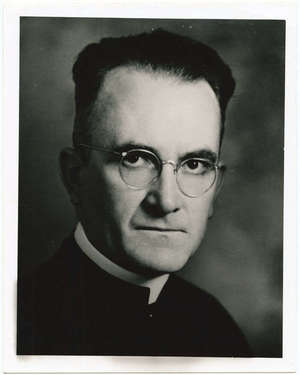

Father Leo R. Ward, CSC, had earned a doctorate, authored two books and written a handful of scholarly articles by 1934, when Father James Burns, CSC, provincial superior for the Congregation of Holy Cross, sent him to Oxford and on to Louvain for two years to study Aristotle and attend lectures by Dorothy Sayers and Jacques Maritain.

The priest, a graduate of the Class of 1923, would later write in My Fifty Years at Notre Dame, “Two problems followed me home across the Atlantic” — challenges still acute today. One he defined as “the problem of human unity.” While in Europe, Ward recognized that individualism disconnected people from one another and from patterns of life that sustained them.

The second he called the “university problem,” explaining that the Church had established universities in the Middle Ages as places where truth was cultivated and offered in service to the world. Those threads of truth, he maintained, shared a singular and universal nature as reflections of an infinite author. According to Ward, the university problem was that the secular university severed those threads from their author and from one another.

In response, Ward dedicated his life to cultivating “holy secularity,” to demonstrating that, as one historian observed, one encounters God not only in devotional ritual but in one’s neighbor, “in all acts of both their individual and communal lives.”

Leo Richard Ward was born in 1893, in Melrose, Iowa, where the seeds of “holy secularity” were planted and defined by the complementary rhythms of work on family farms and worship at St. Patrick Catholic Church. Among his agrarian Irish American brethren, Ward came to believe that “God’s help is nearer than the door, that God is to be — is to be allowed to be — a continual co-presence with us.” Whether plowing or praying, God existed in the secular and sacred details of life.

Ward’s ancestors came to Melrose, later known as Iowa’s “Little Ireland,” in pursuit of what security fertile soil and hard work would afford them. While few recrossed the Atlantic, Ward noted that the spirit of their homeland was woven into the ways they worked to advance the common good.

Following high school, Ward taught for two years and later recounted with dry Irish humor that he then “went off to be a priest because I was not much good on a farm powered by horses and mules, and because there was not much else I could do.” More sincerely, he added that the holy secularity of his youth compelled him to accept that “this divine co-presence, this God-with-us sense, enjoys its highest expectancy in the priesthood.”

Ward, who “had never been twenty miles from home,” arrived on campus in September 1914, and claimed Father Sorin was the first to greet him, peering down from the same pedestal upon which he stands today. Despite his gratitude for his calling, Ward believed his education at Notre Dame and then at Holy Cross College in Washington, D.C., and Catholic University of America existed “outside history” because truth about God was timeless. But how was a young priest to foster holy secularity, to bring that truth to bear on present realities?

Ordained in June 1927, Ward returned to Notre Dame to teach philosophy, committing his life to addressing this very question and doing so in thought and deed. Confusing matters, however, was the fact that Ward’s best friend during those years was the English literature scholar Father Leo L. Ward, CSC. When they were in one another’s company, others distinguished them by calling one Leo L. or “Leo Literature” and the other Leo R. or “Leo Rational.”

Both Wards were renowned teachers, but Leo R., as an extension of his commitment to bring the truth about God to bear on present realities, invested in a teaching style unusual for the day. Instead of lecturing, Ward’s classes were defined by a Socratic give-and-take. Thomas Stritch ’34, a former American studies professor, remembered that Ward “asked hard questions, and invited students to join with him in exploring them.” His exams were not multiple choice, fill-in-the-blank, or even short answer. Instead, they were lists of propositions, and students were asked “to defend or attack them thoughtfully.”

In Ward’s estimation, students prepared to grapple with hard questions were prepared to cultivate holy secularity wherever God led them. Knowing God only called a portion of them to the priesthood, Ward advocated for a greater role for the laity prior to Vatican II. In some circles on campus, he even came to be known as the “layman’s priest” because of his propensity to lobby on behalf of laypeople’s “interests and work and needs.”

Ward wandered beyond the social and professional circles frequented by his predecessors and peers. He became a welcomed presence in the homes of friends in South Bend and a highly desired bridge partner. He also became a welcomed presence at the meetings of organizations such as the American Philosophical Association (APA). “The Campus Maverick,” as Ward came to be known, was the first professor from Notre Dame to join the APA and for 10 years was the only member who was also a priest.

