Striking classes, as some universities are doing, in the sense of cutting off your education, is the worst thing you could do at this time,” he said, “since your education and your growth in competence are what the world needs most, if the leadership of the future is going to be better than the leadership of the past and present.”

“I had made up my mind,” recalls Krashna. “We were going to strike. But I was going to respect everyone.” Krashna had just taken office a few weeks before and was still feeling his way in his new leadership role. It was important to him that in addition to protesting the war, issues such as sexism, racism and militarism be debated as well. “Frankly I took it one day at a time,” he says. “It was like, ‘Let’s see how things roll out.’”

That evening, Krashna was summoned to Hesburgh’s office. “It was tense,” he says. “Father Hesburgh and I had some stern words for each other. At one point Hesburgh said, ‘David, when is this going to end?’ I said, ‘I don’t know, Father.’” Despite a tough meeting, Hesburgh and Krashna agreed to keep communications open. That commitment in itself, by two strong-willed men, may have kept Notre Dame from becoming another Kent State.

Hesburgh told the faculty to “underadminister, have discussions, lend your presence,” says Rev. David Burrell, CSC, ’54, then a young professor of philosophy. Burrell, who had emerged as a prominent anti-war voice even before the May 4 rally, cites fellow Holy Cross priests Ernest Bartell ’53, John Gerber ’53, ’63M.A. and Charles Sheedy ’33 as “co-conspirators.” He explains, “The presence of an older person who was a priest and an academic gave students the courage to articulate their beliefs. I agreed with them. They were being sent off to a war that I had determined was immoral. America had stepped into the shoes of a colonial conqueror.”

Divided on strike, united in spirit

At the time, many faculty and students supported U.S. policy in Southeast Asia. Others had no strong views, but an increasing number of faculty and students opposed the lingering war and wanted the U.S. to pull out. Nixon’s “incursion” into Cambodia and decision to extend the fighting beyond Vietnam greatly expanded the movement, with many in the mainstream joining the anti-war left.

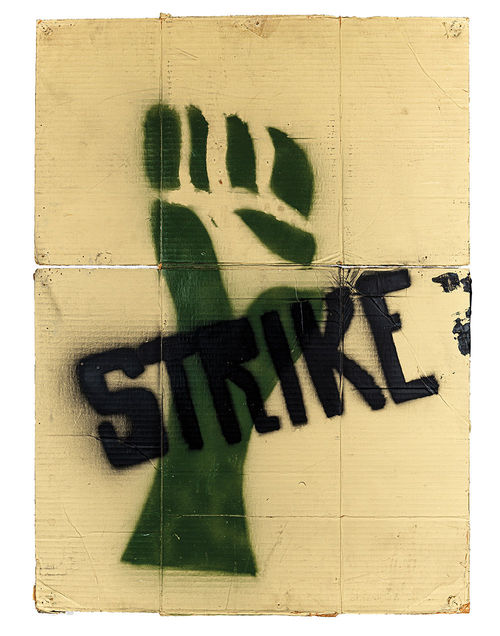

Still, in May 1970 not all administrators were feeling or speaking charitably about the strike. Father James Burtchaell, CSC, ’56, the assistant rector of Dillon Hall, member of the theology faculty and eventual University provost, accused student leaders of striking as a PR stunt, sarcastically asking if they would also be willing to cancel the senior dance and a concert scheduled for May 8. Father James Riehle, CSC, ’49, ’78M.S., dean of students, said the strike would not be peaceful, citing students he had seen running through O’Shaughnessy Hall and yelling “Strike! Strike!” as they tried to interrupt Gerhart Niemeyer’s political science class. Niemeyer, who had lived through the rise of Hitler, compared the strike leaders and their clenched-fist posters to the Nazis and their propaganda.

