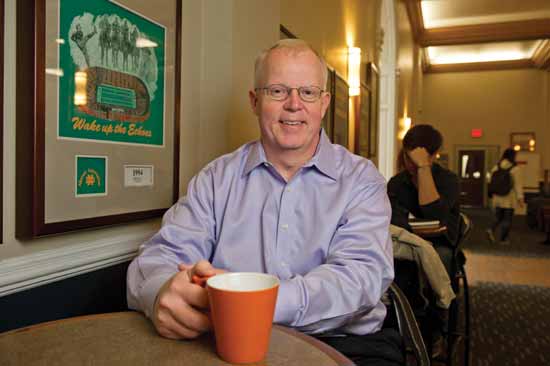

People judge others all the time, and the Notre Dame professor with the appropriate name of Tim Judge probably thinks “What a klutz” when I inadvertently bump our small table. Coffee splashes across the table’s surface and seeps into his printed biographical sketch just as our “having coffee with” chat in the first-floor student lounge of LaFortune begins.

Judge jumps up to get some napkins to stem the tide and then makes an attempt to put red-faced me at ease, commenting with an understanding smile, “At least it didn’t spill on us.”

My initial judgment of him: The management professor with the corona of close-cropped white hair is a nice guy.

My second thought: Is being nice a good thing?

I place the blame for that odd thought squarely at Judge’s door. For in his scholarly career, the current Franklin D. Schurz Professor of Management at Notre Dame’s Mendoza College of Business likes to investigate how personality, physical appearance and even genetics can affect career success. His sometimes surprising results can lead us to rethink any number of ideas we might have about how things work at work.

In the case of niceness, Judge’s 2011 study “Do nice guys — and gals — really finish last?” has me considering the benefits of what’s usually seen as a positive trait. For it appears that, at least when it comes to jobs, “there is a penalty for being agreeable in the workplace.”

As Judge and the study’s co-authors reported: “Nice guys do not necessarily finish last, but they do finish a distant second in terms of earnings,” often because “disagreeable men are more successful in negotiating pay.” For mean girls, the study’s authors point out, the earnings difference is not anywhere near as striking.

The prolific scholar, whose previous professorial stints include the universities of Cornell, Florida and Iowa, has other fun things to share, because personality factors aren’t the only focus of Judge’s research. He’s also done studies on physical appearance and success.

“Really what set me on that course is we did a study on height, and we found that tall people earn more — and it’s significant,” he tells me. “It’s more true for men than women but true for both.”

That unforeseen conclusion opened another rabbit hole for the curious professor. “Because that was such a startling result,” he says, “I started to look at other physical characteristics.”

One result of a study he did is not all that surprising: “We find that beautiful people earn more.” And let’s not even talk about his research on the “weight penalty,” particularly as it applies to women, whose raises can lower when their weight climbs.

While physical attributes do have a bearing on wages, which seems unfair but relatively harmless, Judge points out that looks also affect the political scene, right down to our presidential votes.

“It’s been more than 100 years since we’ve elected a U.S. president who was shorter than the average male,” he says. Tall people are seen as more leaderlike, which harkens back to the study on how height affects earnings.

He ticks off other physical “debits” for the political male:

Facial hair? “Not since Teddy Roosevelt.”

Glasses? “Rare.”

Bald? “When’s the last bald president we’ve had?”

Ugly? “We all know that if you were ugly, deemed that way by others, you wouldn’t have a chance.”

OK, perhaps not so harmless after all. “We like to think we’re a deep society, but sometimes these superficial characteristics have a big impact,” Judge says, warming to a topic that seems dear to him. “We’re dominated a lot of times by these instant impressions, and I’m the same way, we’re all that way. . . . What we have to realize is that often they’re wrong — they don’t mean anything.”

What definitely does mean something, however, is another personality factor.

Around us, as some students in the lounge keep their eyes trained on laptops, others chat as they work. Those behaviors in social interactions, I’m about to learn, could offer a clue about who the workplace leaders of the future may be.

“Extraversion,” Judge says unequivocally, “is the best predictor of leadership emergence.”

The professor quickly reels off a list of three qualities shared by the outgoing among us:

“Extroverts tend to be effusive . . . they show obvious enthusiasm.”

“The sociability factor . . . being a people person.”

“Extroverts like to take charge.”

Of those three traits — expressivity, sociability and social dominance — those who rate high in social dominance are more likely to emerge as leaders. That’s probably because, he says, they are more ambitious than other extroverts.

Introverts, on the other hand, value their quiet time and want to go their own way. That core characteristic of an introvert, Judge says, is one that definitely applies to him. It also may be part of the reason he is so productive as a scholar — research requires some solitude.

Introversion, he admits, doesn’t help in social occasions. He and his wife, Jill, a practicing social worker, are both introverts, and, he confesses, “Parties, for us, are horrors. . . . We end up finding ourselves in the corner with no one to talk to.”

