As Bob Livingstone waded alone toward the beach of the Philippine island of Luzon, he heard a quiet splash in the murky water behind him. He swiveled, his cumbersome Army pack slowing his motion as he struggled to find the source of the sound.

He heard another splash. Sweat smothered his face in the tropical jungle heat. His eyes darted over the water.

Then he saw them: sea snakes. Swimming toward him.

Luzon has one of the highest concentrations of sea snakes in the world. Most are as passive as they are venomous.

Livingstone churned the water, desperately maneuvering away from the snakes as they swam toward him. He had always been fast, but in the shallows of Luzon the soldier was no longer the predator.

- Related articles

- A Land of Myth and Legend

- In a League of Its Own

Finally, as he staggered up the beach, he thought to himself: What the hell am I getting into here?

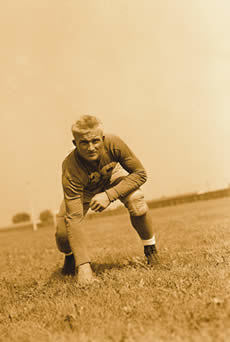

In 1941 and 1942, Livingstone distinguished himself on the football field for Notre Dame. But with the military draft looming, the speedy halfback enlisted so he could finish his sophomore year. By the summer of 1943, while his fellow players were preparing for a run at the national championship, he traveled from his home in Merrillville, Indiana, to Army boot camp in central Texas. When the Army sent him to Fort Ord in Monterey Bay, California, Livingstone knew he was bound for the South Pacific: He sailed to the Philippines.

By January 1945, the Army readied for its final push through the Philippines. General Douglas MacArthur had already retaken Leyte and Mindoro. Luzon awaited.

As dawn broke on January 9, nearly 70 Allied warships sailed into Luzon’s Lingayan Gulf. Soldiers from the 6th Army and two corps of Marines watched from their landing boats as American battleships and heavy cruisers sent artillery volleys on high. Thunder shook down from the sky.

Livingstone arrived on Luzon after the main invasion force, when the primary shoreline combatants were sea snakes. He and other reinforcements had to clear out remaining Japanese soldiers, who still launched daring nighttime raids against American camps.

Once he was on the beach, a guide took him to his tent. Exhausted, Livingstone set his rifle against the tent wall and peeled off his sodden gear. As Livingstone was lying down on his cot, the guide popped his head back in the tent.

“Where’s your rifle?” the guide asked.

“It’s over there,” a tired Livingstone replied, gesturing to the side of his tent.

“You’ll want to keep that loaded and at your side,” the guide said. “The Japanese like to sneak into the tents and kill the soldiers in their sleep.”

Livingstone grabbed his rifle and slipped a bullet in the chamber.

He didn’t get much sleep that night.

Over his two-and-a-half years in the South Pacific, Livingstone survived hand-to-hand combat with Japanese soldiers. He fought in New Guinea, where Japanese soldiers frightened the Allies as much as the local headhunters.

He returned home in time for Notre Dame’s 1946 football season. When he got home, his father made a phone call.

It was to Frank Leahy.

_ _ _

In the summer of 1946, Indiana’s warm zephyr winds carried more than the peals of bells from Sacred Heart Church across the verdant quadrangles of Notre Dame. They brought joy.

The war was over. The GIs were coming home.

Across the nation, war-weary Americans rejoiced as their spirited young men returned, some from the battlefields to the playing fields. With the GI Bill returning GI Joe to campus, the nation’s football fans and coaches readied for the greatest influx of talent the college game had ever seen.

“With three thousand rahs and a tiger the old-time banners climbed the pole again, and no autumn’s winds have whipped them braver or brighter,” sang Wilton Hazzard in the 1946 All-American Gridiron Preview.But some fans of the game feared that veterans, shell-shocked from the brutality of the war, could not — would not — readjust to college life. Some grizzled men, they dreaded, would bring their “gouging, rock ’em-sock ’em carnage” from the battlefield, wrote John DaGrosa in The Official NCAA Football Guide, 1947. Other coaches feared the ex-GIs’ “unwillingness to accept — after military regimentation — necessary football discipline.”

But for 53 ex-servicemen who stayed in South Bend in that halcyon summer, there were no such concerns. They came to an all-male campus, strictly minded by the watchful eyes of the Holy Cross brothers and priests, who enforced lights-out at 10 and thrice-weekly morning Mass at 6:30. Some priests, seeing the ex-soldiers’ unseen battle scars, loosened their grips. A little.