Most campus organizations endorsed the strike that day. The Student Union shut down normal operations to become “strike central” for student leaders. The Student Life Council, a consultative body of students, faculty and administrators, endorsed Hesburgh’s statement and asked that no student be penalized for striking. John Houck, ’53, ’55J.D., a business professor, suggested one day of marches in conjunction with liturgical services. Ultimately, the council endorsed a two-day strike with “teach-ins” and liturgical services or Masses. They chose a “strike committee” composed of Krashna, student body vice president Mark Winings ’71 and University General Counsel Phil Faccenda ’52. Opponents mocked the “scheduled strike” and its planned ending for not being spontaneous.

A leading driver of the anti-war movement was the implementation on December 1, 1969, of the first military draft lottery since World War II. For young men of this era, the war was not a theoretical concept or foreign policy issue. Bill Miller ’70 was a Notre Dame senior from San Francisco and a deeply committed anti-war activist. He and others counseled fellow students on their options, setting up shop on the first floor of the library. “Guys would line up out the door,” he recalls. “We discussed each option with them: Go to Canada. Petition for CO — conscientious objector — status. Join the National Guard or Reserve. Comply with the draft. Or refuse to comply and go to prison.”

For Miller, the draft was personal as well as political. “I gathered in Dillon Hall that December evening with my roommates and hallmates to listen to the draft on the radio.” Birth dates were pulled in a lottery and assigned a number, with young men called up in the order their birthdays were picked until an annual quota of draftees was reached. A lottery number in the top 125 increased one’s likelihood of getting drafted. “I was lucky,” says Miller. “Number 268. But my roommate got 25, and a friend got 10. There were guys crying and throwing up. It was one of the tensest nights of my life.”

Miller attended every scheduled protest rally during the strike. “I really believe that the reason Notre Dame did not go the way of Yale or Kent State was that every protest rally was accompanied by a Mass. I think the Masses helped channel our thoughts toward peaceful means,” he says. “We were standing upon a foundation of morality and ethics that was built before we arrived on campus as students.”

Father Burrell, who celebrated many of the Masses, agrees the Catholic foundation united the campus. “We had a liturgy at Notre Dame,” he says, “and the Gospel guided us.”

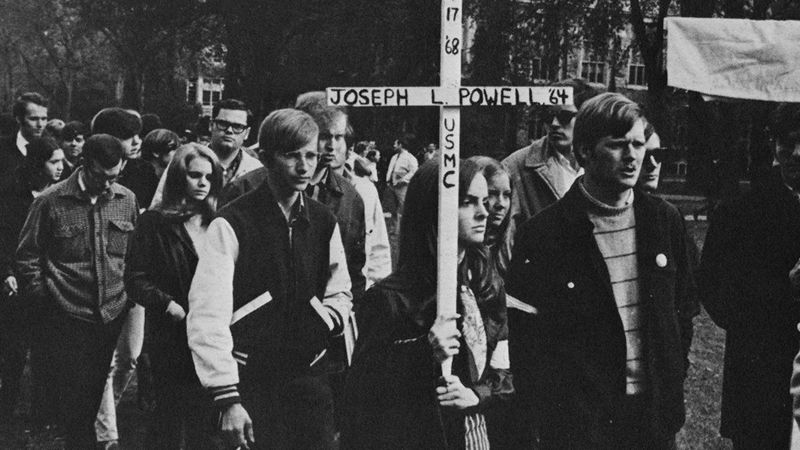

The roots of protest

Stirrings of anti-war sentiment had emerged at Notre Dame in the mid-1960s as military action in Vietnam accelerated. Fred Dedrick ’70, the son of a widow with four children on Staten Island, needed the financial aid of his Air Force ROTC scholarship, and he wanted to be a pilot. By 1968, though, like many other students, he felt he could no longer support the military. He quit the program and would become one of the most active anti-war student leaders on campus.

