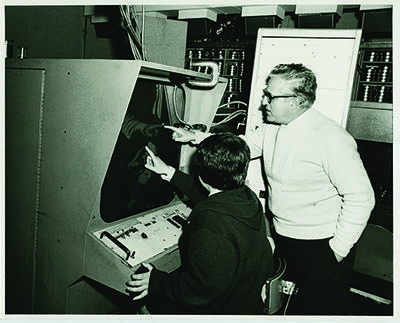

V. Paul Kenney, who died July 18 at age 87, was brought to Notre Dame from the University of Kentucky in 1963 by University President Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, CSC, to start, along with colleague Bill Shephard, its High Energy Research Program. High energy physics explores the fundamental natures of matter and energy, space and time. Kenney — as captivated by subatomic particles as by the stars scattered across a black sky at night — led that program until he stepped down 31 years later. He was the author or co-author of some 170 publications on elementary particle physics. His efforts to track quarks through supercolliders led him to conduct experiments at the world’s foremost accelerator facilities, including Fermilab in Chicago and CERN in Geneva, with multiple research appointments at the Max Planck Institute for Physics in Munich and the Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge University. He also served in the High Energy Physics Division of the U.S. Department of Energy and was an adviser to the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops on energy and society issues.

Colleagues remember Kenney not only for his scientific contributions but also for the leadership, determination and humanity he brought to his research program. Every Monday Kenney’s team met for brown-bag lunches to present and critique their works in progress. Their academic papers were group projects, and the director often put up other faculty for recognition and pushed them forward to speak at professional conferences when it was actually he who had been invited. “Paul was the kind of leader most people would pray to have,” recalls one departmental veteran. “His leadership style was to lead by consensus.”

That culture of collaboration and community made the high energy group “a social as well as a research group,” celebrating birthdays together, eating together (monthly meals hosted by its “foreign foods gourmet club”) and camping together along the shores of Lake Michigan, in Indiana woods and at Colorado’s Rocky Mountain National Park.

But Kenney is also remembered as a tough and loyal administrator who built a stellar program, advancing its scope, its output and its reputation. “He had to work very hard to obtain the resources we needed to do our research,” says a colleague. “We needed money, faculty positions and space in the department — and for each of these things, other people would not get the resources if we got them. He was a very tough infighter and negotiator, and he saved the rest of us from having to do the fighting.”

His widow, Margaret, four children and 13 grandchildren knew Kenney, a native of New York City, as a devotedly loving family man, an actively involved Catholic, historian, teacher, debater and photographer, but not a swashbuckling pirate (despite the reports). The family enjoyed their travels from Big Sur to the Everglades, the outdoors and camping in the “Big Blue Tent,” as well as lakeside gatherings for which Kenney offered cruises on a yellow Sunfish and pitchers of martinis. Throughout his life, his family attested, he “maintained the brass of the Bronx and his blue-collar childhood. Whether he was pushing for your promotion or battling benighted authority, it was clear that when he was with you, your force was mighty.”

Kerry Temple is editor of this magazine.