A friend once asked me, “How do you know when someone went to Notre Dame?” I said I didn’t know. He responded: “They’ll tell you.”

Such is the pride, sometimes obnoxious, of the Notre Dame graduate. I’m one of them. And when people learn I’m a Notre Dame alumnus, most “ohh” and “ahh” about how lucky, how smart, how well off I must have been to go there.

The reality was quite the opposite. My experience of Notre Dame was different — very different — from that of 99.9 percent of my classmates. My Notre Dame wasn’t hanging out in the dorm, football Saturdays, mixers with Saint Mary’s girls or dates with townies, playing pickup basketball at the Rock, or anything close. Saturdays were for work — pumping gas in downtown South Bend, selling clothes at a chain store on Lincoln Way West, checking coats at the dances. Other days of the week were pretty much the same, sans the coat-checking. I took courses at Notre Dame; except for freshman year, I wasn’t part of the life at Notre Dame, to my regret.

I am the oldest of 10 children, born and raised in Holyoke, Massachusetts. The city is on the Connecticut River. It became the center of the country’s paper industry in the 19th century and was a magnet for immigrants — Irish first, French Canadians next, Polish last. My grandparents all came from Ireland. Jobs in the mills were plentiful, and though we stuck close to our ethnic neighborhoods, almost all of us were Catholic. Holyoke was safe, family-oriented, lower middle class. It signaled solidarity. Everyone was a Notre Dame fan. Everyone.

The only thing we, and many other big families, lacked was money. Our family of 12 lived in a house with three bedrooms and a single bathroom — with one tub, no shower. Tuesday and Saturday were bath nights for us kids. It was efficient, but unwieldy. The bathroom was upstairs. A small water heater in the rough basement put out enough hot water for maybe two of the bathers. So, we would heat water in pots on the kitchen stove downstairs and rush upstairs, assembly line style, to deposit the water into the tub. Over and over and over again. Until the last child was clean, or at least wet, cleanliness being dubious after a half-dozen had preceded him or her in the tub.

My father ran a small print shop. An only child, he was a Notre Dame graduate, quite an achievement for a kid from Holyoke when he entered in the 1920s. He chose Notre Dame because his first cousin, James McCarthy, was dean of the College of Commerce, as Notre Dame’s business school was called back then.

Freshman year

I was permitted to apply to only one college. Of course, Notre Dame. My Notre Dame adventure began when my parents saw me off at the Springfield, Massachusetts, train station with a kiss and a wave and instructions to “write when you get work.” My only possession was a clothes trunk heavier than I was. And $10. I had to be the poorest sonofagun ever to enter Notre Dame. The chances of me sticking it out and graduating were a million to one.

My first order of business, after moving myself and the damn trunk into my dorm room as a freshman, was to report to the library to take up a job as a bookbinder. My task was to take ancient, decaying volumes and put them back together. I was equipped with a pot of paste, leather sheets and a pair of scissors. I worked alone in the basement and lived in Zahm Hall with a great group of guys. I felt liberated taking courses with professors who cared about their subject and their students. It was fine. My parents helped pay for my first year.

The summer after freshman year I worked, as I worked each summer, on construction as a laborer, in the paper mills, in a brewery across the river, even as a migrant laborer on a tobacco farm in Connecticut. It was all backbreaking work, but the pay was good.

Sophomore year

It became clear just before I started my sophomore year that I didn’t have enough money to live at the University, paying for a dorm and dining privileges. My parents paid first-semester tuition, but the rest was up to me. So, I found a room about a mile from campus and walked to and from class every day, rain or snow (mostly snow). I continued to work for a time at the library, then got a job at a gas station about 1 1/2 miles from my apartment. I walked an awful lot. I spent more time pumping gas and in my boardinghouse room than I did at Notre Dame.