In November 1969, Dedrick was in the Main Building as the “Notre Dame Ten” attempted to block the CIA and Dow Chemical Company from conducting recruiting interviews at the Placement Bureau. In favor of the protest but wary of the bad publicity that blocking access to the interview rooms might bring, Dedrick found himself trying to break up a shoving match between two students on opposite sides of the issue. Father Riehle soon confronted the protesters and began collecting student ID cards. St. Joseph County police officers arrested one student as he left the building and tried to engage the officers in a debate. Ultimately, 10 students were suspended for violating Hesburgh’s famed “15-minute rule,” which gave students 15 minutes to disperse once ordered to do so.

Dedrick, who also had his ID confiscated, was not disciplined, but later two deputies delivered a subpoena to his room in Morrissey Hall. The University eventually won a permanent injunction against him that, to this day, bars him from blocking access to the defunct Placement Bureau or any other official University office. “The injunction is still one of my proudest moments,” he says.

These were turbulent times. The day after Nixon announced the advance into Cambodia, about 200 Notre Dame students converged on the Center for Continuing Education on Notre Dame Avenue bent on disrupting the Board of Trustees meeting. Issues other than war and peace were on their minds. The students were demanding a greater effort in recruiting minority students, more financial aid for African American students and coeducation. Notre Dame had slightly more than 100 black students at the time and, according to protest leaders, their dropout rate was disproportionately high.

Trustees Thomas Carney ’37 and Bayard Rustin, Notre Dame’s first black trustee, attending his first board meeting, agreed to meet with the student protesters. As a national civil rights leader who helped organize the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Rustin was especially sympathetic to their causes. Dedrick remembers jumping on stage to debate the pair on a point about coeducation. All three were shouted down by angry students.

Campus security soon escorted Carney and Rustin to the Morris Inn, then through the tunnel under Notre Dame Avenue and back to the center where they rejoined the trustees meeting. There some three dozen students went door to door screaming and banging on walls until they found the meeting. While they did not gain access to the room, the trustees adjourned because of the noise.

The march on Howard Park

After the South Quad rally, the campus was boiling with emotion and idealism. The May 5 edition of The Observer dedicated its entire front page to the local story, leading with the dramatic headline, “Krashna: Strike Now,” and relegating the UPI story on the Kent State shootings to page 6.

Krashna and other strike leaders organized the strike’s first official rally on May 5 as well as the “Communiversity,” a series of teach-ins on the Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s campuses that would discuss the war, ROTC, racism and sexism. Taking the advice of the Student Life Council, Father John Walsh, CSC, ’45, ’50M.A., vice president for academic affairs, suspended classes for two days. The Observer opined that it could support the strike insofar as it “resolves the role of the student and the academic community with the war.”

At the Fieldhouse rally on Tuesday, May 5, Krashna announced that, although he had initially supported a limited, two-day strike, he now opened the door to an extended strike. More dramatically, he called for a march to Howard Park in South Bend and, seeking support for Father Hesburgh’s statement, authorized a student campaign to distribute leaflets to South Bend factories and high schools and to canvass homes in St. Joseph County.

Students were also invited to turn in their draft cards to the Scholastic at the Student Union office in LaFortune in a public defiance of the draft.

Some 3,000 protesters marched from campus toward South Bend’s oldest city park, located across the St. Joseph River from downtown. “The citizens were not impressed by long-haired kids with anti-war signs,” Miller recalls. “I had long hair, a beard, and I wore a headband across my forehead. I looked like a stereotypical hippie.” At one point, as marchers chanted slogans, Miller was pelted with eggs and tomatoes and spat upon. “I turned the other cheek,” he says.

The march on Howard Park was successful for its visual impact, but even student leaders were disappointed in the speeches and the lack of concrete proposals for action to end the war. However, one speaker held everyone’s attention — a witness to the Kent State shootings who had seen her close friend Jeffrey Miller die. “His face was blown away,” she said.

While protesters in South Bend were hearing firsthand accounts of the Kent State shootings, President Nixon was meeting with six Kent State students determined to tell the president what really happened on Blanket Hill. Nixon, a Quaker, promised the students he would establish a Commission on Campus Unrest, to be charged with looking at all sides of the nationwide standoff.