Most important, the 53 ex-servicemen were now serving a tour of duty under a former Navy lieutenant who commanded with a steely gaze, a soft voice and an obsession with winning: Frank Leahy.

Leahy arrived at Notre Dame from Boston College in 1941. By 1943, the taciturn Irish-Catholic steered the Irish to a nine-win record and Notre Dame’s first national championship since Knute Rockne. Soon after, he had been “drafted” right off the football field: The government made him a first lieutenant in the Navy as a celebrity-soldier and placed him in charge of recreational activities for submarine crews in the Pacific.

Even during the war, Leahy scouted and recruited the most talented stars in the service. He pursued monster tackle George Connor in Pearl Harbor. Livingstone, fresh off a boat from the Pacific, had returned at halfback. Halfback Emil “Red” Sitko and center George Strohmeyer came from stellar careers on football teams at military bases.

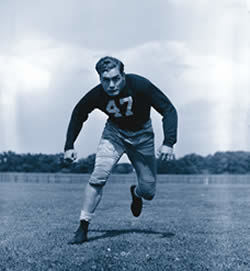

And at left end was a new face: a 22-year old ex-Marine Leahy recruited in the jungles of Iwo Jima. In an era before players lifted weights, the 6-foot 2-inch Bronze Star winner packed 204 pounds of lean muscle and a granite jaw. His calves measured 17 inches. One of his brawny arms bore an imposing tattoo of a sword cutting through a dragon. “Death Before Dishonor,” it said.

His name was Jim Martin. They called him Jungle Jim.

_ _ _

The moon had not yet risen on the night of July 10, 1944, when Jim Martin and his fellow Marines set their paddles in their rubber boats and slipped into the inky black South Pacific.

Smoothly, quietly, they swam toward the shoreline of Tinian, a Japanese-held island in the Marianas. Clad only in black swim trunks, flippers and dive masks, Martin and his fellow soldiers started the 500-yard swim to the sand designated Yellow Beach. They did not know what they would find.

As Martin swam closer to the beach, he could see below him outlines of urchin-like spiked balls chained to the ocean bottom.

Sea mines. Many of them. Floating less than an arm’s length below.

He kept swimming.

In the summer of 1944, American military forces were in the thick of jungle fighting as they island-hopped their way across the Pacific. By July 3, Marine Lieutenant General Holland Smith, the commander of the Expeditionary Troops, had nearly secured the island of Saipan, a crucial foothold in the Mariana island chain that offered airfields for super-long-range bomber strikes against Japan. With victory in Saipan assured, the Fifth Amphibious Corps turned their sights to Tinian, a plateau island less than five miles from Saipan’s southwest coast. Flatter than Saipan and already home to several bomber-ready airfields, Tinian was the obvious next hop toward Japan.

But before American forces could attack the entrenched 9,000-strong Japanese garrison, commanders needed to find cliff-ringed Tinian’s weak spot. In the early island battles of the Pacific campaign, U.S. generals had watched helplessly as their landing forces foundered on coral reefs and Japanese minefields. Some Marines, forced to abandon landing crafts while wearing 60-pound packs, drowned before they could set their boots on sand.

So on July 9, when the Army and the Marines officially wrested Saipan from the Japanese, Lieutenant General Smith alerted Captain James L. Jones that Jones’ Amphibious Reconnaissance Battalion would be scouting Tinian’s beaches to find weak points where American troops could land and be supplied.

Jones assembled a veteran force of expert swimmers: Marine Companies A and B and two of the Navy’s elite Underwater Demolition Teams (UDTs). These men, predecessors of the modern Navy SEALS, were the first wartime experts in amphibious reconnaissance and demolition. By the end of the war, they had perfected the delicate art of swimming underneath enemy ships, planting explosives and swimming away quickly enough to watch the explosion from a safe distance.

Martin had been a championship football player and swimmer during his high school days in Cleveland, but swimming over sea mines and under warships in the South Pacific was a far cry from the local pool.

On July 10, Martin boarded the destroyer transport USS Gilmer with 19 fellow Company A Marines and eight UDT swimmers. Under cover of night, they sailed from Saipan’s Magicienne Bay toward Yellow Beach. At 20:30, Martin climbed into a rubber boat with Olie Kelson and 2nd Lieutenant Donald Neff and paddled toward Tinian’s southwest coast.

