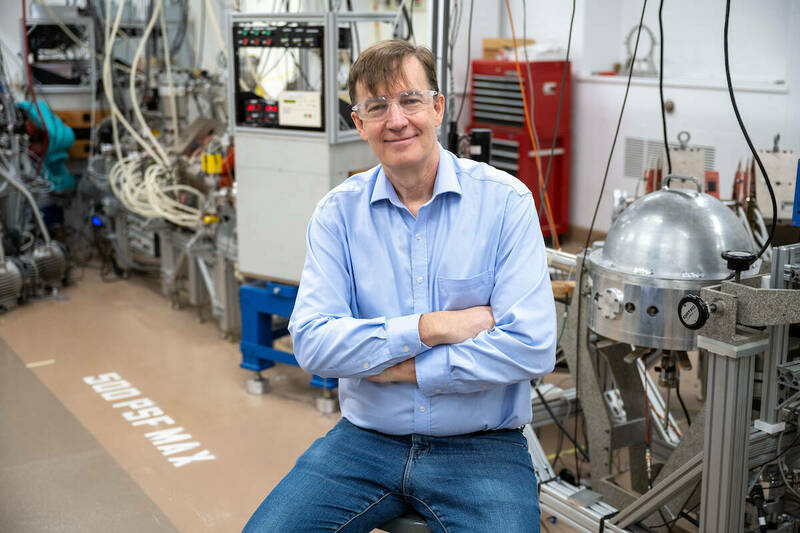

Peaslee: ‘PFAS is probably the worst environmental pollutant that the United States has ever faced.’ Photo by Barbara Johnston

Peaslee: ‘PFAS is probably the worst environmental pollutant that the United States has ever faced.’ Photo by Barbara Johnston

Graham Peaslee spends a lot of time thinking about the chemicals in the clothes we wear, the cosmetics we use and the water we drink.

His research has taught him to be suspicious. In his laboratory, he has found dangerous chemicals in firefighting gear, food wrappers, school uniforms, plastic containers and makeup. Nearly every month, the list of known contaminated products grows.

Peaslee is a nuclear physicist who specializes in the study of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances — known as PFAS. They are a large, complex group of chemicals that have been used in consumer products globally since they were first produced on an industrial scale during World War II-era research to create the first atomic bombs.

Because it is believed that many of these compounds will take more than 1,000 years to degrade, they have become known as “forever chemicals.” To date, according to the National Institutes of Health, more than 9,000 PFAS have been identified.

Exposure to various PFAS has been linked to numerous health issues, including prostate, kidney and testicular cancers, low birth weight, immunotoxicity and thyroid disease. PFAS can migrate, contaminating food and accumulating in human bodies.

“PFAS is probably the worst environmental pollutant that the United States has ever faced. It makes all the rest” — including PCBs and asbestos — “pale in comparison to what the cost of this cleanup will be,” Peaslee says, and it will affect more people than all known pollutants combined. “They will not hold a dime when people are looking back at this in 30 years.”

Peaslee and I are having this conversation outside a campus café. I glance down at my paper coffee cup and wonder about its protective coating.

PFAS are found nearly everywhere, including in groundwater, rainwater, soil, freshwater fish and some types of dental floss. An estimated 97 percent of Americans have some level of the chemicals in their blood, including newborn babies.

Intensive study of these compounds — long considered wonder chemicals because of their myriad commercial uses in products that can resist grease, water and oil — started about eight years ago. While Peaslee focuses on detecting the chemicals’ presence in such products, other Notre Dame researchers are examining ways to mitigate PFAS contamination and whether incineration is a safe means of disposal.

One of Peaslee’s early studies examined textiles and paper using a particle accelerator. The fabric in a certain brand of stain-resistant men’s trousers immediately tested positive for PFAS; the manufacturer no longer uses the chemicals.

Peaslee and his team also tested more than 400 samples of fast-food packaging treated to make the paper grease and stain resistant. The results showed the fluorine-based compounds in 56 percent of the bread wrappers, 38 percent of the burger wrappers, and 20 percent of the paperboard containers that Peaslee tested. The study drew national headlines.

The fast-food industry responded before the government could draft regulations. “There’s almost no regulation on anything that we eat or drink,” Peaslee says. “But the fear of litigation is a very powerful motivator.” Within 18 months, all 20 companies whose products Peaslee’s lab surveyed had removed PFAS from the paper on their production lines.

It’s long been known that firefighting foams containing PFAS are dangerous to firefighters’ health and can leach into groundwater. Studies by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health found that firefighters have a 9 percent higher risk of getting cancer and a 14 percent higher risk of dying from the disease than the general U.S. population.

Local fire departments commonly work and train with such foams, although some states, including Indiana, now prohibit their use for training purposes and offer collection and disposal programs. The U.S. military is scheduled to stop purchasing PFAS-containing firefighting foam this year and to phase it out entirely by 2024.

After talking to Diane Cotter, the wife of a Massachusetts firefighter who had been diagnosed with cancer, Peaslee and his team tested samples of the protective clothing firefighters wear on the job. Their study, published in 2020, found significant quantities of forever chemicals in the firefighters’ water-resistant gear.

Paul Cotter went through cancer treatment and survived but is now disabled. Burned: Protecting the Protectors, a documentary film about Diane Cotter’s quest to understand decades of heightened cancer incidence in the firefighting community, was released this past January.

Most people ingest PFAS through food and drinking water, says Peaslee. “It’s not an acute toxin. It’s chronic, so it affects you by long-term exposure.”

In March, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency proposed the first federal limits on PFAS in drinking water, setting standards for six such chemicals. Municipal water departments would be required to monitor for the chemicals, notify the public about PFAS levels and work to reduce them if levels rise above permissible limits. The goal is to reduce potential PFAS exposure among the more than 200 million Americans who use municipal tap water.

For now, the safest way to dispose of PFAS-containing material is to bury it in sites designed to contain hazardous waste. The next generation’s task will be to determine how to safely eliminate PFAS, whether through incineration or other means, Peaslee says.

The professor of physics and chemistry reads product labels carefully. He got rid of his own nonstick cookware and switched to ceramic-coated pots and pans. His family no longer buys or wears clothing labeled as stain- or water-resistant or antimicrobial. He avoids buying furniture with fabric that has been treated for such properties and doesn’t buy any products marketed as flame retardant.

Sometimes manufacturers contact Peaslee and tell him they use the “safe kind” of PFAS. “There are no safe kinds. I’ve yet to see one that doesn’t cause some sort of cancer or immunosuppression,” he says.

Testing for PFAS and eliminating their use is expensive, but much less costly — in dollars and in human terms — than medical treatments for those who become ill because of the chemicals, Peaslee adds.

Americans should educate themselves about the products that harbor the chemicals, Peaslee says. “Maybe you’ve gotten away with it, but most of us have it in our blood.”

Some states already are regulating PFAS in certain products. Peaslee predicts the federal government eventually will play an even larger role than the proposed EPA regulations.

Despite the slew of products in which he has found forever chemicals, he’s positive about the progress being made, especially in the last two years. “Before that, I almost gave up a couple of times, because it was just so daunting,” he says.

There’s no point debating whether PFAS are worth the risk, Peaslee says. “If it’s not essential, we should be finding alternatives. And in most industries, there’s a readily available alternative that’s cheaper.”

Companies, like people, generally do the right thing when they learn about the consequences, Peaslee says. “I’ve found the companies respond very ethically when they’re given the choice.”

Margaret Fosmoe is an associate editor of this magazine.