Emergency strike agenda

After the Howard Park rally, Krashna realized the Notre Dame strike was losing focus, even as 4.5 million students were striking on 500 campuses across the country. In Austin, Texas Rangers were called in to protect the State Capitol from University of Texas students. Illinois’ governor ordered 5,000 National Guard troops to the main campus of the University of Illinois. In Washington, D.C., 14 American University students were injured during a melee with district police. The National Guard was twice called to the campus of the University of Wisconsin in Madison. Governor Ronald Reagan closed all 27 public university and college campuses in California.

In South Bend, Krashna was grappling with potentially violent agents of change. He recalls students coming to him on the evening of May 6 and asking him to lead their attempt to burn down the campus ROTC building. Krashna says he tried to counter their plan by having other “students follow the protesters to dissuade them from doing anything illegal.” Campus security was on alert after having foiled two attempts on May 2 to burn down the ROTC building. Two unlit Molotov cocktails had been thrown against the building, and a small gasoline fire was ignited. Damage was limited to scorched siding.

Krashna had to figure out how to refocus the strike while combating new opposition from campus groups. Rich Hunter ’71, ’77J.D., a former student senator and head of the Young Democrats, launched the Committee for Academic Freedom, a group opposed to the strike and proposing a challenge to Hesburgh’s 15-minute rule by holding inside the Main Building a nonviolent protest of the cancellation of classes.

Both Dedrick and Krashna respected Hunter and agreed with his premise. But they said they still believed denying the rights of a few for the greater good was worth it. “Kids did not get educated for 11 days. That’s what strikes do,” says Dedrick. “If you can’t strike against immorality at a Catholic university, you have to ask yourself, what are your limits?”

The reckoning for strike leaders came May 7 — the deadline for ending the two-day strike — at an “emergency strike agenda” meeting at Stepan Center. Krashna and his enlarged strike committee faced critics on both sides: those who criticized them for being too militant and those who felt they were not militant enough. History professor John Williams wanted the strike to continue until the ROTC program was dislodged from campus. Professor Charles McCarthy ’62, ’63M.A., ’68M.A. and Father Maurice Amen, CSC, ’57, ’63M.A. had met with Hesburgh to persuade him to set aside one dorm as a “sanctuary” for draft resisters, though they received no support. Meanwhile history department chairman Bernard Norling ’49M.A., ’55Ph.D. and other faculty opponents dismissed strikes as self-defeating.

“It was a very difficult meeting,” Dedrick recalls. “There were 20 guys on stage trying to make decisions in real time in front of 3,000 students.” Some opponents of extending the strike pushed to delay any decision until Sunday, May 10, while others wanted to end it right then. At one point, Dedrick turned to the wall-to-wall Stepan crowd and said, “How can we go back to business as usual while the president, with your bodies and with your money, perpetuates murder on a mass scale?” After heated exchanges, including disagreements between Krashna and Dedrick, a vote was taken.“The emergency meeting really tested my relationship with Krashna,” says Dedrick, whose term as student body vice president had recently ended. “Krashna was caught between militants, administrators, faculty of all ideologies and students who just wanted to get grades.” The strike committee offered a proposal: Extend the strike to May 15, support Hesburgh’s statement and establish the Communiversity. The consensus was to put off discussion of racism, sexism and militarism for one week so the strike could refocus on the war.

The tally counted 250 students voting to end the strike, 1,013 to table the matter until Sunday and 1,309 to extend the strike through May 15. The Notre Dame student strike would continue.

Meanwhile, Dedrick led the community canvassing, gathering 21,000 signatures on a petition to endorse Hesburgh’s statement. Signers included students, faculty and staff as well as local residents.

Bill Miller volunteered to distribute leaflets at the South Bend Kaiser-Jeep plant, arriving just as a shift ended. As workers hurried out of the factory gate, Miller and dozens of other students handed out flyers with an anti-war message on one side and a case for the war’s economic harm to blue-collar workers on the other. “Most of the white workers threw the leaflets back in my face, cursed or spit on me,” Miller says. “But every black man said, more or less, ‘Right on. I’m with you, brother.’”