Martin, Kelson and Neff reached the shoreline. The beach, flanked by imposing cliffs, was thick with double-apron barbed wire fences. Martin saw spotlights dance across the beach approaches. Then: gunshots. The men tensed.

Leaving Martin and Kelson at the high-water mark, Neff stalked 30 yards inland. He saw three Japanese sentries on a cliff overlooking the beach. Gunshots again — but not from the sentries. Neff heard Japanese work crews talking as they built pillboxes and trenches. The “gunshots” were blasting charges.

The Navy divers and Marines had seen enough of Yellow Beach. Treading softly through the sand, they slipped once more into the Pacific’s briny blackness and swam back to their rafts as silently as they had left.

- – -

The veterans of Notre Dame’s 1946 team were steely men, born in the Depression’s hungry mold and hardened by some of the war’s most hellish blast furnaces. They had survived those battles.

But before they could truly trade in their olive drab for Kelly green, deep blue and burnished gold, they had to survive Frank Leahy’s practices.

The great coach imposed his sheer determination to win as he recast the soldiers into a glinting mechanical beast like South Bend’s magnificent chrome Studebakers. Everyone knew Notre Dame would be good, but even the fiercest fans acknowledged that the Irish schedule brought Leahy’s troops against the nation’s finest squads: Illinois. Army. Southern California.

With almost 200 men trying out and all 11 starters playing both offense and defense, Leahy and his assistants ground their men through hellish practices in pursuit of the fiercest 11 the Fighting Irish could field. The assistant coaches, often former Irish players themselves, frequently joined the fray.

Leahy’s practices were brutal, born of his experience as a tackle during his playing days under Rockne and his boyhood in Winner, South Dakota, where his father, a freight handler, taught boxing and wrestling to young Francis and his three brothers.

One such drill, the “Murderer’s Row,” pitted backs against vicious hits from all 14 tackles, then all 14 guards and finally the centers. In the “Box drill,” players stood in a marked square on the field while another player ran full speed into him: if the runner crossed the opposite line of the square, the tackler had failed. Leon Hart, then a 17-year-old freshman, once bulled into a tackler so hard he knocked the man unconscious and sent him flying. Leahy couldn’t help himself: “God bless you, Leon!” he blurted.

There was no drinking water. With leather helmets, thin shoulder pads and minimal thigh and knee protection, injuries were frequent and disregarded: The best men could play through injuries, or at least ignore them, in the face of such competition. John “Pep” Panelli, a fullback on the team, broke his nose seven times in practice over his career. He learned how to re-set it without coming off the field. The uninjured players who survived Thursday scrimmages would make it to the traveling team.

“Practice was tough on the older service vets,” Martin said later. “They’d had enough of war, of guys beating the hell out of each other, but that’s what practice was every day — a war.”

Surrounded by the sound and fury was Leahy, a hardened and obsessive source of order. Never one to shout at players, Leahy instead ruled with a polite lilt and a ferocious stare. He avoided profanity, even though the results often sounded silly: Jack Landry, a fullback on Leahy’s 1949 team, remembers Leahy urging his players to “hit them so hard you make them feel ill!”

Leahy always used a player’s full first and last names, even when he found tackle and clown prince Ziggy Czarobski showering before practice: “Zygmont Czarobski, what in the world are you doing?”

“Coach,” Ziggy quipped, “it just gets too crowded afterward.”

Leahy’s 1946 squad was widely regarded as a formidable football force in season previews. (“The tackles,” noted Francis J. Powers, “are five-deep in thunderosity.”) But Leahy was famously pessimistic toward his team’s prospects, and perhaps rightfully so. The first game of the 1946 season pitted the favored Irish on the road against the vaunted “Leatherneck line” of Illinois, which featured seven ex-Marines. Illinois also had one of the first black collegiate football stars in Chicago’s Claude “Buddy” Young, a running back that Hazzard called “the nearest approach to a cleatshod bolt of lighting the game has known.” Illinois had demolished Pittsburgh 40-0 the week before. Writers called for an upset of the Irish. Leahy fretted.

But Leahy’s lads crushed Illinois to the tune of 26-6, bottling up the lightning bolt and flashing through the Leatherneck line. Then they steamrolled Pittsburgh 33-0, as Johnny Lujack and George Ratterman passed for 257 yards.

Leahy was furious. He complained about player after player to Jim Costin, the South Bend Tribune beat reporter. (He may have been pessimistic, but this was also a classic Leahy tactic: rip the players when they’re riding high, but leave ’em when they’re down.)

