Mom wouldn’t talk to me for a week.

What was my egregious mistake? Did I say something disrespectful? Did I renege on a promise? Did I commit the unpardonable sin of forgetting our weekly Sunday afternoon phone call?

Nope. Not a chance. Negative, Ghost Rider.

It was worse.

My unfathomable act: I got a tattoo.

And I was 43 years old.

Tattoos had always fascinated me. During my 1980s childhood, they were mainly restricted to sailors on shore leave and people in street gangs. I did not know very many people who had one. Of those few, most were men.

But whether a person was touting where they served overseas in the military, or perhaps professing an undying love to their significant other (very risky), the sheer act of getting a tattoo was both enticing and dangerous. Putting ink on one’s skin, no matter the size and no matter the reason, was so bold. It was so permanent.

Then, as I grew into my adolescent years, an older sibling started getting tattoos. Gasp! These new artistic additions were not to commemorate naval service or to express gang loyalty. They were simply expressions of creativity and personality. A Zodiac symbol on a forearm here. A sports team insignia on a shoulder there. To me they were cool, another symbol of burgeoning older-sibling independence.

In our conventional Latino-Irish household, Mama would have none of it. Tattoos were not only frowned upon, her Colombian upbringing taught her that they were a defacing of the skin. It was like graffiti by a needle. Dad did not really care for them, even though as a Marine Corps veteran, he’d known plenty of tattooed comrades since age 17. But there was one key reason his Irish temper did not boil over like my mom’s South American one. The first tattoo in our family was brandished by a boy.

This revealed some societal stereotypes that were present in our household and beyond. Could my sister get a tattoo? Absolutely not. That was very unladylike. Could I, perhaps when I reached teenage status, put a Padres insignia on my skin? Although I am male, the answer was the same: No! The reason was because I had a physical disability. And people with disabilities, in societal terms, just did not do expressive and aggressive things like that. We were to accept our lot in life and certainly not show off our bodies.

As the years passed, our parents forgave the growing trend of tats in our familia. They still fumed, but they forgave. Piercings also became more en vogue and when my sister — older than me by three years — got her first tattoo and piercings that were not in her ears, I thought Mom was going to faint in her Volvo.

But my parents grew to accept her ink (and piercings) too. Because society was starting to accept that, yes, women liked to express their thoughts and feelings through skin art as well.

In the new millennium, I started noticing fellow disabled people not only stop hiding, but start celebrating their disabilities on their bodies. Guys in wheelchairs brandished ink of their mode of transportation with trailing flames. Women who were amputees, or had some other form of disability, espoused their sexuality with art of provocative body types.

But never me. I did not believe my family, including aunts and uncles, would approve. I did not believe society would approve.

Until the summer of 2017. Two months after my 43rd birthday, my biological father passed away. (The parents who raised me were actually an aunt and uncle.) Having grown up, for numerous reasons, not getting to see my father much left an impenetrable hole in my heart. Although I was not raised by him, I still loved him. I had so many questions about him. Everyone who knew him consistently brought up ways I was like him, both in resemblance and behavior. I badly missed a man I barely knew.

So I broke all previously held societal norms. I marched right into a tattoo parlor in my East Village neighborhood in San Diego and asked to speak to an artist. I explained about my father, who had died only two days earlier, and that I wanted three things emblazoned on my right shoulder — his name, the name of another sister who had died of cancer five years earlier, and a cross. The cross was crucial because of my Christian faith and, unlike a sports team or political party, I knew I would never renounce it.

He obliged with their names written as a scroll draped over a cross. It was the most liberating $200 I had ever spent.

It was a permanent memorial, one I could glance at and feel comforted in moments of melancholy. A midlife crisis? Perhaps. But I was grateful for this indelible inscription.

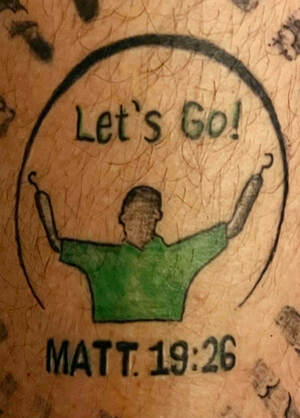

As time has moved on, more tattoos have been added to my body. A heart surrounded by Colombian and American flags. A picture of me with prosthetic arms raised aloft, urging others, “Let’s Go!” My favorite line of Scripture, from Matthew 19:26: With God all things are possible.

An homage to one of my mentors at Local Church, who went to heaven this year.

An homage to that same Mom, when she went to heaven in 2019.

Before she died, she called me on a Sunday, right after I added the U.S.-Colombian tattoo.

“How’s your left shoulder?” she asked. “Did the ink dry?”

Alex Montoya is a diversity and equality author and speaker who resides in East Village San Diego. He can be reached at alex@alexmontoya.org.