When Ward joined the APA, the association was heavily influenced by John Dewey’s pragmatism. Dewey felt philosophy needed to engage with the social conditions of any given moment in time. Ward agreed, arguing that “philosophy begins where we are” and that “problems were not set by philosophers, but by events.”

Ward departed from Dewey when it came to the sources a philosopher might bring to bear while addressing questions. Dewey believed both the questions and answers existed inside history. For Ward, holy secularity meant questions may exist inside history, but answers may exist outside of it, present in God’s revelation.

In 1930, Ward formally waded into these debates with the publication of Philosophy of Value: An Essay in Constructive Criticism. Absent any means by which to determine how and what one values, Ward argued Dewey relegated such questions to the arbitrary whims of the individual or, more pointedly, of “primal darkness.” In contrast, Ward believed actions were expressions of value and that “value turns out to be (1) our perfection, and (2) God; since in the long run it is at these that our action is aimed.” This side of heaven, people may never perfectly know how and what to value, but holy secularity was the byproduct of striving to do so.

Secular universities, according to Ward, had errantly pursued knowledge apart from the divine truth that had long guided Catholic universities, too often ignoring truth’s universal nature, whose source was its infinite author. Yet he believed the secular university was not entirely to blame. In his most formal response to the “university problem” he had identified during his studies in Europe, Blueprint for a Catholic University (1949), Ward argued: “The real problem for Catholic schools comes from the fact that they have settled in many matters for the mediocre: merely trying to keep up, not to get behind, not to lapse from being accredited.” Catholic universities had come to view their secular counterparts as standard-bearers worthy of imitation.

Ward believed some secular universities escaped mediocrity but he also believed none was adequate. “Adequacy,” while not a seemingly high bar, for Ward was rooted in an understanding of truth being singular and universal. In an assertion with which Ward would concur, Clark Kerr, the president of the University of California, referred to the secular university as a multiversity.

According to Ward, the Catholic university had the best chance of adequacy, of being a true university. Pursuit of adequacy, according to Ward, was an exercise of holy secularity. Scholars in various fields not only had the responsibility of mining what the author of truth laid in the greatest depths but of relating what they found in those depths to other discoveries. The Catholic university, according to Ward, could do so “more than any other force in the Western world.”

Despite the status of St. John Henry Newman’s The Idea of a University as a “modern classic,” Father Theodore Hesburgh, CSC, Notre Dame’s president from 1952 to 1987, contended Ward’s Blueprint was “much more helpful” in shaping his efforts to “create an ever greater Catholic university.” That university, to the extent it fosters holy secularity, was one Ward would appreciate.

Still, the gap separating finite humanity from truth’s infinite author remains today. Relatedly, the problem of the university which followed Ward home across the Atlantic merits constant attention, although Ward assures us that holy secularity is an all-sufficient source of hope.

When Ward tackled the other problem that had followed him home — human unity — he turned to the values that defined the Melrose of his youth. There, he wrote, “We lived community, and without being aware of this we understood and loved our community; it was like our soul.” Part of what defined that sense of community was that “almost all were Catholics, attending the same church and the same Irish wakes,” with the other part aided “by the pioneers’ need to help one another.” In Ward’s opinion, Melrose was blessed but not unique in its cooperative nature, which existed in many communities. The question for Ward was how people habitually responded to the pressures, often economic, placed upon them.

With street names such as Kilarney, Tipperary, Shamrock and Leprechaun, Melrose compelled Ward to consider whether the cooperative spirit in Ireland might even be more ideal. After landing “in the Irish West” and hearing the “Galway and Mayo brogue,” Ward contended he, in fact, “had come home.” Tales of his wandering Ireland’s hillsides and sitting with its people are found in God in an Irish Kitchen (1939) and All Over God’s Irish Heaven (1964).

The first effort he later described as “a romantic and nostalgic idealization of Erin and its people.” Critics praised the second as a worthy sequel. As narrative windows, Ward hoped his accounts of Ireland would inspire others to consider what virtues define the places they call home.

Today human unity may be the more pressing of Ward’s challenges. Given the plague of COVID-19, the recent wave of racial reckoning and severe social fragmentation, these accelerants to the existing problem seem to have dashed the possibility of disciplined discourse. But here, too, Ward’s holy secularity may be a source of hope. Questions may exist inside history, but holy secularity means that the answers to those questions may exist outside of it.

Todd Ream is professor of higher education at Taylor University. A fellow with the Lumen Research Institute and publisher of Christian Scholar’s Review, he is working on a series of books concerning Father Hesburgh and lives in Greentown, Indiana.