As Miller approached a white cargo van on the passenger side, a man in his 50s rolled down his window. When Miller attempted to give him a leaflet, the man reached between the seats and pulled out a shotgun. Before Miller could react, the shotgun was three inches from his face. “I thought, This is how it is going to end,” he recalls. “The guy must have seen the fear in my face, all 5-foot, 4 3/4 inches of me, because he said, ‘You stupid little f---er,’ put the gun away and rode off. I was shaking. It was so ironic — I almost got killed trying to stop the killing in Southeast Asia.”

Amnesty and the boycott

Debate next shifted to two issues: Should students be excused from missed classes? And should Notre Dame join the National Student Association (NSA) in a nationwide economic boycott meant to show students were willing to use their buying power to force action against the war?

The Observer reported on May 11 that 88 percent of students contacted had signed a petition favoring “academic amnesty.” A meeting of the Academic Council, whose membership consisted of the top University leadership, including Hesburgh and Walsh, was to debate the concept that afternoon.

Krashna supported the NSA manifesto, which called on U.S. college students to withdraw all personal funds from their accounts by July 4 and to boycott consumer items that college students frequently purchased — everything from razors to bicycles to gasoline, from alcohol to Coca-Cola. The goal was to cause a run on the nation’s banks and to deny President Nixon tax revenue with which to prosecute the war. Notre Dame was declared the Midwestern “regional clearinghouse for information” for the boycott, while UCLA and Clark University served those roles for the coasts.

The Academic Council voted to grant students “excused absences” for all classes missed between May 4 and May 11. They declined to use the term “academic amnesty,” but students, particularly those set for graduation, were appreciative. The amnesty was one more example of Hesburgh’s deft handling of the student body. Whenever he could be empathetic with the students’ cause, without violating University principles, Hesburgh gave ground. Father Riehle, who two weeks earlier had been adamant that the strike would not be peaceful, even changed his tune. “I’m quite happy with the way the strike has been going,” he said at the time.

The strike extension did not dissipate debate on its impact or legitimacy. The Alumni Senate and Alumni Board, in a joint statement, declined to endorse Hesburgh’s statement on the grounds that they were not qualified to speak on behalf of the alumni. Freshman Dennis Wall ’73, in an Observer op-ed piece, wrote, “The strike: a massive blow for peace? Pardon my guffaw. It is more like the prostitution of a great and justifiable ideal.” Kent State and the strike had become the issues, Wall complained, in place of Vietnam and Cambodia.

In contrast to the civility of Notre Dame’s strike, violence continued on campuses nationwide. In Columbia, South Carolina, National Guard troops tear-gassed a mob that damaged university offices. Ohio University students firebombed the school’s cafeteria, and fires set by Illinois Wesleyan students caused $100,000 in damage (almost $700,000 in 2019 dollars). In Mississippi, a Jackson State student and a high school student were killed by shotgun rounds fired by city police. Twelve others were wounded. No one was ever held accountable for the shootings.

Kent State was closed and students were sent home. Joe Skvarenina returned to his family’s farm 60 miles from campus, watched television and took tests the university had mailed him. He also listened to his father who, according to Skvarenina, had said, “They should have shot them all.”

The mood among registered voters nationwide mirrored the division and angst displayed on college campuses. A Sindlinger poll taken May 9-12, 1970, reported that a third of registered voters agreed with Nixon’s Cambodia policy, 23 percent disagreed with it, and 45 percent had “no opinion” or “refused to answer.” For nearly half of all Americans, Nixon and Cambodia seemed too hot to touch.

Strike in limbo

At Notre Dame, the strike plateaued and reached what Krashna called a “state of reflection” as the end of the semester neared. In an op-ed column published in The Observer on May 15, he characterized the strike as “in a state of transition. The emotion and elan of the past week has subsided, and with the recent Academic Council decision, we are in a state of limbo.”

