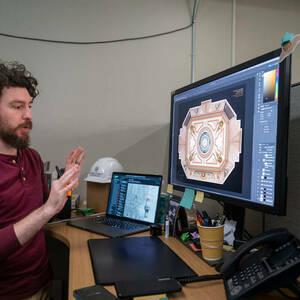

Bryon Roesselet of Conrad Schmitt Studios recreates the 1890s painted decor above the stage in Washington Hall. Photography by Barbara Johnston

Bryon Roesselet of Conrad Schmitt Studios recreates the 1890s painted decor above the stage in Washington Hall. Photography by Barbara Johnston

Editor’s Note: This is the fourth in a Notre Dame Magazine series chronicling the interior renovation of Washington Hall, the University’s 143-year-old campus auditorium.

- The Once and Future Washington Hall

- A Retrospective Renovation

- Setting the Scene

- Questionnaire: Mark Pilkinton

- Dream Job

It was during a long-ago summer working on Touchdown Jesus that Bryon Roesselet first learned of Washington Hall and what it used to look like inside: a lavish display of colorful Victorian-era artwork, all painted over in the 1950s.

Recreating the auditorium’s elaborate and beautiful interior became his dream project. That was 30 years ago.

This summer, Roesselet’s dream became a reality.

He got the call early this year that an interior renovation of Washington Hall would proceed. When he arrived and started gently scraping tiny areas of the walls and ceiling, he found much of the auditorium’s original artwork buried beneath layers of paint.

“I was pretty delighted and thrilled that it was still there and that it was accessible,” says Roesselet, 62, a senior artist and architectural conservator for Conrad Schmitt Studios, the Wisconsin-based architectural arts studio that has worked on projects at Notre Dame since the 1930s.

Roesselet and a team of fellow artisans have been at work since early June inside Washington Hall, the University’s 143-year-old campus auditorium. The major renovation is scheduled to be completed in October.

The project is recreating many of the elaborate details that were added inside the auditorium in 1894 by Luigi Gregori and Louis Rusca, the artists who also decorated the interior of the Main Building and Sacred Heart Basilica.

“On the ceiling, I expected if we were really lucky, there’d be maybe 40 percent of (the 1890s decor) still there, and we’re closer to 80 or 90 percent,” Roesselet says. “Other than the area above the proscenium (which had been plastered over), it was almost all there. It’s terrific.”

Roesselet was born and raised in the Milwaukee area. He attended St. Olaf College, a private school in Northfield, Minnesota. He started as a pre-med/chemistry major, but that didn’t last long. He was studying optical isomers his sophomore year and realized he didn’t enjoy it. “I switched majors the next day, and no one tried to discourage me, which I find astounding,” he says. He graduated in 1984 with a bachelor’s degree in art.

After college, Roesselet worked as an art therapist at a nursing home. Then he got a job as art director for a greenhouse supply company, designing advertising, writing ad copy and creating hand illustrations.

He learned about Conrad Schmitt Studios and it captivated his artistic curiosity. But there was no job opening at the time.

Roesselet started calling the studio once a day to ask about job opportunities. Then he started calling twice a day. Or more. A studio manager eventually took his call.

“He asked me to come in and take a look at the studio,” Roesselet says. He saw the lightboards where elaborate stained-glass windows are restored or created from scratch. The place where religious sculptures are repaired. The studio where paintings and murals are crafted by hand.

He discovered Conrad Schmitt workers had decorated St. John’s Evangelical Lutheran Church in Milwaukee, the church affiliated with the high school he had attended.

Roesselet was hooked.

“I was doubly committed to work there at that point,” he says. “I wanted to be part of that.”

The firm decided to take a chance on Roesselet, although managers didn’t have a precise artistic role in mind for him.

He designed a few art glass windows, although he had no previous training in glass work. Then he was assigned to perform a paint analysis to determine the original finishes of a courtroom as part of the restoration of a historic federal courthouse in Cleveland.

Gradually, he was sent out on projects all across the country, doing site analyses, preparing reports and helping craft plans for renovation or restoration. The jobs include onsite work, long hours on scaffolding that may involve chipping away paint inch by inch, regilding a Golden Dome or hand-painting an interior design.