“Didn’t anyone play well?” a surprised Costin asked Leahy.

“Yes,” the dour coach replied, thinking of a third-string guard. “Bob McBride.”

- – -

On frozen feet Bob McBride marched.

Through the snows of the nightmare Ardennes Forest the Army soldiers trudged, prodded by German rifles on the long march to a prisoner of war camp.

McBride and his fellow soldiers of the 106th Division had not expected such a sudden and ferocious attack from German forces. Allied forces scrambled for defense against a thunderous German offensive as snows dusted the bleak Belgian forests.

The Germans called it Operation “Watch on the Rhine.” When the Americans realized what hit them, they called it The Battle of the Bulge.

McBride had only arrived on the western front in October 1944. After three standout seasons at right guard, including two seasons under Frank Leahy, he joined the Amy in the spring of 1943.

McBride’s 106th Infantry Division, nicknamed the “Golden Lions” for their blue-and-gold lion’s head insignia, had relieved the 2nd Infantry Division on the Belgian Front on December 11, 1944. Only five days later, German regiments bombarded the 106th with a last-ditch offensive. With overcast skies grounding the dominant Allied air forces, McBride’s unit was woefully unprepared. In two days, the Iron Cross encircled the 422nd and 423rd Infantry Regiments near Schonberg, forcing them to surrender on December 19.

McBride and the rest of the 106th withdrew over the Our River to the strategically important rail and road junction at Saint Vith. For five days, the vastly outgunned and outmanned Americans stubbornly clung to Saint Vith against thousands of veteran German troops. McBride, a machine gun commander, held a thin ridgeline with the rest of the 106th for five days. On December 21, the 106th finally retreated under a curtain of enemy fire. They didn’t know it then, but their defense had ruined the German timetable, dooming the Axis counteroffensive.

During the retreat, German soldiers captured Bob McBride. Like thousands of men from the 106th, he became a prisoner of war.

For 13 days, German soldiers guarded McBride and his fellow soldiers as they slogged through snow and mud to German prisoner camps. Once the German offensive “bulge” collapsed, the prisoners again marched, this time for 50 days, alongside the German retreat.

Most of the German soldiers are civil people, McBride thought. They’re like neighbors of ours back in the United States. But a few are mean and rotten to the core. If you just fall down while you’re out walking, there are Hitlerites who will come up, put a rifle to your head and blow your brains out.

With a starvation diet of only one-seventh of a loaf of bread per day, the burly McBride, whose Notre Dame jersey had snugly fit around his muscular 210 pounds, started to shrivel. He languished in captivity for 123 days.

On April 23, 1945, he heard voices shouting in English: American troops had arrived. The first doctor to find McBride introduced himself as Dr. Schneider. He had studied pre-med at Notre Dame.

“Are you related in any way to the Bob McBride who played football at Notre Dame?” the doctor asked.

“Yes, I am,” McBride said.

“What relation?”

“I’m him,” he croaked. “I’m Bob McBride.”

Dr. Schneider surveyed the spindly figure before him. He can’t weigh more than 100 pounds, he thought. Closer to 90.

The doctor delivered his prognosis with one word.

“Bullsh——.”

- – -

They called it the Game of the Century.

Many of Notre Dame’s men had vanquished the Axis powers and some of the nation’s best football squads. But in the season of 1946, Leahy and his lads had one final battle to fight before they could prove their football dominance. They had to defeat the No. 1 team in America: the Army Black Knights.

After Illinois and Pitt, Notre Dame scored victories over Purdue, 17th-ranked Iowa and Navy. But Army’s team had pulverized the war-depleted Irish in 1944 and 1945, running up the score over the Leahy-less squads for a combined score of 107-0.

The Irish wanted victory. They wanted revenge. On November 9, 1946, they got their chance on the biggest stage in college football: Yankee Stadium.

Never before had a game so captivated America. The stories played out in the papers and on the radio. Army had its Heisman-Trophy-winning “twin atomizers”: Felix “Doc” Blanchard and Glenn Davis. Mr. Inside and Mr. Outside. The Touchdown Twins, rulers of the gridiron with impunity. Army was riding a 25-game win streak and seriously contending for its third national championship in a row.

Tickets sold at astronomical prices. On the morning of the game, one man sold a $3.30 ticket for $200, worth roughly $2,200 today. Jim Martin’s girlfriend in Cleveland asked for two tickets. He made her pay $50 each. He never saw her again. (“Can’t be lucky all the time,” he later mused.)