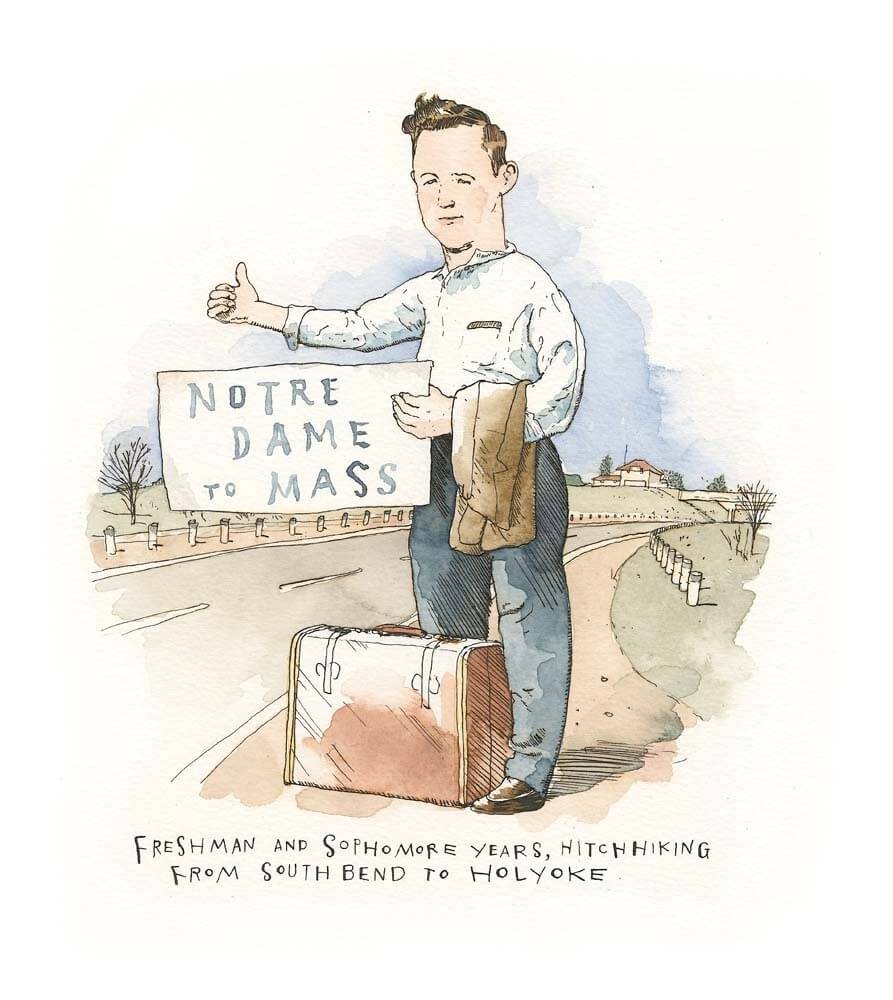

Getting back and forth between Holyoke and South Bend was tough, especially during the holidays. Trains were expensive, and plane travel was not an option. So I improvised. Freshman and sophomore years, I would hitchhike the 800 or so miles from South Bend to Holyoke and back. I would walk to the entrance of the Indiana Toll Road with my suitcase and a sign that said NOTRE DAME TO MASS, hoping to be picked up by a Catholic family that got the double meaning of “Mass.”

I had many an adventure thumbing the Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York and Massachusetts turnpikes. After being stuck for hours on the Ohio Turnpike one freezing night at Christmastime, a Volkswagen Beetle — a novelty in those days — stopped. I opened the passenger door, tossed my suitcase on the back seat, and noted that the driver, a woman, was pointing at me with a bloody hand and uttering, “You’ll save me . . . you’ll save me. . . .” I also noted that another car pulled up 50 yards in front of us, and that the driver, a man of about 35, was striding our way.

Instead of pulling away, the woman rolled down her window, and as the man reached the car, started yelling, “He’ll save me! He’ll save me!” pointing to me, next to her, wondering what the hell was going on. The guy kept looking from the driver to me, obviously sizing me up. I was writing headlines in my mind: “Notre Dame Student Frozen Dead on Ohio Turnpike with Unidentified Older Woman.” Something like that. Anyway, hunched in the small passenger seat of a VW Beetle, at 6 feet, 2 inches, I must have looked like a giant, so he strolled back to his car and out of my life. The woman said she had stopped in a bar to ask directions, got talking to the man in question and unaccountably ended up in a field with the guy, who tried to assault her with a knife. She fought him off but sliced her hand while knocking away his weapon. She took me all the way to the Massachusetts border. She saved me!

To get home junior and senior year, I transported fellow students to and from the Holyoke-Springfield area. I would get $20 from each of my riders and then, and only then, buy a very, very cheap Studebaker, which was manufactured in South Bend. I’d get a 10- to 15-year-old car for maybe $50, then use the rest of the money for gas and oil, which back in the day were extremely cheap. One trip I used 50 quarts of oil, one way. I’d also sneak off the interstate when possible to avoid the tolls, catching a parallel road. That usually worked well, except for one time, I sneaked off the New York State Thruway via a section of farmland littered with rocks. I thought I maneuvered well until a car pulled up beside me to point out my gas tank was leaking badly. I had snagged it on a rock. Remarkably, bubble gum plugged the hole.