With each project, Roesselet steeps himself in the history and style of a building’s era.

In 1994, Roesselet — then a young artist for the studio — was assigned to his first project at Notre Dame. The Conrad Schmitt team spent the summer assessing the mosaic pieces of “Word of Life” — aka, Touchdown Jesus — the massive mural on the south face of the Hesburgh Library. The mural was 30 years old and needed some repairs.

The team analyzed the artwork, documenting where pieces of the mosaic were in danger of failing and deciding how to restore it. The team determined most of the caulk holding the pieces together was in danger of failing, so they replaced almost all of it and conserved the integrity of the artwork.

During the summer of the library project, Roesselet visited the campus bookstore and saw a copy of The University of Notre Dame: A Portrait of Its History and Campus, the 1976 campus history by the late professor Thomas J. Schereth ’63.

There, on page 102, was a black-and-white circa 1895 photograph showing the ornately decorated interior of Washington Hall. (That photo became the foundation for this year’s renovation project.)

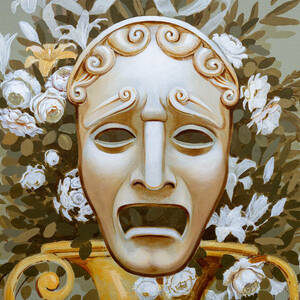

Roesselet says he was immediately taken by the early image of the auditorium, because he’s always been an admirer of trompe l'oeil — a surface painting or design that creates the illusion of a three-dimensional object — which figured prominently in the auditorium’s decor.

“You can create wonderful three-dimensional-looking decoration with just paint. Maybe I like being fooled, because trompe l’oeil means ‘fool the eye,’” Roesselet says. “The amount of trompe l’oeil in that room (visible in the photo) was just spectacular. I was able to go take a look inside the auditorium and it just stuck in my head.”

Roesselet worked for Conrad Schmitt 1990-2006, left and worked for another architectural arts studio, then returned to Conrad Schmitt in 2016. He’s now been with the studio for 24 years.

Early this year, Roesselet started chipping away at the layers of paint inside Washington Hall. That’s when he discovered that most of the luminous 1890s artwork was there underneath. He and his team have been exposing and recreating it during the renovation.

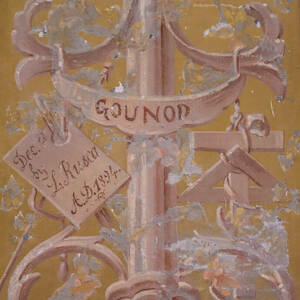

He says the trompe l’oeil work he’s uncovered in Washington Hall (and during an earlier renovation of the Main Building) is among the best he’s seen in his career. Most of it was the work of Louis Rusca, a Swiss-Italian artist — who signed his work in painted script just to the left side of the Washington Hall stage: “Dec(orated) by L. Rusca, A.D. 1894.”

Uncovering that signature came as a big surprise. “Of all the decorative painting projects I’ve ever worked on,” he says, “that’s the first that I’ve ever actually found evidence of the original artist.”

He’s been delighted by the bright and polychromatic paint scheme of the uncovered decor. That was impossible to deduce from the black-and-white photo.

As an artist, Roesselet appreciates what an important symbol Washington Hall was for the University when the auditorium was built in the 1880s and decorated in the 1890s. “It’s a cool part of the history of the campus,” he says, “because it shows the level of commitment to the performing arts back then.”

To Roesselet, the renovated auditorium is a symbol of hope both from the past and for the future. People should view it as a sign “that we should continue to support the arts today, in all their manifestations, both visual and performing.”

When Roesselet first discovered Washington Hall three decades ago, he was a young artist learning the craft from senior artists. Now he’s the veteran artist, a few years from retirement — working alongside, training and encouraging younger staff members.

“The thing that is most important to me in my career at this point,” he says, “is teaching younger folks how to think about these projects and how to accomplish them.”

Margaret Fosmoe is an associate editor of this magazine. Contact her at mfosmoe@nd.edu or @mfosmoe.