I am greeted in the entryway by the dogs of the house, friendly rescues Everly and Trastu. Everly’s local, a South Bend townie, wary but willing to give a visitor the benefit of the doubt. Trastu’s moved around the world in his 13 years — Italy, Barcelona, Mallorca, South Bend — and exudes composure in new company.

Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi, the author and Notre Dame writing professor, hustles them off to the kitchen, a situation that Trastu, the cosmopolitan elder, accepts with a grudging equanimity. Everly objects with more urgency, an approach that springs him within a minute or two, and back into the living room he comes, content to share the space. I’m grateful for the hospitality, canine and human, and happy Everly didn’t have to stay holed up on my account.

“Dogs are a big thing for me,” Van der Vliet Oloomi says later, amid a happy reunion after Trastu has been turned loose, too. “They’re my best friends and I love rescuing them.”

This personal infatuation has little to do with her writing, except insofar as nothing in her life can be separated from the compulsive act that has been her emotional respiratory system since she was a teenager, if not before. “It’s kind of like breathing air for me,” she says.

Her literary exhalations have led to a productive and successful “career” — a word that seems not to sit quite right when applied to such an innate and essential undertaking. Writing is who she is, not what she does.

“It was just kind of the state of things. I always was writing,” she says. “I always considered myself and my identity as being deeply entrenched with writing and the career just kind of evolved as a result of that rather than the other way around.”

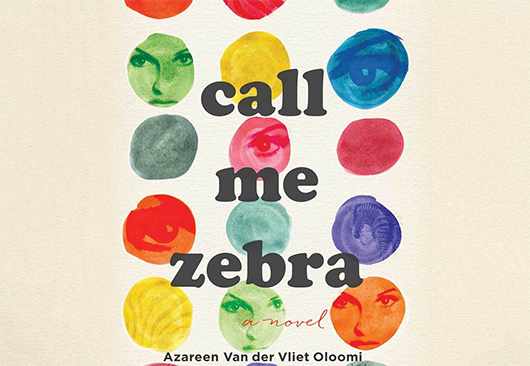

Questions of identity animate her intertwined life and work. In Van der Vliet Oloomi’s second novel, Call Me Zebra, longlisted for the 2019 PEN Open Book Award, the exiled narrator defines herself through literature. Bibi Abbas Abbas Hosseini is the latest in her family’s line of “Autodidacts, Anarchists, Atheists.” Her father instructs her to find protection from the physical and psychic rubble around them through the pages of the world’s great works. Literature, he says, “is the only magnanimous host there is in this decaying world. Seek refuge in it.”

In the Iranian-American author’s own nomadic life, writing has offered a reliable safe harbor, words an armor to shield her on each new shore. She’s lived in New York and Los Angeles, Iran, Dubai, Spain, Italy, Indiana. A question like “Where are you from?” often leaves her at a loss, requiring some level of self-amputation to answer. “I don’t know where I’m from, to be honest,” she says, meaning that laying claim to any single, predominant “home” necessarily leaves out an essential part of herself.

She excavates her way through fragments of place and layers of identity on the page. She’s searching not only for answers about herself, but for “insight into the human condition — a curiosity that is impossible to satisfy,” she said in an interview with the Chicago Review of Books, “and that only leads to the production of more literature.”

Her relentless curiosity and literary production go way back. The happiest years of her childhood, she says, were spent in Iran. Moving at age 7 to the country her mother had left in the early 1980s, she encountered the language she had spoken with her parents in its cultural context.

Farsi on the billboards loomed like an alphabetical spectacle, awakening her to the pliable potential of language, “like a sculptural element or a material that you can manipulate.” She wouldn’t have put it that way as a 7-year-old, but looking back, she sees how the experience widened her eyes and compelled her to begin manipulating those symbols to record the world around her.

“That’s when I started noticing things,” she says, “and writing things down” — a practice she’s hardly ceased since, orienting her life around it from about age 17.

Van der Vliet Oloomi protects and honors her writing process, taking pains to slough off the inhibition that insinuates itself if she’s not in the right frame of mind or feels disconnected from the work because of other obligations. “I’m really interested in the surrealists, so I have some surrealist practices,” she says. “Like I’ll write with my eyes closed or I’ll experiment with hypnosis and go back to writing.”

Those rituals help her “feel more free to be playful and wild and uncensored.” Call Me Zebra — Zebra herself, in particular — possesses that spirit. The New York Times called the book “a tragicomic picaresque whose fervid logic and cerebral whimsy recall the work of Bolaño and Borges.”

With her parents, Zebra flees war-ravaged Iran as a child, the first of many new chapters in a life buffeted by forces beyond her control. After her parents die, she sets out to recreate the path the family followed, a “Grand Tour of Exile.” She renames herself after “an animal striped black-and-white like a prisoner of war . . . that represents ink on paper” and rambles, word-drunk, through the places of her past and the lives of the new acquaintances she encounters.

The places include the physical — New York, Barcelona, Iran — as well as a cartography of the card catalog, the philosophical and literary traditions Van der Vliet Oloomi researched as a Fulbright Scholar in 2010 when she conceived Call Me Zebra. In part because of the inquiry required to tap her protagonist’s inky veins, the book was the better part of seven years in the making. Combining the intellectual allusions with the “propulsive narrative energy” of Zebra’s journey and personality “took a lot of years of me maturing as a writer, too,” she says.

She wrote her first novel, the “stunning psychological thriller” and “surrealist triumph” Fra Keeler, in a comparative blur as a Brown University MFA student and published it in 2012 to acclaim that make the reception of her second no surprise.

The books have similarities, but in the later novel Van der Vliet Oloomi “immeasurably expands her terrain,” the Times review notes in reference to the scope of the book — though the phrase also could mean a deepening of her response to the question, “Where are you from?” Not to someone else’s satisfaction, but to her own.

She feels American, Catalan and Iranian all at once, an answer that doesn’t lend itself to small talk but that opens fertile landscapes for literary exploration.

Jason Kelly is an associate editor of this magazine.