Both Leahy and Army coach Colonel Earl “Red” Blaik had prepared for the game with utmost secrecy. Leahy had sent managers into the trees overlooking the practice field. When planes flew overhead, he only called conservative run plays. “Oh, there go those Army scouts,” he would say.

Back and forth the green and black lines warred, each rumbling tackle eliciting cheers from the wool-clad thousands under the blue-gray November sky. Martin roared all over the field, stonewalling the Touchdown Twins again and again. The ex-soldiers again fought a trench battle — but this time they launched their aerial attacks and driving assaults on a gridiron. Some said the generals tightened up, perhaps out of pride or out of spite: Neither Leahy nor Blaik even considered kicking a field goal. The game ended in a spectacular 0-0 tie.

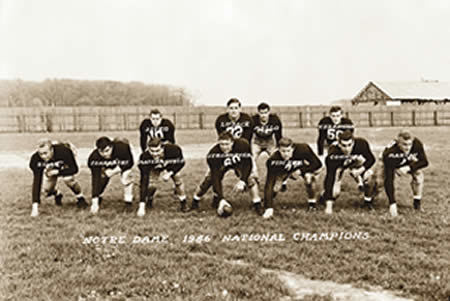

It didn’t matter that Notre Dame tied Army. As far as the press and the fans were concerned, the Fighting Irish had vanquished the Black Knights. Notre Dame went on to win each successive game and was awarded the National Championship. Grantland Rice, legendary sportswriter of “The Four Horsemen” fame, picked Lujack, Connor and guard John Mastrangelo for his All-America team.

One storyline avoided notice. At the end of the season, Notre Dame’s Department of Sports Publicity released its official Recapitulation of the 1946 Notre Dame Football season. After he had returned home from a prisoner of war camp, doctors told him he’d probably never play again — or have children. Over the summer of 1946, he worked construction and ate nonstop. At 180 pounds, he was still too light to start. He had already been awarded three battle stars, a purple heart and the presidential unit citation. But when the monogram list was published with its neat rows of typewritten ink, Assistant Director Charlie Callahan made sure to include a third-string guard from Lancaster, Ohio.

Bob McBride.

- – -

Although he was relegated to a backup role, McBride was an inspiration for his teammates, who admired his unyielding determination to succeed, what though the odds be great or small. He had a brief career coaching high school football before returning to Notre Dame as one of Leahy’s most trusted assistant coaches. Although his players remembered him for his demanding coaching, they held him in high esteem, and he coached several All-Americans on Notre Dame’s line, including Jim Martin.

“Jungle Jim” Martin was awarded a Bronze Star for courageously swimming through fields of sea mines in advance of American forces in the Pacific. He never lost a game at Notre Dame and won three national championships with the Irish. His teammates regarded him as a leader, and he often reciprocated their admiration by taking them to dances at South Bend’s American Legion Hall. (His teammates danced with their dates, and he danced with their dates’ mothers.) He won All-American honors at both end and tackle positions before his 14-season professional career as a linebacker and a placekicker, including a 1961 Pro Bowl selection.

Bob Livingstone was drafted by the Chicago Bears after the 1946 season but returned to Notre Dame in 1947 to finish his degree. During the championship 1947 season, he scored a touchdown on a 92-yard run against Southern California, a Notre Dame record that still stands.

Leahy’s teams won national championships in 1943, 1946, 1947 and 1949, with the 1948 powerhouse unbeaten until it finished its season with a surprising tie against USC, leaving Michigan with the national title. But no team so encapsulated the fighting spirit of Notre Dame’s teams like the 1946 Fighting Irish: a ferociously competitive squad, united by its will to win, forged into greatness by a demanding coach for the glory of Notre Dame.

Michael Rodio was this magazine’s spring 2012 intern. He graduated in May with a degree in music and a minor in the Gallivan program for Journalism, Ethics and Democracy.

Andy Panelli is a marketing executive from Homer Glen, Illinois, and the son of John “Pep” Panelli ’49, a starting fullback on the 1946-48 Irish football teams. In 2007, the younger Panelli took the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the 1947 championship to interview players, coaches and sportswriters from that era “to investigate whether the ’46 and ’47 teams may have been the best college football teams ever fielded.” He is at work on a documentary on that subject, expected to be released later this year.

Photos from University of Notre Dame Archives.