Jill and Tim are the parents of two daughters and a son — Abigail, 24; Martha, 19, a student at Notre Dame; and Carsten, 10. With the mounds of information he’s gathered about factors affecting workplace success, I can’t help but ask, “Given all this, what are you going to say? Stay thin, look pretty, grow taller? What are you going to tell those daughters?”

The question gets a laugh, and then Judge turns serious. “Those things are hard to control, so focus on the things you can,” he says. His advice: “Plans made today, I think, when people are young, have tremendous rewards later. . . . Goals are imperfect things but in general wonderful things.”

That “have-a-plan” advice doesn’t just apply to the young, the 50-year-old stresses. Different stages of life may require new goals; something of particular importance, he says, to retirees.

Whether for his daughters or his students, Judge is also a big believer in internships, which can offer young people an idea of whether or not they really want to be part of a particular field. “Notre Dame is great at this,” he adds. “The engagement part — they really do encourage it.”

Even though the internship advice and his undergraduate class on Management Competencies and his graduate class on Leadership and Decision-making seem to concentrate on career success, Judge is not entirely focused on helping students do better in their jobs. This nice guy also worries about their overall well-being.

Success has two main elements, he says, intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic refers to how happy you are — with your job, your career, even your life. The extrinsic element involves pay, “just the cold hard economics of it.”

“The balancing of the two is often not easy,” he says.

This is where things get tricky, because, he says, “leading an extrinsically successful life is not the same as leading a happy life.” While he doesn’t use the “money doesn’t buy happiness” cliché, Judge does say, “We should realize that wealth, high levels of career success, in and of themselves, are not going to lead to a happy life.”

During classes, Judge says, he emphasizes that it is okay to strive for extrinsic success if that is what the students might want. But he also warns that they should look at their values and at the price they might pay for extrinsic success. “Be careful about the means by which you go about something,” he tells them. He also suggests that students ask: “Are the benefits worth the things we might have to do to make that happen?”

That question of trade-offs in life is often of particular importance to women. Judge says it’s relatively common for female professors to delay having a family because they are pursuing tenure, but they also must consider fertility issues. Getting pregnant later in life might not be possible or it could put a baby at risk for congenital illnesses.

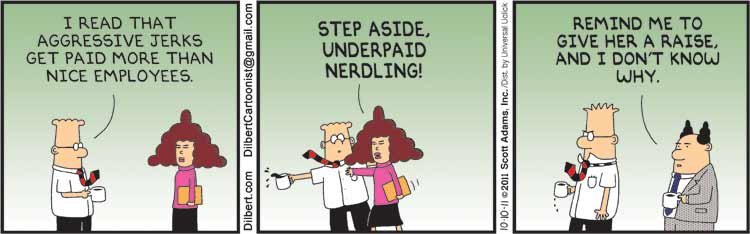

Our talk of the issues women face circles us back to the “Do nice guys — and gals — really finish last?” study, a research topic that even drew the attention of Scott Adams, who used it in his Dilbert comic strip.

Judge’s interest in the subject arose from watching the differing treatment of two powerful people — Martha Stewart and Donald Trump. “Both highly disagreeable people, both just really tough SOBs,” he says, cutting neither one of them any slack.

But it was Stewart in particular, he says, who wasn’t given a break when in 2003 she faced charges of insider trading, eventually being found guilty of obstructing justice and making false statements. Special prosecutor Patrick Fitzgerald “admitted it was selective prosecution of Martha Stewart,” says Judge, who was amazed by the vitriol faced by the domestic goddess.

Yet another powerful woman, Hillary Clinton, faced similar venom when, in 2009, she was named U.S. Secretary of State. “Everything she said was studied in a different light . . . people used lots of negative labels.”

Through his many scholarly studies, Judge has witnessed this disturbing trend: A societal bias against women continues to this day. And that gender double-standard applies both to earnings and to career trajectory. “A woman in charge is much less desirable than people will admit,” he says.

While the “nice guys” study showed that disagreeable men do substantially better in the earnings category than nice guys, the results weren’t anywhere near as pronounced for disagreeable women, who may only slightly outdo agreeable women in terms of salary. The study’s bottom line, however: Men, whether agreeable or not, still earn more than women.

Where does all this leave women, particularly those who are focused on monetary rewards? “They have to be careful not to do social discounting, saying things like ‘Oh, I couldn’t take credit for that,’” he says. “What I tell women is ‘You have to be assertive, not be afraid to be self-interested.’” And, while it may be unfair, women still must temper their behavior, particularly when discussing pay issues. “Be calm, rational, use data,” he advises his female students.

At this point, Judge advises me that another meeting calls for him. Still, in case I had any doubts, the introvert with an extrovert’s enthusiasm for teaching and behavioral research wants to make it clear to me how much his work means to him. “I’ll never get tired of studying individual differences,” he says.

Carol Schaal is managing editor of this magazine.