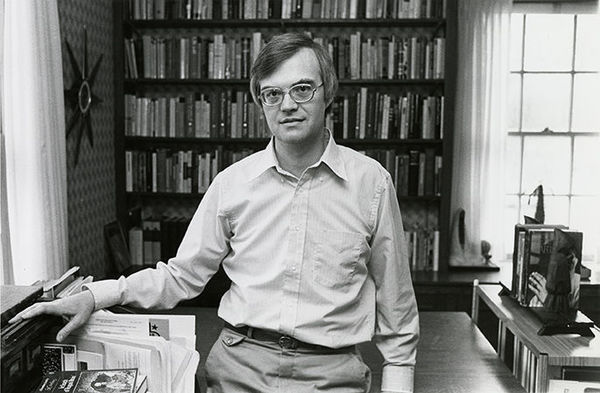

Donald P. Kommers was a professor of political science, a nationally recognized expert in constitutional studies and an erudite scholar whose writings ranged widely and spoke wisely. He was a collegial, cheerful colleague with a warm sense of humor. Born in 1932, he was raised in the small Wisconsin farming town of Stockbridge, living in the back of his father’s grocery store. He worked the fields through long summer days and at his father’s store until heading to boarding school in nearby De Pere at age 13. There, at St. Norbert High School, he discovered the life of the mind and Thomas Merton’s Seven Storey Mountain, an influence he mentioned throughout his life. He also played high school football and hockey and took up boxing — until he knocked out a classmate in the first round of one of his first fights. He never boxed again.

Photo: University of Notre Dame

Photo: University of Notre Dame

Kommers joined Notre Dame’s Department of Political Science in 1963, after serving in the U.S. Marines and earning a doctorate from the University of Wisconsin. His field was constitutional studies, and over a span of 40 years thousands of undergraduates took his popular course in American constitutional law. As the Joseph and Elizabeth Robbie Chair in Political Science, Kommers wrote more than 100 major articles and 10 books on constitutional law, leading a revival of scholarly interest in the field and gaining international renown for his studies of comparative constitutionalism. He also wrote essays for popular magazines and penned book reviews as a regular contributor to America, a Catholic periodical.

Kommers found a second academic home in the Notre Dame Law School, serving for a time as director of the school’s Center for Civil Rights, as co-director of the Notre Dame Law Center in London and as editor of The Review of Politics for more than a decade. But it was his work in comparative constitutional studies, most notably on constitutionalism in Germany, that was most impactful and celebrated. He received that country’s Distinguished Service Cross as well as prestigious honors from its Alexander von Humboldt Foundation and Max Planck Society. When Germany’s Heidelberg University awarded the legal scholar an honorary degree in 1998, it was only the fourth such honor conferred on an American since World War II.

Kommers was also known as a competitive squash player and a bike rider. He learned to ski in his 40s, entertained his wife, Nancy, and their children by imitating Monty Python’s “ministry of silly walks,” and, according to his son, Theodore Kommers ’88, ’92J.D., “knew that love and family are everything.”

“He considered scholarship the highest calling,” Ted Kommers said. “He wrote that the liberal arts and Catholicism together underscore the organic unity of reason and faith, which seek to discover and espouse the truth. Also that they provide an appreciation of life’s religious dimension, a respect for transcendental values, a quiet confidence in the compatibility of faith and reason, and the capacity to distinguish truth from falsehood, right from wrong, good from bad, and the permanent from the ephemeral. In short, moral discernment.”

Don Kommers died December 21, 2018, at age 86.

Gary Gutting transcended categories that can be impenetrable borders — between research and teaching within the academic community, between cutting-edge scholarship and the general public, between opposing ideologies.

Photo: University of Notre Dame Archives

Photo: University of Notre Dame Archives

During his 50 years on Notre Dame’s philosophy faculty, Gutting became a leader in his department and his discipline, a model and mentor to undergraduates and graduate students, and a prominent public intellectual as the author of dozens of articles for The New York Times’ philosophical forum, The Stone.

“As an author, Gary functioned as both innovator and instructor, as someone who saw philosophical interest and power where others do not,” his colleague Paul Weithman said. “As a teacher, his willingness to build his lectures around the questions his students submitted by email gave them a remarkable amount of responsibility for their own education, and represented student-centered learning at its best.”

Writing a remembrance in Commonweal, Gutting’s former teaching assistant John Schwenkler ’05M.A., now an associate professor at Florida State, equated his willingness to explore novel teaching techniques with his capacity to write about philosophical ideas in an accessible way.

Disseminating the vanguard of philosophical thought to the widest possible audience became a professional mission. In 2002, Gutting and his wife, Anastasia Friel Gutting, founded Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews. The online, peer-reviewed journal, which features in-depth critiques of contemporary philosophical scholarship, has become one of Notre Dame’s most visited websites.

