Agustín Fuentes has spent much of his academic career debunking myths about human nature in ways that non-academic audiences can understand, and this afternoon is no different.

Fuentes at Notre Dame's Museum of Biodiversity. Photo by Matt Cashore '94

Fuentes at Notre Dame's Museum of Biodiversity. Photo by Matt Cashore '94

We’re sitting in his office in Corbett Family Hall, and the anthropology professor, who also serves as Notre Dame’s Rev. Edmund P. Joyce, CSC, Endowed Chair in Anthropology, is counting up the ways people oversimplify what it means to be human.

Far too often, he says, we focus on the worst aspects of human behavior — things like violence, cruelty and tribalism. And we tell ourselves this behavior must result from innate traits that are nature’s unfortunate inheritance to us. But while that belief may square with our intuition, he says, it’s also wrong. Reality is more complex, and ultimately, more hopeful.

“My research, and the research of countless other folks into understanding human biology, human society and human evolution demonstrates that at the core of what makes humans successful is an uncanny and intense capacity to collaborate, to cooperate, and to create,” he says. “Now, that can have horrible outcomes, but often it has very positive outcomes. And we never pay attention to that.”

That said, Fuentes is no Pollyanna. He speaks passionately about rising economic inequality, is appalled by today’s political climate, and would relish the opportunity to debate a public intellectual like Steven Pinker, whose latest work on human progress, he wrote earlier this year, demonstrates “a stunning lack of empathy.” It’s not that the world isn’t at times a cruel and violent place, he says, but it’s a mistake to say that’s because of inborn human traits. Which leads him to myth-busting.

“All these people have all these assumptions, but you can actually go and look at the data,” Fuentes says. “The myths are these simplistic, easy explanations, and it turns out nothing about the human is easy. So I take busting myths as an intellectual contribution to the world. We have data and knowledge inside the University. We try to convey it to students as best we can to inspire them to think, to create, to move forward and change the world, but at the same time we need to move forward to translate outside the academy. And that’s where the myth-busting work is really important.”

Fuentes has taken on cultural myths in a variety of forums, but perhaps most famously in his book Race, Monogamy, and Other Lies They Told You. I am eager to explore these myths further, and he is happy to oblige. We begin with race.

“We know that black, white, Asian, whatever — those are not biological units in humans,” he says. “At the very same time, being black or white or Latino or Asian, for example, in the United States is real. Absolutely real. These are cultural constructs, but they have real implications.

“So in fact, racism — the discrimination against others because of their assigned race in a particular system of power — has huge biological effects. So race is not a biological unit, but racism creates biological differences in races — biological outcomes, health outcomes.” For instance, Fuentes cites the huge disparity between overall infant mortality in the United States and African-American infant mortality.

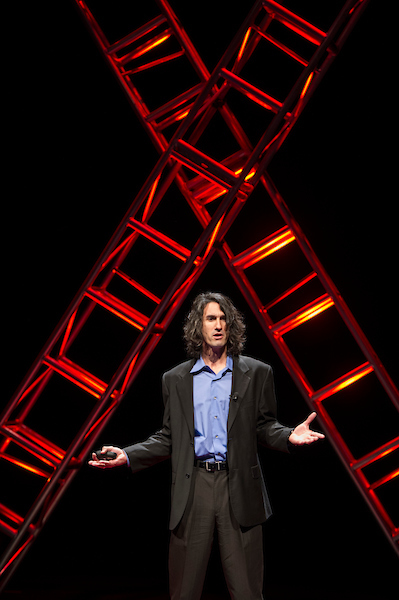

Fuentes giving a TEDxUND talk in 2014. Photo by Barbara Johnston

Fuentes giving a TEDxUND talk in 2014. Photo by Barbara Johnston

But if race is a cultural construct, he says, there’s a hopeful implication: we can do better as a species at combating racist behavior and the social conditions it supports.

“That means that we have the capacity and the possibility of increasing care and compassion in the ways in which we relate to one another,” Fuentes says. “There’s historical evidence for it, and we can do it in the future, but we have to work hard. And right now in the United States it’s probably the hardest it’s ever been.”

Another series of myths revolve around aggression, Fuentes says. People aren’t inherently violent, and men aren’t wired to be sexual aggressors, even if some people act violently, and some men behave in sexually aggressive ways.

“I don’t think we would have made it as a species if that was true. It flies in the face of all the data we have,” he says. “Humans have the incredible capacity for violence and cruelty, but we also have a well-documented and clear biological, cultural, neurobiological, endocrinological capacity for care and compassion. It’s amazing how humans can care.”

Fuentes has also taken on plenty of myths about sex and sexuality. People sometimes say sex is biology and gender is culture, but he notes it’s more complicated than that. He points to tests of brain function. You can’t pick up a brain and tell if it’s male or female, he says, although you can look at brain function and observe some differences between men and women. But here’s where it gets interesting: that’s just from looking at adult brains. In teenagers, Fuentes says, there’s less of a difference in male and female brain function. And if you look at the brain function of male and female six-year-olds? You can’t discern a difference.

“That’s gender,” he says. “And that’s why gender and sex are both biology and culture. It’s the way in which we train our body. Because remember, our bodies, the way we walk, all these kinds of things are accentuated by [the fact that] we are who we grew up with, and by these expectations. And so that stuff is fascinating. . . .we are biocultural critters, and everything about us is an amalgam of that stuff.”

The biology and behavior of human sexuality, Fuentes says, is also an area prone to misunderstanding.

“It turns out that that humans are pretty much quite varied and all over the board — always have been and still are,” he says. “And we’re finding when you try to constrain that in particular ways, you sometimes have problems. Not that anything goes. But a sincere and honest understanding of the normative range of diversity of sexuality in humans is really important information. And if we had that and we could understand that and discuss it openly, we might have a lot fewer problems than we currently do now. And that’s just data. I’m not trying to take a political stance, I’m just saying, ‘what’s out there?’”

Fuentes sees addressing cultural misconceptions and oversimplifications as an ethical obligation, a chance for him to use his position of privilege as a tenured academic to help make the world a better place. Getting past myths should also be part of a classic liberal arts education, he notes, which challenges students to move beyond their preconceptions and think critically.

And if it turns out human nature was a bit more complicated than we thought? Fuentes thinks that means we have more opportunities than we once realized to make things better.

“Why do we keep only talking about the violent, only talking about the cruel, only talking about the differences,” he says, “when we know that cooperation, compassion, and similarities are as — if not more — important?”

Josh Stowe is alumni editor of this magazine.