Junior year

By the time I was supposed to begin my junior year, my sisters Peggy and Kate were attending a Catholic junior college in Washington, D.C. The best course for the girls and the family in general was for me to drop out of Notre Dame. I’m sure my parents were heartbroken; I was indifferent, not seeing an alternative, but determined to return.

For the next year, living back home in Holyoke, I held a series of jobs saving up for a hopeful return to Notre Dame. I was a laborer — wicked work in the middle of winter on a snowy construction site — a newspaper reporter, a shoe salesman at the local emporium, and I did other menial jobs I can hardly remember.

I returned to Notre Dame the following September, once again living off campus but this time in the basement of a boardinghouse, and I worked two jobs, one selling men’s clothes at Robert Hall, a nationwide chain since defunct, and the other at the gas station. I hardly remember my junior year. I majored in English because my father, an impractical man, demanded I major in literature, history or philosophy.

I couldn’t afford $25 a month, but jail was free. More precisely, I moved out of The House of Bread into a jail cell as an employee of the St. Joseph County juvenile detention center.

Senior year

Senior year was the toughest; I’m not sure how I paid tuition the first semester. I definitely did not have money for food and lodging until I found a decrepit apartment with two other students in the back of an old, beaten-down house in a South Bend neighborhood that Notre Dame deemed unsafe — and grounds for being expelled from the University.

The house was managed by a wonderful, anarchist, Catholic baker whose name I remember as Terry McInnerny. Terry’s tiny bread store, The House of Bread, was in the front of the house. Terry would bake bread all day, often leaving to hit the bar next door to watch fights on television. A peace-loving anarchist who loved boxing! Many days I “watched” the store while he watched the fights. If I wasn’t available, he’d put out loaves of bread on a counter and trust people would put money into the jar he left out. I don’t think he made more than a few dollars a day to support his wife and three kids.

We students lived in the back of the house for $25 a month, total. The place had a dark, greasy-green kitchen, a toilet without a door and a single bedroom with three beds, including a bunk. Split three ways, our rent was $8.33 each. That I could afford. What my roommates and I could not afford, however, was to catch bubonic plague, which we surely would have given the dank, dark, blackish, putrid 50-year-old mattresses on the beds. What to do?

We improvised, again. At the expense of the University, I hate to say. But desperate times call for desperate action. The roommates — one of whom went by “Citizen Ross” — and I donned workingman’s outfits, scurried up to Notre Dame a week before students arrived and, carrying pads and pens to look like we belonged in the dorms, “borrowed” three brand new mattresses. Being good Catholics, we suffered from guilt — but not the plague.

Mattress Week, as we called it, was a good week. However, a few days later, the parents of my roommate Jack from southern Indiana, the roommate with a car, showed up. The mother walked into the dim kitchen, which housed a broken table and a gas stove from the early 1900s, and said, “Son, pack your bags, you aren’t staying here!” Cowed, Jack quickly packed and left for parts unknown. Suddenly the rent was $12.50 monthly, a blow, but manageable.

Eating was still a problem. I used to hang outside the dining hall hoping I could grab something off someone’s tray. One day I spied a container holding a dozen quarts of orange juice sitting on a counter in the deserted room. Desperate for vitamin C, I grabbed the box, ran to a friend’s dorm room and hid my prize under a bed. Later that semester I made an arrangement with one of the guys who checked in students for lunch, paying him a little cash under the table. I had one good meal a day, even if I was a thief, again.

My situation never affected my mood. I was blessed with a cheerful disposition. I accepted my relative poverty; I thought it would be good training for becoming a monk. But then the unthinkable happened: My 14-year-old sister, Mary, was killed in a car accident. October 3, 1959.

Tough times I could endure. Feel good about beating them. My sister’s death, never. Could never accept the pain — mine, of course, but more the pain of my parents. Sitting on the couch, holding each other, weeping, an image that haunts me today, and every day.

Some at the funeral tried to console us: “It’s good there are so many of you.” No, love is indivisible. I didn’t give my sister 10 percent of my love. I gave her 100 percent. To all my siblings, as every member of a family does.