In the moment, Krashna focused on what he thought the strike had accomplished. “Because we were in a state of turmoil both nationally and locally,” he wrote, “I saw the need to say, ‘Stop. Let’s see where we are.’ To a large extent, we’ve done this already — for probably the first time at Notre Dame. Naturally, the war issue took precedence, but subsidiary issues like racism, sexism and militarism, have also been examined.”

He also believed the ideals of the strikers should continue. “The strike should take on a new light. Hopefully students will become involved in canvassing and the Communiversity,” he continued. “This work must go on. . . . I sincerely believe that because of the deep moral questioning on the part of many individuals during those days, Notre Dame can only become a better community for it.”

Five days later, in a campus referendum, students endorsed the McGovern-Hatfield bill, which would have imposed a date of December 31, 1970, for a complete cutoff of funds to prosecute the war in Southeast Asia. The lower-turnout, 1,446 to 472 vote (representing “roughly one-third” of the student body, The Observer reported) may have been the best indicator that students were ready to move on to graduation and summer jobs.

Was it worth it?

While many Notre Dame students continued to actively oppose the war, the University resumed normal operations in the fall of 1970 with little residual effect. Not so for Kent State. In September, Nixon’s Commission on Campus Unrest reported that the Kent State shootings had been “unjustified.” Later that year, 24 Kent State students and one faculty member were indicted by a grand jury on various charges related to the burning of the ROTC building and the events of May 4 — all charges were dismissed by December 1971. Then, in 1974, a federal judge finally dismissed all charges against the guardsmen. Civil suits followed against Rhodes, Kent State’s president, Robert White, and the guardsmen. These were eventually settled for a payment of $675,000.

Joe Skvarenina testified before the Ohio state government panel tasked with investigating the shootings at Kent State. He worked briefly for Nixon’s reelection, then resigned. He retired after a career as a development director for the Lutheran Church and served on the city council of Greenfield, Indiana. “I question more. I question everything,” he says today, summarizing the impact of his experiences 50 years ago.

No violence occurred at Notre Dame, perhaps because student action was informed by Christian values respecting both divergent opinions and authority. Above all, it respected life.

Still, the lessons of May 1970 resonate as clearly today as they did 50 years ago, when campuses were caught up in the throes of protest colored by the fear of losing more young Americans to what many thought was a senseless war.

Fred Dedrick, now president and CEO of the National Fund for Workforce Solutions, in Washington, D.C., says the strike “was a statement about what we should be as a nation. We made a tiny contribution to the national effort.”

“Look at the Notre Dame student body today,” says Krashna, now a California judge and University of California, Berkeley, law professor. “More than 80 percent are involved in community issues. The strike may not have started Notre Dame on the path to moral activism, but it sure helped.”

The strike “moved along the inquiry,” says Father Burrell, now a professor emeritus of theology and philosophy. “You had to upset people’s daily routines. We did that.”

“I did not know it when I volunteered,” says Bill Miller, retired after a 43-year career as an educator and headmaster at California private academies, “but I risked my life to stop the killing. Maybe someone is alive because I stepped forward.”

By that May when the students went on strike, more than 50 Notre Dame alumni had died serving in the armed forces during the war. According to a study by South Bend native and Vietnam vet Darrell Katovsich (PDF), 12 more would die after the strike, including Army 1st Lt. Stephen E. Shields, a 1st Cavalry Cobra helicopter pilot from Clinton, Maryland, and the only member of the Class of 1970 not to return home. Shields crash-landed his Cobra under heavy fire in Binh Long Province on June 20, 1972. He escaped into a bomb crater but was killed in a firefight with North Vietnamese soldiers. Shields was posthumously awarded the Silver Star.

Michael Murphy is the author of The Kimberlins Go to War: A Union Family in Copperhead Country (Indiana Historical Society Press, 2016).