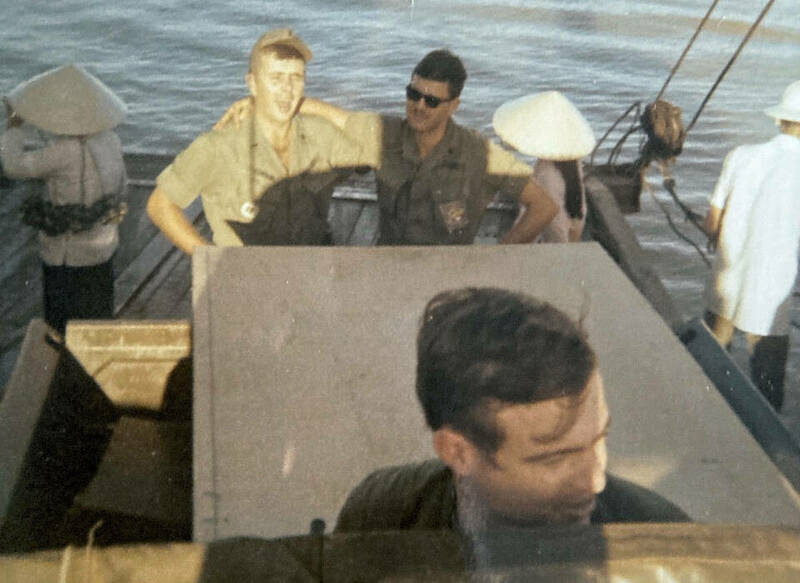

The author, back left, waits for a ferry to cross the Mekong River in 1970. Photos courtesy Tom Condon ’68

The author, back left, waits for a ferry to cross the Mekong River in 1970. Photos courtesy Tom Condon ’68

Last year my daughter asked me if there was anything I’d like for Father’s Day.

“How about a Vietnam Veteran hat?”

She was surprised at the answer, and so was I. After serving in and then studying the Vietnam War I believe it to have been a tragic mistake, a godawful waste of lives, resources and my time.

So why, more than a half-century later, did I feel the need to announce that I took part in it? I wasn’t quite sure.

For openers, the hat rekindled the memories. Set the wayback machine to 1966.

I was an undergraduate at Notre Dame and the military draft was in force. My seriously inept local draft board sent me a draft notice. I wrote back and said au contraire, I have a 2-S student deferment, which is good for four years. I, as I once heard a sports announcer say, am in my second year and only a sophomore. Ah, right you are, they answered, so your date of reporting is extended to the day after you graduate in 1968.

That forced my hand. Though I’d given some thought to the Peace Corps, there was pressure to join the war corps. My father and his friends had marched off the World War II. I played for a baseball team sponsored by the neighborhood American Legion Post. We’d go to the bar for Cokes after games. It was full of WW II vets, the local chapter of the greatest generation, smiling and self-satisfied at having done the great good thing.

Would I let them down by not answering the call myself? Be thought a coward? Bring dishonor on my family?

The Army had a two-year ROTC program, which involved attending a compressed version of basic training at Fort Knox in the summer between the sophomore and junior years. I reluctantly signed up.

My ROTC career would not have suggested a future Grant or Sherman (unless we’re talking about Lou Grant or Allen Sherman). I did not put my whole heart and soul into it, truth be told. Fortuitously, Note Dame’s Army ROTC program was then run by Col. Jack Stephens, a buoyant, feisty and wise man who understood that he had some draft-induced volunteers under his tutelage for whom the military was not a burning passion. But he figured we’d make decent officers if he could shoehorn us through the program, and so he did, and he was right.

In October of 1969 I stopped at Notre Dame for a football game on my way to Vietnam, and there was my friend and classmate Rocky Bleier ’68, on crutches and weighing about 140 pounds. The football captain in 1967, he’d been badly wounded in Vietnam a couple of months earlier. He would — somehow — drive himself into playing condition and win four Super Bowl rings as a starting halfback for the Pittsburgh Steelers in the 1970s. Amazing what some people can do. And yet, someone said, so much wasted gallantry.

A few days after that visit I was getting off a plane at Bien Hoa airfield. It was close to 100 degrees, and humid. Rockets had struck the field the previous night. I had a hangover from my last night in San Francisco and hadn’t slept in 24 hours. Good morning, Vietnam.

I was assigned to an Army communications unit as a kind of all-purpose lieutenant. I was the pay officer, the supply officer, the transportation officer, even the vector control officer. I didn’t know what that was; it had something to do with killing rats.

A couple of pucker-factor experiences notwithstanding, I was mostly a REMF, a rear echelon mine finder, in the family-friendly version of the acronym. The war dragged on, days passed slowly, each crossed off a short-timer’s calendar. While some units fought fiercely, many others had little to do. Many GIs palliated the boredom with alcohol, drugs or prostitutes. Many GIs contracted the clap.

I recall the huge base camps, airfields, ports and other stuff the Americans built. It was a grand time to be a military contractor, but then, when isn’t it? Tactics got more desperate and bizarre. Destroying villages to save them? Spraying the country with highly toxic herbicides? Bombing triple-canopy jungles? Somebody thought these were good ideas?