The most painful part of my sister’s death was my mother having to gather up her clothing, a diary, schoolwork, photos — memories of a child she would never see again. When I was leaving to return to Notre Dame, my mother stopped me and said, “Sean, I think God made a mistake.” She had prayed each day to God and his mother, Mary, to take care of her children. And my mother’s daughter Mary was taken from her in the most brutal way.

When I returned to my life in South Bend, took up my work, took up my studies, I was a dead student walking. I was concussed. I wasn’t all there. I was in my Spartan bedroom, but I can’t recall Citizen Ross’ presence. I remember beating my pillow, whimpering, cursing. But I had to do what the living do; I plowed on.

At Christmas, I received a letter from Citizen Ross telling me he was moving out of our apartment “because of your constant influx of friends and relatives.” My brother Dan was playing football at Ball State Teachers College in northeastern Indiana and came to visit often with friends and an occasional cousin. So, Citizen Ross was gone by the time I returned from Christmas vacation.

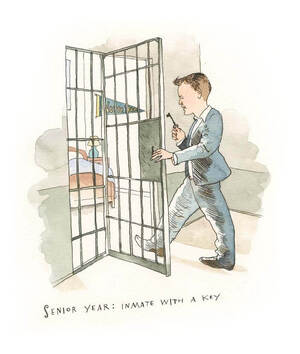

I couldn’t afford $25 a month, but jail was free. More precisely, I moved out of The House of Bread into a jail cell as an employee of the St. Joseph County juvenile detention center. I was a supervisor in the jail, working the 11 p.m. to 7 a.m. shift. If there was trouble, a new inmate intake, an attempted murder, whatever, I was Johnny on the spot.

My compensation was the cell, exactly like the inmates. However, I had a key, and they didn’t. I also received three meals a day and $20 every two weeks. The food was not real food, near as I could tell. The authorities weren’t into gourmet meals for criminals, so I got the gruel they got. It was marginally inedible. Still, as desperate as I had been, and as bad as I felt about what Notre Dame would say about me as an off-and-on, two-bit criminal, I rationalized that since I was “doing time” in the “Big House,” I was, in a sense, absolving my sins.

I made it a point to befriend some of the inmates, as most were good kids, the murderers aside. In one case, authorities assigned me to watch over one of the inmates. He was more a semi-inmate, as he had an outside job, and would spend the night at the jail. The young man was Louis O’Banion, the grandson of Dean O’Banion, the notorious leader of the Irish mafia that ran the illicit liquor business during Prohibition on Chicago’s North Side. Louis never met his grandfather, because Dean was gunned down in 1924 by the Italian mob.

Anyway, Louis was a good guy, uneducated, unsophisticated, impractical. He grew up in backcountry Indiana. Louis took me home to a country cousin’s dance one evening. It was so different from the University, my hometown, even my jail, that I felt I was on a movie set. His people were friendly when they weren’t feuding, and when they weren’t feuding, they were dancing to fiddles.

I commuted the 3 miles between school and jail each day via bicycle. Louis, who had the run of the jail because of my “positive” influence, stole my bike one day. He was in love, and the only way he could get to his beloved one cold day was to buy or steal a bike. True to his heritage, he stole it. The authorities were outraged. Louis was banned from jail because of the theft. I elected not to press charges, and my bike was returned.

Though the jail gave me cell and board, I still had to find tuition money. I thought that between income from the jail and occasional work at the gas station, I would be able to pay over time. So off I went to see the Notre Dame financial authorities, confident that my devout mother’s prayers would be answered: a son who graduated from the Blessed Mother’s University.