Beyond the academic community, Gutting used philosophy to engage the polarizing issues of our time in a way that often spurred Times colleague Peter Catapano to ask, “What would Gary do?” when confronted with vexing ideas. Sometimes he would literally ask Gutting himself, invariably leading to an enlightening and inspiring conversation.

For Catapano, Gutting provided an example, often lamented as lost today, of “civility in public discourse, the nobility of purpose in education and the ability to reach across contentious political and ideological divides.

“The most bitter cultural arguments in American intellectual life were comfortable places for Gary — perhaps he saw them as opportunities,” Catapano wrote. “And I believe that he entered them not so much to establish the dominance of his own view — as a believer in God, in humanistic education, or in the promise of the United States — but to help put the debates on sane ground, to level them through reason and friendly engagement, to be a peacemaker and to advance the invaluable work of civil public discourse and argument.”

Gary Gutting died January 18. He was 76.

Joseph Buttigieg taught senior Prathm Juneja how to read. Juneja was kidding about that, but only a little. The idea that Buttigieg served as an intellectual light from the time Juneja stepped into his literature seminar as a freshman — the kind of compliment the emeritus professor of English would have waved away — is no joke. Many students would say the same.

Photo: University of Notre Dame Archives

Photo: University of Notre Dame Archives

Buttigieg, a scholar of modern literature, critical theory and the relationship between politics and culture, served on the Notre Dame faculty since 1980 and directed the Hesburgh-Yusko Scholars Program from its founding in 2010 until his retirement in 2017. As a professor and an administrator, Buttigieg prioritized the education and inspiration of his students above all else.

“He saw in people what they couldn’t see in themselves and then helped them find it,” Juneja wrote in The Observer. His courses conveyed “the magic in history, the power of analysis and the moral lessons in literature.”

A native of the Mediterranean island nation of Malta, Buttigieg was an influential scholar of the works of the Italian philosopher, writer and politician Antonio Gramsci, editing and translating a multivolume critical edition of his Prison Notebooks. Buttigieg also wrote about James Joyce’s aesthetics in A Portrait of the Artist in Different Perspective.

Educated at the University of Malta, London’s Heythrop College and the State University of New York at Binghamton, Buttigieg’s intellectual influence spans continents. His Gramsci scholarship has been translated into Italian, German, Spanish, Portuguese and Japanese. The Maltese education and employment minister Evarist Bartolo remembered him as a mentor. “He was an intellectual and a moral giant imbued with such a sense of humor,” Bartolo told the Times of Malta. “He really was a beacon of hope for all of us those days in the early 1970s. He believed in the values of social justice and democracy and he campaigned against the ‘money can buy you anything’ belief.”

Buttigieg and his wife Anne Montgomery ’91MFA, a Notre Dame faculty member for 29 years, are the parents of South Bend mayor and 2020 U.S. presidential aspirant Pete Buttigieg. In his memoir, Shortest Way Home, the younger Buttigieg describes his father as “a man of the left,” but his political views were secondary to a classroom ethos of exchanging diverse ideas derived from close reading.

“I don’t think he ever really shared his politics, certainly not with us,” Notre Dame English professor Romana Huk ’87Ph.D., a former doctoral student of Buttigieg’s, told The Nation. “But he had a knack for coming into any conversation with good questions, forcing you to rethink positions. He always provoked us into thinking for ourselves.”

Joseph Buttigieg died January 27. He was 71.

After undergoing brain surgery, associate professor of marketing Timothy Gilbride was soon back in his office preparing to teach his next class.

“This was typical Tim,” marketing department chair Shankar Ganesan said. “I was in total admiration and respect for his passion and dedication to students and teaching.”

First diagnosed with colorectal cancer in 2011, Gilbride remained an active and animating presence until his death January 12 at age 52. He joined the Notre Dame faculty in 2004 and collected numerous teaching and research honors, including the Rev. Edmund P. Joyce, CSC, Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching and a place on the 2018 Poets & Quants list of the top 50 undergraduate business professors.

Marketing professor John Sherry remembered Gilbride as “a triple-threat inspiration whose dedication to teaching, research and service helped us build a scholarly community as humane as it is intellectual.”

Gary Knoppers spent a relatively short time at Notre Dame, but he left a legacy in the theology department as a bridge-builder who brought people with different expertise or perspectives “into conversation with each other,” doctoral student Mark Lackowski told The Observer.

Photo: Matt Cashore ’94

Photo: Matt Cashore ’94

Knoppers, who joined Notre Dame’s theology faculty in 2014 after 25 years at Penn State, died of pancreatic cancer December 22. He was 62.

Twice honored for books in Old Testament studies, Knoppers was an expert in the complex political and historical forces that Jews faced in ancient Israel. To his students and colleagues, he was also an example of generosity and good humor. As associate professor of theology Abraham Winitzer described Knoppers in The Observer, he was “a caring and thoughtful person in the realest sense of the words.”