One comic moment: After I’d been in Vietnam for five months, my local board drafted me again, sending an official notice ordering me to report to the induction center in New Haven, CT. I chuckled and sent them a letter pointing out that their mission was accomplished, I was already in the Army, drafting me would be redundant, etc. A couple of weeks later I got another form letter, saying that because I was residing in a foreign country other than Canada or Mexico, my date of reporting was extended for 15 days. I could not have made this up.

A few years later I opposed ending the draft; I don’t think national service is a bad thing and believe the burden ought to be shared. But I was happy that they abolished my local draft board. They were giving government bureaucracy a bad name.

Near the end of my one-year tour I was presented with the Bronze Star and Army Commendation medals, both for “meritorious achievement.” I can say without an ounce of false modesty that I did nothing to merit any medals, but they were handing them out willy-nilly, like participation trophies at a Little League banquet. There may be a corollary to Parkinson’s Law here: The number of medals presented is in inverse proportion to how well a war is going.

I endured a bit of hearing loss due to the infamous military oxymoron “friendly fire” but I could still hear the wild cheering when the “freedom bird” cleared Vietnamese air space and headed home. At least eight of my Notre Dame classmates didn’t get to hear the cheering.

While it seems ever so naive in retrospect, it was hard for me to believe back then that the U.S., the good guys who won World War II, could get this so wrong. In the years following my return I read many of the major works about Vietnam and the war: Karnow, Greene, Caputo, Herr, Fitzgerald, Fall, Wolf, Del Vecchio, O’Brien, Viet Thanh Nguyen, Sheehan, Kovic, Hastings and others. I concluded that we had erred egregiously, that the conflict was a ghastly tragedy.

I’m a journalist and made a reporting trip back to Vietnam in 1989, a time when groups of vets were going back for humanitarian missions, such as opening clinics. I went with a group of ex- Marines who had collected maps of minefields — unexploded ordnance was a huge problem — and were bringing them to government officials.

To my great surprise, most of the Vietnamese were happy to see us. I was told the Buddhist mindset is to look ahead and not dwell on the past. Also, they tired of the Russian advisors who came to the country after we left; one fellow called them “Americans without smiles and without dollars.”

The hardest parts were going to a hospital to see children born with horrific birth defects, related to Agent Orange, and visiting the village of My Lai, where an American unit had killed hundreds of civilians; men, women and children, in 1968. The guide was one of two girls — by then young women — who survived by hiding in a pile of dead bodies. My childhood wasn’t like that. I felt shame. Real raw shame. I could not speak for several minutes.

There was a trade embargo with Vietnam in 1989 — we had to fly in from Thailand — and I was asked upon my return to testify before a Congressional committee considering lifting the embargo. I asked the solons to consider the inconsistency: “Twenty years ago it was illegal not to go to Vietnam, now it is illegal to go.” By the way, I added, people from 20 other countries are there opening factories and other businesses.

The embargo was lifted in 1994.

It took courage to go to the war, and it took courage to actively resist it and risk imprisonment. I had friends who left the country, others who became teachers to avoid military service. I never had a problem with the latter, it was de facto national service. Maybe the best thing to come out of the Vietnam War was some good teachers (although I was mildly piqued every year when they got Veterans’ Day off and I had to go to work). I have no respect for those who faked injuries or illnesses, or mutilated themselves, to avoid the draft. At least no one had to go in my place.

We vets weren’t warmly welcomed on our return from Southeast Asia, even by some older veterans — the guys at the Legion bar. Well, hell. We performed as well as they or any other American troops ever had, but in the end could not prop up a series of corrupt and incompetent South Vietnamese governments. I recall a story in which, well after the war ended, a senior American officer met Gen. Võ Nguyên Giáp, the legendary North Vietnamese military leader.

“You know,” said the American, “We never lost a battle to you.”

“That may be true,” Giap answered, “but it is irrelevant.”

So, the hat. One reason I wore it was just to see what the reaction would be. Would someone ask me, as someone did 50 years ago, if I killed any babies. To the contrary, the most common reaction to the hat was: “Thank you for your service.” I even heard this from some teenagers, and tipped my hat to their parents. But it left me a little uneasy; kid, if you only knew what you were thanking me for.

Also, the hat was a way to connect with other veterans, which I like to do. For example, I ran into a fellow Vietnam vet at a food store.

“’67-’68,” he said.

“’69-’70,” I replied.

“I thought it would have been over by then,” he said.

“I wish you’d been right.”

I met a Gulf War vet.

“I think you Vietnam guys had it worse than we did,” he said.

I shrugged, I couldn’t say, it depended. I gave him a thumbs up.

The one thing we the country could have done with the Vietnam War was learn from it. The endless wars of the past three decades suggest we learned very little. We tried hard to forget the Vietnam War and it worked. And so we were condemned to repeat it. Did that bum’s rush out of Afghanistan last summer look vaguely familiar?

So perhaps the hat will remind me to bear witness. We Vietnam vets are now senior citizens. On our way out the door I wish we could leave the country a message: The Vietnam War was a mistake. It sucked. Please don’t let it happen again.

Finally, I should mention that a guy at the farmers’ market saw my hat and gave me a buck off on a loaf of French bread. That was nice of him.

Tom Condon, a retired columnist and chief editorial writer for The Hartford Courant, now writes for The Connecticut Mirror. Find his stories at ctmirror.org.