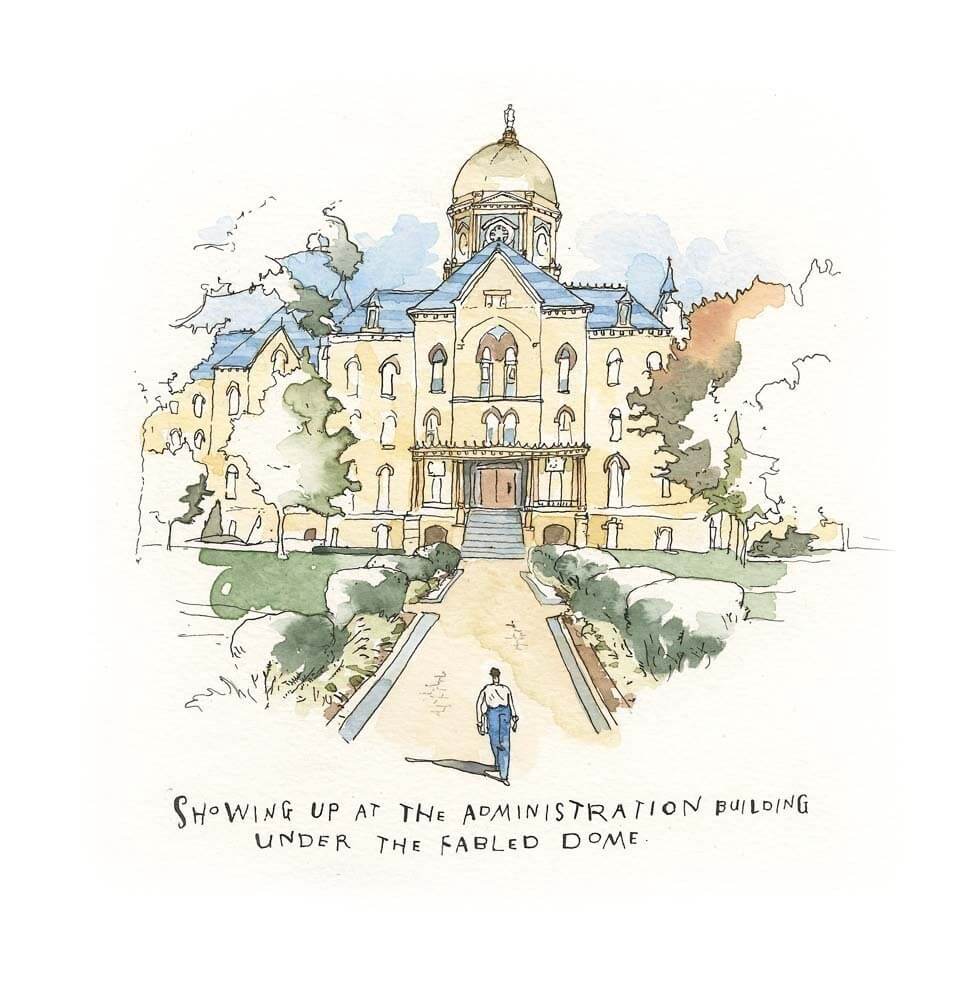

When I showed up at the administration building under the fabled Golden Dome, I was introduced to a man whose name I remember to this day but won’t reveal, as it would be un-Christian or just plain mean. I explained my predicament and assured him that I would pay my tuition by the end of the semester. He looked at me with disdain and said, “If you can’t afford to be at Notre Dame, you shouldn’t be at Notre Dame.” Huh!? I was to be thrown out so close to graduation? I was humiliated and angry. I went looking for Father Hesburgh.

I believed that the kindly president of the University would be appalled. He wasn’t available. I returned to my jail cell, pondering what to do next. To this day, I don’t recall how the situation was resolved. One of the other priests may have stepped in. In any event, I was eventually able to pay. Then, suddenly, school ended, my home was no longer a jail cell, and against all odds, I was a graduate of the University of Notre Dame, Class of 1960.

Postscript

So, what did I learn, battling to earn a degree from Notre Dame?

I learned from Milton and Shakespeare, Yeats and Steinbeck, and from my engaged professors about the beauty of the written word as it illuminates the depths of human behavior. I learned the best and worst of what humans are capable of in my history classes. I learned the complexity of God and the profound importance of free will in my theology classes.

Most importantly, I learned lessons that have informed my life ever since. That “hard” has its benefits. That will makes the difference. That one never knows from observing the outside what is going on in the inside. That one’s situation that seems permanent today isn’t necessarily permanent at all. Perhaps most of all, I learned what’s worth fighting for.

My fight after graduation was first to help my parents and siblings and their children when times got tough. Then my own family, children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren. I fought for peace and justice during the five years I was a member of the Peace Corps in Africa. My sons and I formed a charity that supports a home for sexually abused girls in the slums of Lima, Peru. A few years ago, when the bishop of El Paso, Texas, asked for help from former Peace Corp members to minister to the needs of migrants overwhelming the Church’s facilities, I spent some weeks at a parish center making sandwiches, mopping floors and running a van taking scared families to the local bus station, offering as much grace as I could.

I haven’t won every fight, but the joy of trying has been satisfaction enough.

Sean Sullivan’s newspaper career included a stint at The Wall Street Journal before he took his writing talents into corporate public relations and the launch of his own marketing communications firm. He lives in Naples, Florida, and when his granddaughter applied to Notre Dame last fall, he got to thinking. . . .